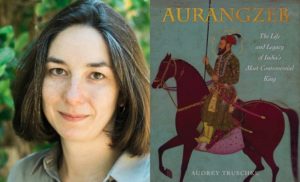

“Aurangzeb:The life and legacy of India’s most controversial king ,” written by Historian Audrey Truschke takes a fresh look at the controversial Mughal emperor. Truschke, an assistant professor of South Asian history at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey and an avid follower of Mughal history, attempted to undo the demonization of the Mughal emperor by people on social media. Twitter trolls and users have accused her of “white-washing” history, misleading readers and trying to cause unrest in India.

A Mellon postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Religious Studies at Stanford University, she is currently researching Sanskrit literary histories of Indo-Islamic political events. Truschke disapproves of efforts to replace history with mythology. “The RSS knows that the complexities of India’s past threaten to undermine their claims of a Hindu Rashtra…. In this project, ignorance is a friend to the RSS and dispassionate history coupled with critical thinking an enemy,” she says.

Truschke argues that the popular belief in mass conversion or killing of Hindus during Aurangzeb’s reign lacks historical evidence. The number of temples razed by him was in dozens — and not in thousands — as popularly claimed. Her portrayal shows how Aurangzeb also protected many Hindu and Jain temples and increased the Hindu share in the Mughal nobility.

Rather than hatred of Hindus driving his decisions, Truschke says, more likely Aurangzeb was guided by political reprisals and other practical considerations of the rule. “It is straightforward to condemn Aurangzeb, or any other pre-modern king when using modern, democratic, egalitarian norms.”

The commonly-believed worst aspects of Aurangzeb are exaggerated in modern imaginations of the Mughals. For example, Aurangzeb reinstituted the jizya, a discriminatory tax, but did not always enforce its collection. He destroyed some Hindu and Jain temples rather than thousands as many people believe and Aurangzeb killed many Hindus during his expansion wars but then he killed many Muslims as well and did not seem to discriminate by religion. This was cited in the works of Richard Eaton, a leading authority on the subject. According to Eaton, some confirmed destructions during Aurangzeb’s rule was over a dozen, with fewer tied to the emperor’s direct commands.

Aurangzeb ordered Vishvanatha temple in Benares, and Mathura’s Keshava Deva demolished in 1669 and 1670 respectively, to punish political missteps by temple associates and ensure future submissions to the Mughal state.

Acting on the premise that religious images held political power and Hindu kings targeted one another’s temples beginning of the seventh century, regularly defiling images of Durga, Vishnu, Ganesha and other deities. They periodically destroyed each other’s temples and commissioned Sanskrit poetry to celebrate and memorialize such actions. The Muslim rulers of India like Aurangzeb followed suit in considering Hindu temples legitimate targets for punitive state action.

The approach that Aurangzeb was a religious tyrant in contrast to “heterodox Muslim” figures like Akbar and Dara Shukoh who absorbed many Hindu ideas and thus became sufficiently “Indian” to be an acceptable ruler of India, according to Truschke is futile. He is maligned for demolishing the culture of tolerance built by Akbar, the third Mughal ruler and the great-grandfather of Aurangzeb and snatching the throne out from under Dara Shukoh, his elder brother. According to Truschke, Aurangzeb’s sectarianism was purportedly counterbalanced by the syncretic legacy of exemplary Indian Muslims. This thinking is shared by likes of V.D. Savarkar, an early ideologue of Hindu nationalism.

Both Akbar and Dara Shukoh, like Aurangzeb were more complicated than their popular reputations suggest. By holding Akbar and Dara Shukoh to balance Aurangzeb, we fail to learn much about these men and bind ourselves to ranking Mughal kings according to their purported Muslimness. Truschke feels it is unfair to have Aurangzeb reduced to his faith; rather he should be honestly evaluated to reclaim his fuller picture as a prince and an emperor. Misinformation and dubious claims by Aurangzeb’s detractors would fail to fulfill the core guidelines to history; understanding historical figures in their terms. Aurangzeb was an Indian emperor who strove throughout his life to preserve and expand the Mughal Empire, gain political power and rule with justice.

The notion that he killed or drove away his brothers mercilessly is another argument used by his detractors about Aurangzeb’s ruthlessness. Here again, one has to take into consideration the environment and culture at the time. The Mughals inherited a Central Asian custom that all male family members had same claims to political power. In such a custom, Aurangzeb had to compete with his other brothers to claim the Peacock throne. All brothers contested fiercely and at last Aurangzeb outmaneuvered all of them and mercilessly handled matters to assure flawless administration of his rule.

Truschke said that her project was not to play “political football “with Aurangzeb but to recapture the world of the sixth Mughal emperor operating according to entirely different norms and ideas. Despite animosity towards India’s Muslim rulers, India even today boasts of at least 177 towns and villages that carry Aurangzeb’s name out of a total of 704 such places that carry the names of the first six Mughal emperors in some form, the Indian Express newspaper said in a May 2016 report based on 2011 Census data. The share of Akbar is the largest — 251.

Lallanji Gopal, director of the Center for Advanced Study of Philosophy of India, notes in an essay in the book, “Ananya: A Portrait of India,” that the period of Islamic rule in India has been much wronged. “When presented in dark colors of persecution and intolerance, it made the excesses of British colonial rule appear comparatively mild. It suited the interests of the foreign ruling power to project the image of the two major communities in India as perpetually fighting,” Gopal wrote in the book published to mark India’s 50th anniversary of Independence.

“The British also benefited from encouraging religious division in Indian society, a tactic that the current Indian government has adopted,” she said. “The BJP and affiliated parties did not invent maligning Aurangzeb; rather, they are effectively parroting and amplifying the blueprint bequeathed to them by their former British masters,” she said. Noting that Aurangzeb is alive in India in public debates, national politics, and people’s imaginations, she earlier wrote in Stanford University Press blog: “Aurangzeb is controversial not so much because of India’s past but rather because of India’s present.”

Criticism of Truschke’s book is plenty. The social media is abuzz with one-second quips mainly accusing her “white-washing” history of misleading the readers. Aseem Shukla, co-founder, and a member of the board of directors of the Hindu American Foundation commented Truschke is not the first to minimize the evil that Aurangzeb personified. Romila Thapar, Ram Punyani, D. N. Jha and many other historians have also minimized Mughal tyrants’ evil.

Truschke could have elaborated further about the Hindu bureaucrats in Aurangzeb’s reign. Three leading lights of his court, Raja Raghunatha, Chandar Bhan Brahman and Bhimsen Saxena, are part of her narrative but without the attention they deserve. Although the biography successfully recovers the Mughal emperor for the contemporary readers, it would have helped to flesh them out further since most of them were not merely officials but scholars in their own right.

Babar and Aurangzeb are the two most controversial figures in the Indian history. Some RSS Muslim members think “Mughal ruler Babar was a Mongol. He was an invader who along with his general Mir Baqi unleashed atrocities on the people. Babar had hit the Ram Roop (incarnation) of Khuda. Babar did not know Islam. Baqi too grossly violated the tenets of Islam.” Babar and Aurangzeb Truschke argues that Aurangzeb followed Islamic law in granting protection to non-Muslim religious leaders and institutions. “Indo-Muslim rulers had counted Hindus as dhimmis, a protected class under Islamic law, since the eighth century, and Hindus were thus entitled to certain rights and state defenses. The ideas of a democratic institution did not exist at the time. Therefore, everything has to be justified regarding conditions existing in the world then. We should not try to balance it with the norms that exist today.

The main contention of the Twitter users is that Truschke has inaccurately portrayed the history of India in an attempt to glorify Aurangzeb. Some have even gone to the extent of judging the quality of her work by her nationality (she is an American) and called her the “future Wendy Doniger” and “future Romila Thapar.”

Audrey Truschke has countered these allegations by quoting her sources and urging critics to read her book. In one interaction, she also said, “Count me out for that project. Aurangzeb was no saint, and I have no interest in glorifying him.” In those cases where people have demanded to know who is funding her book to understand her intentions behind writing it, Truschke has said, “I have repeated this ad nauseam — all funding sources are listed on my CV, which is publicly available. All scholars do this.”

The hatred for Aurangzeb also comes through in his denunciation by the Shiv Sena and other groups that admire his arch-rival, the Maratha warrior, Shivaji. In 2004, a biography of Shivaji by James Laine was banned in Maharashtra because it had dared to raise questions deemed unseemly by his fans. In 2015, a Shiv Sena MP abused an officer on duty on camera by calling him “Aurangzeb ki aulad” (a descendant of Aurangzeb), after he razed some temples during a demolition drive sanctioned by the district collector in Aurangabad, based on high court orders. The reasons for the hatred for Aurangzeb are rooted and documented in the past. And admiration for Shivaji is not a recent 21st-century phenomenon!

Some quotes from well-known leaders on Aurangzeb:

The last of the so-called ‘Grand Mughals,’ Aurungzeb, tried to put back the clock, and in this attempt stopped it and broke it up: Jawaharlal Nehru.

Seeds of Partition were sown when Aurangzeb triumphed over [his brother] Dara Shikoh: Shahid Nadeem, Pakistani playwright.

Aurangzeb presided over a conquest state where Hindus had to submit to his rule most unwillingly: Muhammad Ali Jinnah.