Monia Acciari, De Montfort University 15/2/2018

Bollywood saga Padmaavat has divided India. The film, by the popular director Sanjay Leela Bhansali – whose epic (and controversial) love stories have earned him popular acclaim in the past – has provoked riots, attacks on cinemas and death threats against the film’s stars. The Hindu nationalist BJP announced a reward of nearly US$1.5m (£1.3m) for anyone who beheaded Bhansali and lead actress Deepika Padukone. Karni Sena, a pressure group representing the high Rajput caste, allegedly threatened to cut off Padukone’s nose.

Padmaavat tells the story of Padmavati, a 14th-century Hindu queen belonging to the Rajput caste and the Muslim ruler Alauddin Khilji. Such was the fury unleashed by the release of the film in January that some states banned its screening until the Supreme Court ruled that the bans were unconstitutional as they denied free speech.

Padmaavat is merely the latest of a string of films released in India over the past few years that have provoked unrest. What these films have had in common is their strong female characters. For example, Fire, directed by Deepa Mehta in 1996, depicted the provocative homosexual relationship between two women and angered the (mainly female) supporters of far-right political party Shiv Sena. Protesters stormed cinema theatres in Mumbai, burned posters and shouted angry slogans.

Lipstick Under My Burkha was also initially banned in 2017. The film, directed by Alankrita Shrivastava, portrays the intimate lives of four women. India’s Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) ruled that there was too much “abusive language” and “audio pornography” which might offend Indian Muslims. “The story is lady-oriented, their fantasy above life,” said a letter from the board of censors to the film’s producers. The decision was subsequently overturned on appeal.

Historically in Bollywood films, women have represented ideas of acceptability, motherhood and – in a complex way – nationhood to the audience. In doing so, they have been carriers of messages revolving around traditions and honour, which had not only to pass muster with the rigorous CBFC but also – and perhaps more importantly – be acceptable to the various religious and political communities.

Stuff of legend

The story of Padmaavat goes back to a ballad by the Sufi composer Malik Muhammad Jayasi in 1590 – which is when the figure of Padmavati seems to have emerged (although whether or not she really lived or is a character of folkore remains uncertain). It is a fascinating story, which has been adapted by several authors who have reinterpreted the Persian script and stitched elements of pride, honour and, territorial and cultural belongingness on to Padmavati’s character.

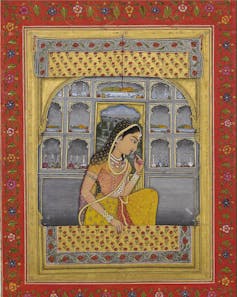

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

A simplified version of the story goes like this: Padmavati, a princess of unsurpassed beauty and virtue, is said to have committed “jauhar” – ritual self-immolation – rather than submit to the advances of the sultan, Allaudin Khilji, a Muslim. Allaudin had besieged Chittorgarh and killed her husband, the Rajput king, Maharawal Ratan Singh.

But Padmavati’s story has multiple, conflicting versions – often preserved by oral transmission and multiple traditions. The fictionalisation of Padmaavat has raised controversy and indignation among political and religious groups who have criticised and heavily condemned both the amorous story between a Muslim sultan and a Hindu queen (albeit the tension in those times was more about territorial dominance than religion) and damaged Rajput pride.

Passing judgement

The CBFC delayed the release of the film reportedly on the grounds of an incomplete application form submitted by the filmmakers. The board also questioned whether the film was fictional or based on historical facts. However, while the CBFC, as official censor, plays the role of passing judgement on the content of a film and how it is presented, much of Padmaavat’s controversy – like some of its predecessors – is about how it is viewed by various different sections of Indian society.

There are several points that can be made about the way these protests have unfolded – at the core of them, a secular tension between tradition and modernity. The first is about censorship in India. The CBFC is notoriously hard to please. But more important than the CBFC is another (unofficial) censor – the Indian public themselves. And what makes the public so hard to please is that pretty much any traditional story will offend one section of society while boosting the political self-confidence of another. And, as we have seen, these protests have a tendency to be pretty strident.

![]() And with Padmavaat we are not dealing with a straightforward historical epic, but a story which means different things to all the different groups. So while we don’t even know whether Padmavati actually existed, this account of her life – as stirring and beautiful as Bhansali has brought it to life on screen – is still churning up deep and violent passions. One thing’s for certain: it’s not easy being a film director in India.

And with Padmavaat we are not dealing with a straightforward historical epic, but a story which means different things to all the different groups. So while we don’t even know whether Padmavati actually existed, this account of her life – as stirring and beautiful as Bhansali has brought it to life on screen – is still churning up deep and violent passions. One thing’s for certain: it’s not easy being a film director in India.

Monia Acciari, Lecturer in Cinema and Television History, De Montfort University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.