The Supreme Court of India, some time ago, appointed a three-member Commission led by Justice Santosh Hegde to look into the problem of extrajudicial executions in Manipur. The Commission did not include a single woman despite the fact that violence against women by the state machinery is a significant problem in Manipur.

The “Extrajudicial Execution Victim Families (EEVFAM) Association, Manipur” which went to the Supreme Court in this connection is led by a woman, Neena Ningombam. The EEVFAM seeks justice for the innocent people killed in extrajudicial executions by security forces including Assam Rifles (AR) who enjoy immunity under the AFSPA [Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act]. This organization of widows and mothers of those killed by the security forces, demanded an independent probe into 1528 cases of extrajudicial executions by the security forces in Manipur (North East Sun, November 15, 2012).

The memorandum in this regard stated that 1528 people including 31 women and 98 children had been killed in fake encounters by the security forces between 1979 and May 2012. The figure included many women and children.

In 2009, the political situation in Manipur became explosive following a fake gun battle and extrajudicial killings by the Manipur Police Commandos of two innocent persons—the pregnant woman Rabina Devi (23) and Sanjit Meitei (25) in Imphal capital of the state.

A fact-finding team of civil and human rights activists, including this writer, visited the state shortly after and reported on human rights violations in Manipur. The team met with a group of concerned senior citizens who blamed the central government for its inaction.

The fact-finding team met and interacted with the families of those killed in the July 2009 fake encounters by the state police commandos. Many harrowing tales were narrated. Women whose husbands/sole breadwinners were killed narrated their woes in the absence of their husbands, whose earnings were the only support of their families and which were now starving. They demanded justice as well as income-earning opportunities to support themselves and their children. The DGP informed the visiting team that about 260 people had been executed by the police since January 2006 as they were “underground militants/activists”. The chief minister informed the team that the repeal of the AFSPA was a matter for the central government.

The team met the heroic Irom Sharmila Chanu, then in the tenth year of her fast demanding repeal of the AFSPA. It called upon the government to provide similar access to other civil society members. Her family members should be permitted to meet her on a regular basis.

Many of the killings in the state were “fake encounters”, that is, killings of the innocents in custody or otherwise, but without legal sanction. Each of these cases needed transparent investigation and punishment of the guilty. Further, there were many charges on the use of preventive detention laws to curb citizens’ democratic rights to protest and freely express their views.

It was noticed that i) Manipur, with a population of less than three million, had too many military, paramilitary forces (about 60,000) and too few civilian police force (about 5000). The basic purpose of policing, namely service delivery to the public, was downgraded at the cost of maintenance of public order; ii) the number of cases registered per year (including normal crime and extraordinary crime) was not large and the rate of conviction was poor.

The long conflict

The armed conflict between the Indian state and non-state actors in Manipur has been a long-standing affair. The Indian state tends to view the conflict as “internal disturbances”, which justified the large-scale deployment of armed forces and central paramilitary police forces and the imposition of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act 1958.

The AFSPA has been in force in Manipur since September 1980. However, following the fake encounter killing of Thangjam Manorama in July 2004, some municipal areas of Imphal had been freed from the operation of the Act. The place of occurrence of the incidents on July 23, 2009 was excluded from the operation of the Act. Further, Manipur Police Commandos are not protected under the provisions of the AFSPA.

The Act provides wide powers to the armed forces of the Indian Union, including the power to shoot on suspicion in an area declared as a “disturbed area” under its provisions. No legal action can be initiated against the armed forces for misusing the law without the prior approval of the Government of India.

With the prolonged imposition of the Act, the cycle of violence has spread geographically and in intensity. Enforced disappearances, arbitrary executions, torture, rape, housebreak, loot, arbitrary detention, etc have become everyday features of life in Manipur. And yet, few perpetrators of these gross violations of human rights were ever prosecuted. Thus, the armed forces enjoy complete impunity and immunity under the Act.

Many of the militant groups have factions difficult to distinguish from one another. Their brand of revolution based on extortion, kidnapping for ransom, kangaroo courts and summary executions, bomb blasts and terror tactics had led to increasing discontent among the general public directed at non-state actors too.

The previously vocal civil society organizations were immobilized by the state government with charges of siding with the banned organizations. This situation gave unofficial sanction for the elimination of any suspect and a killing spree by the police. In 2008 alone, the state witnessed the killing of more than 285 “suspects” by the security forces. Many of these cases remained unexplained.

Families of victims or eyewitnesses said that the deceased “suspects” were first arrested, taken to another place and then brutally murdered. Thus, domestic laws and international human rights standards were routinely flouted by state agencies. Respect for the law on conflict and the basic tenets of international humanitarian law were ignored by both state agencies and non-state ones.

Independent kingdom

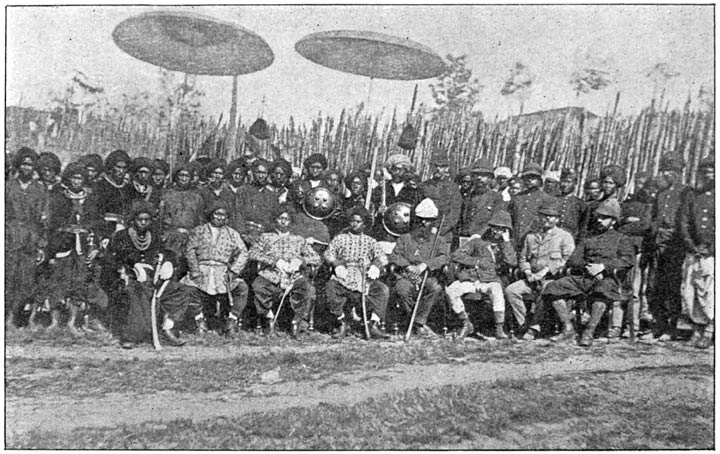

Manipur was an independent kingdom before the British took over the state in 1891. Manipuris are ethnically and culturally distinct from the people of mainland India and are more akin to the peoples in South East Asia. The British conquest of Manipur in 1891 was preceded by stiff resistance. The first Kuki armed resistance against the colonial power broke out in 1917. In 1939, a spontaneous resistance by women called the “Second Women’s War” or “Nupilal” was organized against exploitative trade practices by the Marwari traders in the export of rice to Myanmar. The traders enjoyed the support of the corrupt feudal elite and the king.

Manipur regained independence from the British in August 1947. A constitutional monarchy was established under the Manipur State Constitution Act 1947 and elections on the basis of universal adult franchise took place in 1948 and an elected state assembly was in place. The Maharaja, however, was forced to sign a controversial Manipur Merger Agreement with India. The elected legislative assembly was dissolved, and the council of ministers disbanded, followed by direct rule from Delhi. Manipur was made a union territory in 1963 and became an Indian state in 1972.

A fertile alluvial valley extends from north to south in the middle of Manipur, which is surrounded on all sides by hill ranges forming a part of the eastern Himalayas. Though it constitutes only about 12% of the total geographical area, the valley is populated by more than 75% of the total population of less than three million.

Among the Manipuris, the Meiteis form the largest ethnic group traditionally inhabiting the fertile valley region. The surrounding hill ranges are settled by many hill tribes, mainly the Nagas and the Kukis with many subgroups within each. While the Meiteis thrive on wet cultivation, the tribal population subsists largely on slash-and-burn cultivation and relies heavily on the valley for basic needs.

An underground movement for independence began in 1964 with the founding of the United National Liberation Front (UNLF). Other militant outfits followed in the late 1970s: primarily, the Revolutionary People’s Front and its armed wing the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), 1978; People’s Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak (PREPAK), 1977; Kangleipak (original name of the state) Communist Party (KCP), 1980; and the Kanglei Yaol Kanna Lup (KYKL), 1994.

In the Hills, there are Naga underground militant outfits: National Socialist Council of Nagaland (Isak-Muivah); National Socialist Council of Nagaland (Khaplang); and Kuki outfits such as the Kuki National Organization and its armed wing Kuki National Army (KNA); Kuki National Front (KNF); Kuki Revolutionary Army (KRA); Kuki Liberation Organization and its armed wing the Kuki Liberation Army (KLA) and others.

The tremors of the movement for independence in neighboring Nagaland spread to the Naga-inhabited districts of Senapati and Ukhrul in Manipur. As the state forces failed to contain the movement, the army was called in. To facilitate army operations, a legal framework was introduced in the shape of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act 1958.

The Act is a direct descendant of the Armed Forces Special Powers Ordinance 1942 used by the British during the Second World War to suppress the Indian freedom struggle. The present Act is more draconian but applicable only in distinct geographical regions declared “disturbed areas” under the Act. Initially, parts of Manipur were declared “disturbed areas” but in 1980 the whole state was declared a “disturbed area” under the Act of 1958.

An international human rights agency in 2008 documented the failure of justice in Manipur under the AFSPA. The agency noted that “security forces are bypassing the law and killing people on suspicion that they are militants instead of bringing them before a judge. In the name of national security and armed forces morale, the state protects abusers and leaves Manipuris with no remedy to secure justice.”

Though the operation of the Act was eventually withdrawn from the Imphal municipal area, the state police commandos operating along with paramilitary forces have continued killing suspects taking advantage of the immunity provided to the central armed forces.

Focusing only on the so-called “encounters” between state forces and suspected and banned underground militant groups in 2008, the emerging pattern is one of escalation in the number of questionable killings in the state. Some distinctive features in the so-called police encounter killings are: isolated locations; absence of casualties on the part of the security forces; recovery of 9 mm pistol or hand grenades in most cases; combination of force from the police commando units and central security forces including AR; the slain victim being taken away from home and killed at another place; theft of money, mobile phones and other valuables from the victims; and so on.

In most of these cases, the local “meira paibis” (women torch bearers) and villagers in the vicinity of the place of occurrence said that either the victims were brought there and killed or were already dead and dumped there after firing some shots in the air. There are many instances of protest by the local inhabitants against bringing and shooting of detainees at such spots, and also of confrontations with the security forces over these incidents.

Irom Sharmila, who has been on a Gandhian indefinite hunger strike for over a decade demanding the repeal of the AFSPA, has been kept alive through forcible nasal feeding. She is facing a charge of attempted suicide under the colonial Indian Penal Code.

Degeneration of forces

Case studies in 2008 showed that the security forces involved in many instances are combined teams of the Manipur Police Commandos and either army or paramilitary forces such as the Assam Rifles set up by the British in 1835. After independence in 1947, the colonial Assam Rifles has become a historical anomaly. It is redundant since considerable state police forces have come in the period after 1972 when they were set up as independent state governments of the Indian Union.

Under the AFSPA, the central armed forces and paramilitary units are immune from penalty for their acts. But this sense of not having to answer for their actions has percolated down to the state forces as well to such an extent that the Manipur Police Commandos freely kill people on their own without fearing consequences. Instituted for the purpose of containing insurgency in the state, the Manipur Police Commandos have digressed from their original purpose to embark on a path of seeking to fulfill personal agendas.

A former advisor to the Governor of Manipur states: “In Manipur, civil policemen and officers were selected and trained as commandos. Although they did a good job initially, they soon deteriorated into a state terrorist force due to faulty leadership. They started extorting money from the business community, picking a leaf out of the insurgents’ book. What were the consequences for the hapless public? Here were five to six underground groups extorting money from the traders and here was a special wing of the police force, set up to arrest the underground, who also demanded their share of the extortion pool.”

Indeed, the number of killings of “suspects” by the police is even considered an achievement and the perpetrators are rewarded with cash incentives, medals and gallantry awards by the state government which ultimately serves as a stepping stone to promotion. The impudence of the state government in doling out such incentives and awards to the perpetrators of such atrocities fuels the security forces further into even more blatant killings.

In many cases studied in 2008, independent reports claim that the places of occurrence of the “encounters” were different from the ones claimed by the police. It often transpires that the victims were picked up from their homes or from their locality by the security forces followed by police claims that they were killed in encounters. In one case, the leaders of 19 villages in and around New Keithelmanbi area held a public meeting to protest against the “fake encounters” in the area claiming all encounters within the said area were fake.

Another issue of significance is the recovery of large sums of money from the person of the victim. Family members often say that the victim left home with a substantial sum of money, which is not reflected in the recovery memos of the police. Recoveries of incriminating pistols and grenades are almost always made in the aftermath of alleged encounters but recoveries of sums of money are seldom recorded. Genuine concerns thus arise as to whether the financial aspect played a vital role in the killing of the victims. The situation has come to such a pass that people of the state feel extremely insecure in carrying large amounts of cash on their persons, even for personal or business purposes.

Recruitment issues

The recruitment of personnel for the Manipur police department is a big issue. A large number of police personnel are recruited frequently. The recruitment processes are conducted with a semblance of transparency but always reek of large scale corruption. Once the initial hurdle of selection and appointment has been overcome by a candidate, the clamor for the coveted place of posting in the state commando units begins, as these units offer useful avenues for making money by various methods including “encounter” killings of suspected militants, which can earn the commando recognition and rewards, cash incentives, medals and gallantry awards.

In other words, gaining recognition for “devotion and dedication” to duty is more expeditious for the commando unit than the ordinary police force. As a result, a paradigm shift has occurred in the mode of operation of the police commando units contrary to the purpose for which they were set up. The police commandos are more concerned with the achievement of their personal agendas than with the main objective of maintaining public order and security of the state, thereby straying from their primary objectives.

For one example, on July 12, 2008 the state security forces abducted one Ziaur Rahman Shah, the son of the chief engineer of the minor irrigation department, along with his two friends, confiscated their belongings including a laptop, three mobile phones, and money amounting to Rs 14,600, and released them after they promised to pay a ransom of Rs 300,000. Thus Ziaur Rahman and his friends lived to tell their tale. The situation today is such that people are being eliminated not only for possessing substantial amounts of money but even for paltry sums.

A further aspect that requires serious consideration is the “relief” usually proffered to the families of victims. Though the state government usually skirts the payment of compensation to most of the families by labeling the victims members of a proscribed outfit, the few who do obtain such compensation are compelled to be content with insignificant sums doled out to them since such families are normally poverty stricken.

Numerous fact-finding commissions have been instituted to inquire into controversial incidents in the past. However, in no case has the findings of such commissions been revealed to the public, nor the errant personnel punished. The findings of such inquiries are eventually shelved. Though in some cases departmental inquiries are launched, these rarely reach a conclusion.

Another disturbing trend, especially among the tribal population in the Hill areas, is the appeasement measure usually undertaken by the security forces to subdue the hue and cry following the extrajudicial killing of an individual by resorting to the prevailing local custom of “mankad”. According to this local custom, whenever someone violates the custom and tradition of a particular tribal community, “mankad” allows the “wrong” to be “righted” by offering an elaborate feast to the members of the offended village by the offending party along with a negotiated sum of money proffered as compensation.

In this way, any semblance of protest against such atrocities is silenced. Over and above the rampant instances of extrajudicial killings in the state, cases of arbitrary detention and torture are routine. In almost all these cases of detention, denial seems to be the key word of the security forces. The claims of the victims are silenced with fear of reprisals or they keep persisting with their own versions and any protests or agitations are left unattended by the authorities to be forgotten in due course of time.

The demand of the people to repeal the draconian laws and the recommendations of international bodies to review and repeal AFSPA and the failure of the Indian government to take any action on the recommendation of the Jeevan Reddy Committee to repeal AFSPA has elicited the comment: “The Indian government has not only ignored the pleas of ordinary Manipuris and UN human rights bodies to repeal the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, but has even ignored the findings of its own committee. This reflects the sort of callousness that breeds anger, hate and further violence.”

The armed conflict in Manipur has officially been viewed as largely a matter of “internal disturbances”, justifying the large-scale deployment of Assam Rifles and other central armed police forces along with the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act 1958. The prolonged imposition of the Act to contain the violence has had the opposite effect of strengthening the cycle of violence.

The armed militants indulge in a “revolution” based on extortion, kidnapping for ransom, kangaroo courts and summary executions, bomb blasts and terror tactics, opposed by the general public. The vocal sections of civil society are silenced with charges of alignment with banned organizations. Unofficial sanction is provided to elimination of suspects.

The jury’s opinions

An Independent People’s Tribunal (IPT) met at Imphal in 2009 to take stock of the role of the Manipur Human Rights Commission (MHRC) on violation of human rights in the state and the operation of the draconian AFSPA 1958.

The jury said:

- Manipur is especially unsafe for women. Protective laws do exist but ordinary people are not aware of their provisions. A legal literacy program, as in Kerala, must be executed through the Panchayats, schools and colleges both by the NGOs and the government. If the police do not record complaints there is a provision in law for filing private complaints but for this legal assistance is necessary. A group of lawyers must be organized to assist the people.

- The immunity provisions under Section 6 of the AFSPA are not applicable in seven assembly constituency areas of Imphal city from which the application of the law has been done away with in 2004 after the case of the rape and murder of Thangjam Manorama by the Assam Rifles men (2004). Legal immunity is thus not available to those officers who violate human rights in this area. However, in many cases the victims were taken away from here and the violations took place in other areas where the Act was in force.

- The MHRC does not have powers to issue any legally binding orders. It can only give recommendations for action which are not binding and can be ignored by those in authority. The powers of the MHRC must be enhanced.

- The Act was operative only in Manipur when it came into existence in 1958. Its operation was extended to the other six states of the northeast in 1987 via an amendment. While ex-gratia payments have been made to the families of victims, no action has been taken against the offending security personnel. Without any reason some boys are taken away and killed. Sometimes women too are killed. Some joint action committees are formed locally who go to the chief minister and he makes some ex-gratia payments. He doesn’t ensure legal action against those who have committed murder. One hundred thousand rupees is prescribed as the price of an extinguished life!

- The Act mentions only the armed forces but not the police who have some responsibilities when a rape or murder takes place. The Guwahati High Court has said that arrest comes first and then the extrajudicial execution. When an arrest is made the arrested person must be produced before the local police authority. The Supreme Court of India in 1997 has issued detailed guidelines to be followed when making arrests. In 1991, the Guwahati High Court issued orders that the army is bound to hand over the arrested persons to the local police. In our country there are laws, statutory laws, constitutional laws and judicial laws which must be obeyed. The Act cannot overthrow Supreme Court guidelines.

- There should be a mechanism for periodic review of the law as ordered by the Indian Supreme Court in 1998 in the case filed by the Naga People’s Movement for Human Rights. Manipur is very much part of India and people’s sentiments must be respected.

- Simply because there is a provision for arresting somebody, it does not mean that he can be killed. In Manipur arrest has always been for the purpose of eliminating the arrested person.

- Affected people are not being allowed to file FIRs (First Information Reports) using various methods and by giving ex-gratia payments by local MLAs, chief ministers and others.

- We do not have accounts from military authorities (including Assam Rifles) on the incidents but have reports from others in civil society. Military authorities must be asked to give their versions.

- State police forces often use the phrase “combined forces” of army and civil police to take advantage of the provisions of Section 6 of the Act, which provides impunity to the armed forces in such cases.

- In cases where FIRs are filed by the police, the police cannot refuse to take FIRs from the public. Cross cases can be filed giving different versions from the police versions. The right to life and rule of law will be affected if ex-gratia payments are accepted by the families of victims. In one case the victim family refused to accept ex-gratia payment and asked for legal investigation of the case.

- Army troops believe that militants are separatists and can be killed. Ruling political parties believe that they cannot rule without the support of the army and AFSPA. This is a failure of politics. In reality, the militants have increased their presence. Once Nagas were called “hostiles”, Mizos were “rebels”, and Manipuris were “insurgents”! Now, Manipuris are being called “extortionists” by the authorities. Cases involving the army are fewer now and cases involving the police are more.

The IPT looked into 40 fake encounter killings and gross violations of human rights and two cases of torture. The jury heard written and oral testimonies. The main points that emerged were:

- No notice of the sittings had been served on the government authorities or the police; therefore, neither the alleged perpetrators nor representatives of the government appeared before the Tribunal. In none of the cases were the copies of the FIR provided to the jury. No post-mortem reports were available. In some cases FIRs had been filed against the victims who are no more. %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

- Some of the perpetrators were troops from Assam Rifles; others were Manipur Police Commandos. In one case, it was the Rajputana Rifles. In still others, they were the combined action of the police commandos/army/Assam Rifles.

- In seven cases, the victims were called out of their houses; in 29 cases the victims were picked up from different places in the city. In almost all cases there were allegations of encounters with the security forces. In some there were reports of recovery of arms and ammunition from the site of the killing or from the persons killed. No details of criminal or political antecedents were provided except in a few cases.

- In one particular case, a 12-year-old school boy named Mohammed Azad Khan was dragged out of his house by a combined team of police commandos and 12 Assam Rifles troops. He was asked to run through the paddy field adjacent to his house. When he was running the perpetrators fired at him and killed him. The victim’s family was not allowed to file a police complaint. An enquiry was ordered by the state governor but no report of findings was submitted. The writ petition filed by the mother was pending in the Guwahati High Court. The victim’s uncle stated that when he wanted to file a police complaint the police commandos asked him to withdraw his complaint if he wanted to save his life. The chief minister along with the local MLA visited the victim’s family and paid them an amount of Rs.200,000. No further action was taken to proceed with the case.

* In another case, a patient of cervical spondylitis was pulled out of his house and taken to the police station. When the victim’s family went to the police station the next day they were told that their relative had been killed in an encounter. A case filed in the Guwahati High Court was totally denied by the state government. There was no reply from the central government to the appeal made by the victim’s family. There were several other similar cases of extreme atrocities by the police commandos and AR personnel.

- Special mention was made of the killings on July 23, 2009 of Chongtham Sanjit Meitei and Thockchom Rabina Devi. The IPT took note of the report published in Tehelka (Vol.6, Issue 31, August 8, 2009), which showed that Sanjit was taken by the Imphal district police commandos to a pharmacy by the side of the main road and later his body was brought out from the pharmacy. The photographs showed that Sanjit had not offered any resistance of the kind that could potentially justify any use of force against him. Rabina Devi, a pregnant woman, was standing by the side of the road along with her minor son and was about to buy a banana from the roadside vendor when she was killed in a police shootout. The photographs showed a bystander taking photos of the dead bodies of Sanjit and Rabina being loaded on a truck.

There was a prolonged state-wide agitation on the issue. The victims’ families filed complaints with the police and the High Court. The MHRC was asked not to start an enquiry into the incident by the state government which said they were making the enquiry. The Guwahati High Court asked the police to register a complaint on the basis of the complaint filed by Rabina Devi’s husband, but the DGP and the state government filed an appeal before the Division Bench. The matter was pending.

The IPT noted that the facts of the other cases submitted before them did not justify the extreme step of shooting people to death. The IPT concluded that unarmed people who were taken out of their homes at midnight or in daylight would not have indulged in encounters with the police/army resulting in their death. Such unfortunate victims included invalids.

The IPT observed that the circumstances of the cases clearly indicated that if effective machinery for investigation had been there, as it should be in a democratic state, there would not have been any difficulty in tracing the culprits. In cases in which persons had been taken into custody from or killed in public places, the police department and the investigative machinery were not doing their duty. That even the legal machinery was not allowed to function was clear from the case of Rabina Devi.

A common feature in these cases was the standard narrative by the army/police commandos that the victims were the first to open fire and that they were killed in the retaliatory fire of the security forces. But when the relatives received the dead bodies from the mortuary, they found marks of severe torture inflicted on them before they were shot dead. There was evidence that limbs were broken and twisted; necks were broken or slashed; soft flesh from the limbs slashed away; marks of injuries on the face or body; ventral side injuries with internal organs protruding outside; and, in one case, the mouth of the victim was stuffed with filth.

These injuries, clearly, were not the result of gunfights between the army/police commandos as claimed. Further, relatives found the dead bodies of victims with trousers and shirts not fitting their body structure. They were wearing different clothes when they were taken by the security forces. Camouflage clothes were put on their bodies after they were shot dead, it was alleged.

The MLAs and chief minister are part of a democratic government elected by the public. Hence it cannot be assumed that they were persuaded to pay ex-gratia payments to underground extremists killed by the security forces: they must have been at least prima facie satisfied that innocent people had suffered.

The IPT concluded that the root cause of extrajudicial killings lay in the provisions of the AFSPA, which gave unlimited powers of immunity to the armed forces. Section 3 empowered the governor of the state to declare an area as “disturbed area” where armed forces could be used to aid civil power; Section 4 gave very wide powers to the armed forces to arrest without warrant, enter and search any premises without warrant, make any arrest, open fire or use force even to the point of causing death to any person. The provision in Section 5 that the arrested person must be taken to the nearest police station was never followed. An order passed under Section 3 is not justiciable and the right to remedy is totally taken away by the protection given under Section 6.

The net effect was that even if the state government machinery was satisfied that power under the Act was exercised in excess, no action was possible against the perpetrators.

Piecemeal exclusion of an area from the operation of the Act was not sufficient. It is not difficult to fabricate stories of encounters outside the excluded areas even though as a matter of fact people were taken into custody in the excluded areas and killed. The IPT noted that in 14 cases, including that of Rabina Devi and Sanjit Meitei, the perpetrators were Manipur Police Commandos who are not covered under the AFSPA with immunity under Section 6. The ordinary law of the land governed them. The IPT called for a strong and effective state Human Rights Commission; the National Human Rights Commission had to get involved in the situation in Manipur; the National Legal Services Authority should take effective steps to spread legal literacy among the common people and make information available on how free legal aid can be obtained.

The final verdict of the IPT was that the concerned area of Manipur had witnessed instances of torture, extrajudicial execution and enforced disappearance of a number of people. Prima facie the excesses had been committed by the personnel of the army/Manipur Police Commandos. The state government cannot shirk its duty to investigate deeper into each of these incidents so as to protect the lives of innocent people. The presence of underground outfits in the area and their illegal activities cannot be used as a smokescreen for perpetrating human rights violations. The steps taken by some NGOs had been useful but the “ultimate redress is still far away.”

The IPT made a series of recommendations including: i) repeal of the AFSPA; ii) prevention of misuse of the provisions of special security legislations; iii) setting up of an independent Human Rights Commission in the state with no official interference in its functioning; iv) strict enforcement of procedural guidelines issued by the NHRC with regard to “encounters” and investigation of complaints by an independent agency; v) transparency of investigation in all such cases and public availability of all enquiry reports; vi) provision of prompt rehabilitation and interim relief; vii) withdrawal of paramilitary forces as far as possible and sensitization programs for such forces; viii) special attention to the Manipur situation by the NHRC; and ix) spreading legal literacy among the people of Manipur by the National Legal Services Authority.

Grave rights scenario

At the very least, the role of the Assam Rifles (AR) and the AFSPA in the Northeast has been controversial. The Union Home ministry maintains that the AR is the “oldest paramilitary force” under its control and provides increasingly large funds for it. If it is a police force under the Ministry as the other Central Armed Police Forces are, then it should be accountable to it, but it is not! Though characterized as a central paramilitary force in the annual reports of the MHA, it works under the operational control of the Army in the Northeast. This is an anomaly which needs rectification.

In view of the grave human rights scenario in the Northeast, the dual control of the AR by two central ministries is deleterious and works to the disadvantage of the people of Manipur. It would be better to deprive the AR of its internal security functions which should be taken care of by the substantial state police forces, which have grown in the Northeast in the recent period. AR must be deployed for border guarding duties only along with the BSF. The government of India’s Vision North East Region: 2020 document, formulated as part of its Look East Policy, appears clearly contradictory to the workings of the AR and AFSPA in the state. The contradiction must be removed to realize the real potential of the Vision.