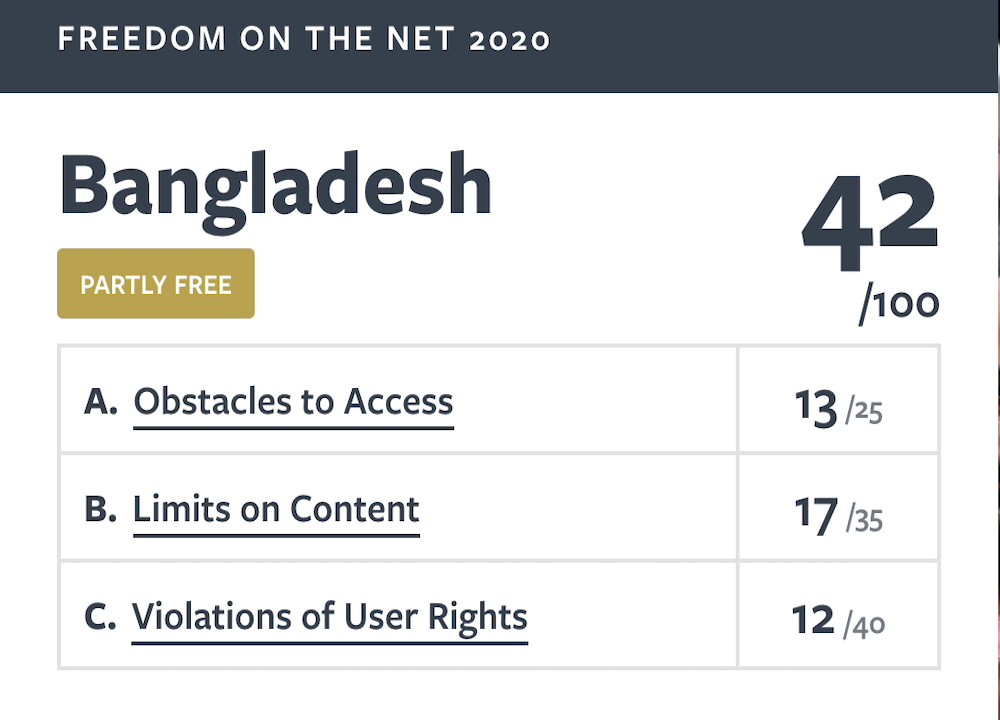

The Freedom House has published its set of 2020 country reports on online freedom around the world — and for anyone interested to read about the increasingly precipitous decline of online freedom in Bangladesh, this well researched report (which references Netra News’s articles on a number of occasions) is very well worth reading. We all know about the widespread prosecutions and arrests under the Digital Security Act , which the report refers to and criticises, but here are eight other aspects from the Freedom House survey worth emphasising.

- Democratic decline

The report’s overview presents a good summary of the democratic situation in Bangladesh

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the government ramped up its efforts to restrict the online space and suppress those criticizing the government’s response. Authorities blocked critical websites, enhanced targeted violence, and arrested journalists and users alike. New investigative reporting also shed light on the government’s capacity to manipulate content and deploy technical attacks.

The ruling Awami League (AL) party has consolidated political power through sustained harassment of the opposition and those perceived to be allied with it, as well as of critical media and voices in civil society. Corruption is a serious problem, and anticorruption efforts have been weakened by politicized enforcement. Due process guarantees are poorly upheld and security forces carry out a range of human rights abuses with near impunity.

2. The increasing growth of internet access is also reason why the government is increasingly concerned about controlling it

The report provides details on internet access in the country. Whilst in 2017, the Bangladesh government estimated that 15% of the population had access to the internet — as of March 2020, it has now grown to 61%. And of those who have access to the internet, 90% — over 95 million people — can now access it through their mobile phones.

Whilst the government is in principle supportive of internet access, it wants to reduce access to, or strictly control what can be accessed on, social media. So, in July 2020, the Bangladesh Telecommunications Regulatory Commission (BTRC) ordered service providers to stop providing free service to social media platforms. The report also stated that:

“The BTRC has tried to ramp up its technical ability to block, filter, and remove content online, including on social media. In September 2019, the BTRC confirmed that the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) set up the Cyber Threat Detection and Response (CTDR) project under the National Telecommunication Monitoring Center of the DoT. The system is reportedly intended to monitor websites, apparently for keywords, to then enable police to request that the BTRC remove or block “derogatory” or “harmful” content. The 1.5 billion takas ($17.6 million) designated for the project enables the monitoring of 2,700 Gbps of data. CTDR is also reportedly installing deep packet inspection (DPI) to enable blocking of any online content, including Facebook pages or accounts, more quickly.”

3. Regulators are not independent

This will come as no surprise to anyone, but whilst the report states that the BTRC is supposed to be “an independent regulatory body responsible for overseeing telecommunications and any related ICT issues” it concludes that:

“in practice the body lacks independence and represents the interests and priorities of the government.”

4. Blocking websites is common

The report concludes that: “the government continues to restrict access to websites carrying information critical of the government”. It states:

In December 2019, Netra News, a Sweden-based investigative journalism portal publishing both in English and Bangla languages, was blocked for an article alleging corruption against Obaidul Quader, the country’s minister of road transport and bridges and general secretary of the ruling Awami League. The article claimed he received luxury watches as gifts. According to the BTRC, the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (the intelligence agency of the military) ordered the website be blocked, although the agency declined to confirm this. The site remained unavailable as of July 2020.

Authorities also blocked websites during and because of the COVID-19 pandemic. In March 2020, Netra News published a leaked interagency United Nations memo that claimed the pandemic could result in up to 2 million deaths in Bangladesh if immediate steps were not taken. Following the report, a mirror site of Netra News available in Bangladesh was blocked. In April 2020, the government reportedly ordered the BTRC to block 50 websites for spreading misinformation about COVID-19. The English and Bengali versions of BenarNews, an online affiliate of Radio Free Asia that republished the Netra News report about the UN memo, were confirmed to be among the 50 sites blocked. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported that from May 7, 2020 to the end of the coverage period, BenarNews remained largely inaccessible, although it appeared that some internet protocol (IP) addresses or mobile towers may have been able to access the site on May 7.

In October 2019, the BTRC ordered the blocking of an online complaints page of the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology website, where students could file online complaints. Over 175 complaints were anonymously made by current and former students, many of which were about physical violence (sometimes fatal), intimidation, and abuse from senior students …

News outlets continued to be blocked temporarily. In April and May 2019, Bangla.report and Poriborton, two popular news sites, were blocked, and were available again as of May 2020. While no official explanations were provided for the blocks, some analysts suspect that they were targeted for publishing articles critical of the government. In March 2019, both Al Jazeera’s English website and the local news and discussion site Joban were temporarily blocked. Joban had published reports accusing the country’s top security adviser of using military intelligence officials to abduct three men involved in a business dispute with the official’s wife. The government denied responsibility for the blocking.

5. Authorities force publishers to remove content

The Authorities employ legal, administrative, and other means to force publishers to delete legitimate content. One example it gives is this one:

The editor of the news outlet Bangla.report alleged that the minister of post and telecommunication threatened to take legal action if the website did not remove an article about an individual who wanted to meet with the minister at a business summit. After declining to remove the content, the website was temporarily blocked.

6. Government disinformation on social media

Authorities are involved in disinformation which it deliberately circulates on social media. It quotes Netra News to support this contention:

Whistleblower reports published by Swedish investigative news site Netra News in May 2020 alleged that a unit under the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence — the Public Relations Monitoring Cell (PRMC) — has contracted civilians to maintain thousands of fraudulent Facebook pages and accounts. They reportedly receive daily directions outlining which pages and accounts to target, most often journalists, dissidents, and opposition figures. The report had not been confirmed by other sources.

7. Extralegal intimidation or physical violence in retribution for their online activities

The report concludes that:

Physical violence, intimidation, and harassment of online journalists and ordinary users have increased in recent years, particularly during political tense moments like protests and elections, or linked to the discussion of political topics online.

It includes the example of Abrar Fahad, a student of the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, who was tortured and murdered in October 2019 by members of the student wing of the ruling Awami League. It also refers to the fate of Saleh Uddin Sifat, a Dhaka University law student who was hospitalised and in critical condition after being being criticised for anti-government social media posts.

And of course it refers to the disappearance of the journalist Shafiqul Islam Kajol who was “disappeared” for 53 days.

8. Government hacking

Hacking is illegal — but seemingly not when the government does it. The report again refers to the Netra News article mentioned above which exposes how the government contracts a unit of hackers to gain access to the Facebook profiles and pages of activists, dissidents, and opposition figures. It states:

May 2020 reporting from the Swedish investigative Netra News cited whistleblowers alleging that the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI) maintains a team of civilian contracted hackers who work for the Signal Intelligence Bureau (SIB). The hacking team has sophisticated technology that gives them the ability to intercept SMS messages to access verification codes for two-factor authentication. Netra News also claims that they have evidence that the SIB hacked into the Facebook account of famous writer Pinaki Bhattacharya in September 2018 by intercepting the two-factor authentication passcodes. The whistleblower cited in the Netra News reports also alleged that the unit maintains a “collection of hacked accounts” that they use for high-value hacking operations.

According to the article, during a May Facebook Live event on COVID-19 and government censorship between the editor-in-chief of Netra News Tasneem Khalil and the student organization Swatantra Jote, members of the Public Relations Monitoring Cell (PRMC) mass reported the page to Facebook. The platform then imposed restrictions on Swatantra Jote’s page.