Daily Star; Bangladesh May 12, 2018

Inam Ahmed and Shakhawat Liton

It’s called crazy medicine. Produced in Myanmar, the dangerous drug very easily crosses the border and reaches cities, towns and villages of Bangladesh through various channels — sometimes in full knowledge of law enforcers. It now seems unstoppable and is poised to cripple the country’s biggest hope — the youth. Millions are now addicted to the pink pills. They take it as stimulant and end up with organ damage and mental derangement. The Daily Star has prepared a three-part series on the invasion of yaba and is running the first part today.

Those crazy pink pills were what everybody was talking about.

By 2010, they were fetching as high as Tk 1,200 per piece. The youths from teens to those in their 20s and 30s were the main consumers. They partied nights away under the influence of the drug, remained awake for nights together doing nothing; life for them had turned into high profane pottering around.

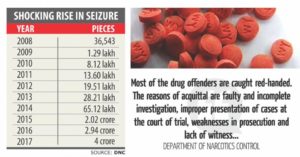

Nobody knew the total consumption of the drug. But the Department of Narcotics Control was seizing more and more yaba consignments every year. In 2006, they seized only 1, 687 pieces of the pills; the number went up to over 36,000 two years later and to over eight lakh pieces in 2010.

That gave the narcotics officials a rough guesstimate of the pervasiveness of yaba, because it is thought that only 10 percent of the drug could be captured and 90 percent flowed into the market. That was a huge figure.

No matter how much the anti-drug officials tried to control the trade, the invasion of yaba — the crazy pills as the Thai name meant — proved unstoppable. And there was only one source the pills were coming from –Myanmar.

Alarmed, they met their Myanmar counterpart in Yangon in 2011. Both sides saw the rising invasion of yaba and agreed to fight it together. Happy came back the Bangladesh team.

The same year, the catch crossed one million pieces; that meant at least 9 million pieces had reached the consumers. A year later, the catch jumped alarmingly to 2.1 million pieces. It was clear that Myanmar was not doing anything to stop Yaba.

So on October 27, 2013, the Department of Narcotics Control sent a list of 37 yaba factories inside Myanmar to its Yangon counterpart, the Central Committee for Drug Abuse Control, and urged it to take action.

Three months later the reply came from Myanmar. It was a small two-paragraph letter replete with grammatical errors, saying that they could not find the yaba factories because the spelling of the places did not match with any real location.

“Could you please put the location on the perspective map and send us back,” the letter said. The matter ended there as Bangladesh had no way of pinpointing the yaba factories on maps.

The yaba trade tripled the next year in 2014. Some 6.5 million pieces of the crazy pill were seized.

The year 2015 was a watershed in the explosion of meth the short for methamphetamine, the ingredient for yaba, and it seemed the druggies had by now switched from other drugs like Phensedyl and cannabis to yaba. That year over 20 million of the pills were seized.

The situation was alarming. Demographically Bangladesh is a young nation. Over 52 percent of its population falls in the age bracket of 15 to 35 and it is the same prime group that is now addicted to a deadly drug that can give them temporary happiness but in long run destroys the abusers both psychologically and physically. It causes anxiety and aggression and damages kidney, heart, liver and brain as well.

So Bangladesh sat with Myanmar again in May 2015 in Dhaka. Again the Myanmar team agreed to fight yaba. But they walked away without signing the joint minutes, leaving their promise all empty.

And so in the next two years, yaba trade doubled again with over 40 million pills seized in 2017.

So in April 2017, Border Guard Bangladesh met Myanmar Police Force in Dhaka with yaba smuggling on the table. Myanmar promised to work closely with BGB to fight yaba and went away with a list of spots on the border from where drugs are smuggled.

Again, there was no let up in the yaba flow. By now with the increase in supply, price had come down to between Tk 180 and Tk 200 a piece.

During Myanmar’s national security advisor U Thaung Tun’s call on Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in July 2017, she drew his attention to the issue of drug smuggling particularly yaba to Bangladesh from Myanmar. Tun, in response, assured Hasina of all sort of cooperation for eradicating drug smuggling.

Bangladesh once again sat with Myanmar in Yangon in August 2017. It was already clear that the only source of yaba was Myanmar. Bangladesh by now as a precautionary measure had banned import of pseudoephedrine; an ingredient used in cough syrup and can be turned into meth. There were reports of numerous yaba factories operating across the border with total impunity. International reports also strongly linked Myanmar to yaba trade.

Dhaka handed Yangon a list of 49 Yaba factories this time. The Myanmar team said they would “look into it” and went away leaving an unsigned and unpledged document lying on the table. Nothing has been heard about what it did with the list.

Bangladesh Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal met his counterpart Lt Gen Kyaw Swe in Myanmar in October the same year and talked about yaba trafficking.

Officials in the foreign ministry said every time they sat with their counterparts either in Myanmar or in Dhaka in last few years to improve bilateral relation, they urged Myanmar authorities to take effective steps to stop drug smuggling to Bangladesh.

But the result was zero.

“So, we are left completely hostage to Myanmar now,” said a senior narcotics official. “If the source of the drug cannot be destroyed, it is virtually impossible to stop the trade.”

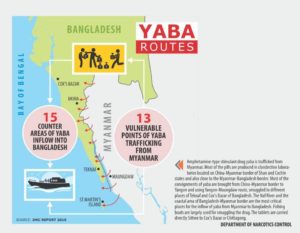

Bangladesh and Myanmar share a 270-kilometer-long border, much of it along the Naf River. Every day, some three lakh water vessels of every kind beginning from small wooden boat to trawlers ply this waterway.

“This makes smuggling of yaba so easy,” said the narcotics official. “There was a time when yaba used to come through land border. Now the bulk of it is carried on boats to Teknaf and Cox’s Bazar. From there it is spread through a cobweb of networks.”

The recent big yaba hauls prove the point that river and sea routes are being used to smuggle the drug. In separate raids conducted at Damdamia and Jhinukhal along the Naf River on the nights of March 15 and 16 this year, BGB and Coast Guards seized over 21 lakh yaba tablets.

Such hauls make little difference as thousands of caches go undetected under the cover of Myanmar’s silence.

COLONIAL ROOT

The root of that eerie silence can be traced back to Myanmar’s colonial past with the British when it was turned into an opium state to its complex relationship with varied ethnic groups to the involvement of its modern time military junta with drug trade.

The CIA also played a role in turning the country into a drug state during its clandestine war with communist China under Mao Zedong.

The Southeast Asia and South Asia regions were no strangers to opium from long ago.

Britain’s colonisation of the region led to a mass scale opium production and actually East India Company’s main business in India was opium.

It found the Chinese tea a thing to barter with silver pillaged from India. By later 18th century, British ships sailed from India laden with silver bullion for Guangzhou.

But then India ran out of silver. The entrepreneurial Company officials found Indian opium as a good exchanging commodity. Very soon the tide changed and ships were carrying opium from India and returning with silver from China.

But China did not take it very kindly. The number of addicts grew very fast who would enter small stolid opium bars, lay on beds and blissfully to go a trance state inhaling opium from long pipes attached to hukkas.

So China banned opium in 1729. But the order was defied by the British. As tension ran high, China wrote to Queen Victoria to stop flooding China with opium. With no response from the Queen, China took action and destroyed 20,000 chests (each of 133 pounds). Angered by this, the British sent a large fleet with 4,000 soldiers under Admiral George Elliot. The British started bombarding Chinese ports and laid siege to Guangzhou and finally occupied Shanghai in 1842. Defeated, China signed a treaty with Britain handing it the island of Hong Kong. Possession of Hong Kong gave the British supremacy in drug trade over other colonial powers.

The British started growing opium in the hills of Yunnan of China bordering Laos and Vietnam then controlled by the French.

The British also took over Burma and the conquest was extended up to the Shan region, an ethnically diverse highlands, by 1890. Shan was already a small-time opium producing land. So China remained the prime land to grow opium and spread the drug to all other Southeast Asian countries.

Britain’s happy colonial days ended with the conquest of Burma by Japan during the Second World War. Fierce battles were fought in Shan between the Japanese troops and Chinese forces sent by Chinese nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek. The Shan ethnic groups got embroiled in this conflict in various ways — some supported the Japanese and some actually fought for the British against the Burmese Independence Army led by Suu Kyi’s father Aung San.

Burma gained its independence in 1948 but its Shan people remained divided and the land completely destroyed by war. Different groups took up arms for complete independence from Burma.

In this context another important geo-political change took place — Chinese communists led by Mao Zedong defeated Chiang Kai-shek and took over power. Chiang retreated to Taiwan with his Nationalist Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) forces. But a large number of KMT forces could not retreat and they moved into Shan province of Burma. A new chapter for Burma’s drug industry began.

From the Shan areas, the KMT started its war against communist China. To finance its war against Mao, the KMT encouraged massive opium cultivation in the hills and turned the Golden Triangle, a touch point of Burma, Laos and Thailand, a major drug smuggling centre where opium was exchanged for gold bars hence the name Golden Triangle.

Then stepped in the CIA which covertly supported KMT to topple Mao, supplying arms and training to the rebels. KMT’s and CIA’s covert operations in the Golden Triangle resulted in large-scale poppy cultivation in Burma’s northeastern hills. Eventually the whole of Shan region turned into pockets of ethnic rebel groups and centre of drug production.

CHEMISTS FLY IN TO MAKE HEROIN

A new chapter in Myanmar’s drug trade began from here. General Ne Win seized power through a coup in 1962 and introduced Burmese Way to Socialism under which all businesses were nationalised. Bereft of income, the whole nation embraced wholesale opium production and trade.

Chemists were flown in from Taiwan and Hong Kong to set up laboratories and diversify opium to heroin. From the Golden Triangle the drugs spread out across the region.

By now, China had started arming its own loyal group the Communist Party of Burma with arms and money to counter Chiang Kai-shek’s army. As arms proliferated, many more armed groups emerged. Burma was now truly a narco-state.

To fight these groups, General Ne Win formed local guard forces called Ka Kwe Ye (KKY) which were given the right to use roads and towns in Shan state to smuggle drugs in exchange for fighting rebel groups. An openly state-sponsored drug trade began.

Respectable businessmen got involved in the trade and government troops provided security for the convoys of drugs.

YABA SPROUTS AS OPIUM WANES

In the 1990s, two things started yaba production in Myanmar.

Opium and heroin trade became costlier and riskier because of international effort to crack down on the drugs. At the same time, heroin production cost escalated. It no longer was that much of a lucrative business. So these two drugs declined in the Shan state.

But Myanmar struck a new gold mine — yaba. It is easy to produce and the raw materials are readily available. So the boom of the crazy pills began.

There are now numerous reports available to indicate that Myanmar’s military is deeply involved with the yaba trade.

Myanmar’s head of the Directorate of the Defence Services Intelligence negotiated a ceasefire with the rebels with special ID cards which made their vehicles immune from police search in Shan State. Instead of heroin and opium, lorries now carry yaba.

“It is clear that the drug lords in the northeast are enjoying protection from the highest level of Burma’s military establishment. The close cooperation between Burma’s drug lords and the SLORC/SPDC has led many to speculate that the government may be more closely involved in the trade than just providing protection,” wrote Bertil Lintner, a Swedish journalist known for expertise on Burmese issues, in a report headlined The Golden Triangle Opium Trade: An Overview, in 2000.

It is now estimated that Myanmar’s drug trade income is twice the GDP of the country and it is suggested that Myanmar’s army build-up is financed by drug money.

David Bernstein and Leslie Kean, two journalists of The Nation in a report on Burma in 1996 established earlier this point in a report headlined “People of the Opiate: Burma’s Dictatorship and Drugs”. Their report exposed the workings of Burma’s new narco-dictatorship, which has incorporated the booming drug trade into the permanent economy of the country. They showed that despite Burma not having any official source of foreign currency, it purchased arms over $1 billion.

The US embassy in Yangon had estimated back in 1996 when Yaba was just on the rise the unaccountable foreign currency inflow in Myanmar, basically drug money, was $400 million. The 1997 Asian financial crisis also gave an indication of the extent of drug economy of Myanmar. Its currency after its initial fall remained stable indicating that Myanmar had a deep and unexplained foreign currency reserve thought to be drug money. The drug money got more entrenched into Myanmar’s economy after the government announced whitening of repatriated funds of dubious origin after a ceasefire deal with ethnic rebels.

The existence of the ethnic rebels makes curbing the drug business even more difficult for Myanmar even if it ever wants. With traditional agriculture destroyed by drugs, any crackdown on yaba would mean clipping the money supply for the region and that would lead to fresh rebellion. Myanmar would not like to see insurgency resurface.

But matters have become more difficult with Myanmar’s military involvement with drug lords. One of the top drug lords Lin Mingxian is reported to have given huge protection money to military intelligence. A Reuters report in 1999 showed how the military intelligence took reporters to an anniversary celebration between the government and the rebels where they were introduced to Lin, Also an ethnic group leader. Lin was even a delegate to the regime’s National Convention in the 1990s.

The matter became more glaring when in early 2005 eight ethnic rebel leaders belonging to UWSA were indicted by a Brooklyn federal grand jury in the US. But the Myanmar government refused to arrest any of them or confiscate their shell companies used for drug trade.

There are many more examples of Myanmar’s military involvement with drug cartels. In 2003, Shan Herald Agency of News (S.H.A.N) published a list of 93 yaba factories run with complicity of military.

The Lahu National Development Organisation, works for welfare of Lahu people in Myanmar, in October 2016 exposed Myanmar army’s reliance on drug trade to subsidise its operation in Shan State.

The report, “Naypyidaw’s drug addiction,” reveals the key role of Myanmar army militia in hosting jungle labs for methamphetamine pills.

“The Burma Army needs local militia to control eastern Shan State, and the cost of their loyalty is an unhindered drug trade,” said LNDO director Japhet Jagui.

The book Hand in Glove published by S.H.A. N in 2006 mentions the existence of a yaba factory on a ten-acre land wedged between the command posts of SPDC Light Infantry Battalion 331 and 359 close to Thai border.

A POROUS BORDER POSES TOUGH CHALLENGE

The US Department of State has argued for several years that Myanmar has “failed demonstrably” to meet international anti-drug obligations, said Tom Kramer, a political scientist and with over 15-years of working experience on Burma and its border regions and works for Transitional Institute of Netherlands.

Among other things, the US stressed the failure to “investigate and prosecute senior military officials for drug-related corruption.”

According to a 2013 US Department of State report: “Many inside Burma assume some senior government officials benefit financially from narcotics trafficking, but these assumptions have never been confirmed through arrests, convictions, or other public revelations. Credible reports by NGOs and media claims that mid-level military officers and government officials were engaged in drug-related corruption; however, no military officer above the rank of colonel has ever been charged with drug-related corruption.”

So when the Myanmar junta is so insidiously involved in the yaba trade Bangladesh and other regional countries find it hard to stop the flow of yaba.

“We have check posts every three kilometres along the Naf River,” said Teknaf-based BGB Battalion Commander Lt Col Asaduzzaman Chowdhury. “At night it is difficult to detect which boat is carrying yaba and which not. However, we are relentlessly trying to stop yaba smuggling.”

Ninety percent of the yaba enter Bangladesh through the Naf, said a report by the Association for the Prevention of Drug Abuse.

The Rohingya influx since August last year has also made it difficult to fight yaba. Many of the Rohingyas along with locals are engaged in yaba trade. It is not possible to check every person who moves around, Asaduzzaman said.

There is no end view of the Rohingya crisis as Myanmar has shown no interest in repatriation of the one million refugees in Cox’s Bazar. World diplomatic efforts also seem to have fizzled out after eight months into the crisis that started with the ethnic cleansing that Myanmar commenced.

The task gets tougher with some of the law enforcing agency people getting involved in the yaba trade, one of the most startling incident being the September 2017 haul of yaba in Cox’s Bazar. Police caught a cache of 7.30 lakh yaba pills and showed the seizure as only 8,000 pieces. The rest the police sold to yaba dealers for Tk 8 crore.

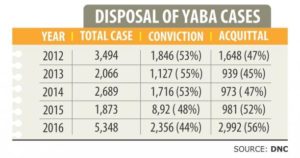

Former inspector general of police AKM Shahidul Huq at a press conference at the police headquarters in January said yaba has become unstoppable although cases have been filed against about three lakh people.

Narcotics department officials also feel the same way.

“The situation has gone out of hand,” a narcotics intelligence high official admitted. He showed us pictures of various top yaba lords in Dhaka. None of them could be arrested so far. “We raid yaba selling points. Within 15 minutes of our leaving the spot, the peddlers return and start selling. It has become impossible to stop the drug.”

With the yaba threat so enormous, a taskforce headed by the director (operations and intelligence) of narcotics department has been formed in April last year to conduct monthly raids to catch yaba dealers in Cox’s Bazar. A temporary camp of the narcotics department has been set up in Teknaf.

A national task force has been formed headed by the Principal Secretary of the Prime Minister Office to fight drug abuse. Another committee headed by the home secretary has been formed to ensure enforcement of the measures proposed by the taskforce.

The narcotics department also finds itself strapped with lack of manpower. Currently it has 2,700 staff which the department finds too small to fight yaba. It has proposed to the government a new organogram seeking manpower of 8,000.

At the end of last year, DNC has sent a revised list of 419 Yaba dealers to the home ministry but actions are yet to come.

The narcotics department has sought to the government the phone call tracking equipments to enhance its drive against yaba lords.

The narcotics department has drafted a law keeping a provision of death penalty for producing or processing more than 200 grams of yaba pills or the same amount of its ingredients.

“But the main challenge is to stop yaba at the source in Myanmar,” said a top narcotics department official. “If there is demand in the market, the drug will find its way somehow. The challenge is now to press Myanmar to stop yaba production.”

His words prove true for many regional countries which took very stern measures to check yaba and yet failed. Thailand is one example. In 2003, Thai government declared a war on drug as yaba was having a devastating impact on the society. Some 3,000 suspected drug peddlers were killed in three months and the jails were overflowing with mass arrests. Yaba incursion stopped for a short time and then it came back with the same force.

A curse of World War II

Yaba, a combination of a number of stimulants including methamphetamine, is also known as Nazi speed. This name tells the history of abuse of this drug to energize soldiers in the battle grounds to kill opponents during the World War II.

German writer Norman Ohler in his book, “Der Totale Rausch” (The Total Rush in English) published in 2015 found that many in the Nazi regime used drugs regularly, from the soldiers of the German armed forces all the way up to Hitler himself. The use of methamphetamine, better known as crystal meth, was particularly prevalent: A pill form of the drug called Pervitin was distributed by the millions to the German troops before the successful invasion of France in 1940.

Prior to the invasion, a “stimulant decree” was sent out to army doctors, recommending that soldiers take one tablet per day, two at night in short sequence, and another one or two tablets after two or three hours if necessary. The authorities ordered 35m tablets for the army and the factory increased production.

The Centre for Substance Abuse Research, the University of Maryland-based institute that addresses issues related to alcohol and other drugs, however, says during World War II, military in the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and Japan used methamphetamines to fight fatigue and enhance performance.

After the war, it says, when military methamphetamine supplies became available to the public, abuse of intravenous methamphetamine became an epidemic in Japan.

During the 1950s in the United States, methamphetamine tablets were legally manufactured, and used non-medically by students, truck drivers, and athletes.

In 1970, the Controlled Substance Act restricted the use of methamphetamine and made it a Schedule II substance2. Since yaba contains methamphetamine, it is also illegal.

Today, the United Wa State Army of Myanmar, the largest drug trafficking organization, is the primary manufacturer of yaba in Southeast Asia. Thailand and Bangladesh are the primary market for these tablets.

The World War II is the most destructive war in all of history. Its exact cost in human lives is unknown, but casualties in this war may have totalled over 60 million service personnel and civilians killed.

After more than seven decades, the drug used by soldiers to kill opponents in the battle field has been destructing lives of millions in peace time.

Source: The Daily Star Bangladesh; May 12, 2018