The biggest of these opposition parties, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), and its allies say they have no faith that Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina will hold a free and fair election.

They called on her to step down and allow the polls to be held under a neutral interim government – a demand she rejected. So the candidates on the ballot will all be from the Awami League, its allies or independents.

“Democracy is dead in Bangladesh. What we are going to see in January is a fake election,” Abdul Moyeen Khan, a senior BNP leader, told the BBC.

He echoes wider concerns that Sheikh Hasina has grown increasingly autocratic over the years. Critics question why the international community is not doing more to hold her administration to account.

Her government flatly rejects accusations it is undemocratic.

“Elections are determined by the participation of the people to vote. There are many political parties, apart from the BNP taking part in this election,” Law Minister Anisul Huq told the BBC.

The cost of growth

Bangladesh under Ms Hasina presents a contrasting picture. The Muslim-majority nation, once one of the world’s poorest, has achieved credible economic success under her leadership since 2009.

It’s now one of the fastest-growing economies in the region, even surpassing its giant neighbour India. Its per capita income has tripled in the last decade and the World Bank estimates that more than 25 million people have been lifted out of poverty in the last 20 years.

Using the country’s own funds, loans and development assistance, Ms Hasina’s government has undertaken huge infrastructure projects, including the flagship $2.9bn Padma bridge across the Ganges. The bridge alone is expected to increase GDP by 1.23%.

But in the wake of the pandemic, Bangladesh has been struggling with the escalating cost of living. Inflation was around 9.5% in November.

Its foreign exchange reserves have dropped from a record $48bn (£38bn) in August 2021 to around $20bn now – not enough for three months of imports. Its foreign debt has also doubled since 2016.

Critics say economic success has come at the cost of democracy and human rights, and allege that Ms Hasina’s rule has been marked by repressive authoritarian measures against her political opponents, detractors and the media.

In August more than 170 global figures including former US president Barack Obama, Virgin Group founder Richard Branson and U2 lead singer Bono, wrote an open letter to Ms Hasina urging her to stop the “continuous judicial harassment” of Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus.

And in recent months, many senior BNP leaders have been arrested, along with thousands of supporters following anti-government protests.

Mr Khan – one of the few senior leaders of the BNP not under arrest – alleges that more than 20,000 party supporters have been arrested on “fictitious and concocted charges”, while cases have been filed against millions of party activists.

The government denies this.

“I have checked and it’s half that number,” says Mr Huq, referring to the number of its supporters the BNP alleges are in detention. “Some of the cases go back to violent incidents that took place during the 2001 and 2014 elections.”

However, the statistics show politically-motivated arrests, disappearances, killings and other abuses rising under Ms Hasina. Human Rights Watch recently called the arrests of opposition supporters a “violent autocratic crackdown” by the government.

It’s a remarkable turnaround for a leader who once fought for multi-party democracy.

In the 1980s Sheikh Hasina joined hands with other opposition leaders, including her bitter rival Begum Khaleda Zia, to hold pro-democracy street protests during the rule of General Hussain Muhammed Ershad.

The eldest daughter of the country’s founding leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Ms Hasina was first elected to power in a multi-party election in 1996. She then lost the 2001 poll to the BNP led by Khaleda Zia.

The two women are locally described as the “battling Begums”. Begum refers to a Muslim woman of high rank.

With Begum Zia now effectively under house arrest on corruption charges and facing health complications, the BNP lacks dynamic leadership on the ground.

This has been compounded by the systematic arrest and conviction of opposition leaders and supporters. Many argue that this has been deliberately done by the Awami League to cripple the BNP ahead of the poll.

Many supporters of the BNP, like Syed Mia, have gone into hiding to escape persecution. The 28-year-old, whose name we have changed to protect his identity, spent a month in jail in September for participating in a political protest.

Mr Mia currently lives in a tent with three of his party colleagues in a forest area. They are all wanted in connection with arson and violence offences they are accused of committing during a rally.

“We have been in hiding for over a month and we keep changing our hideouts. All the charges against us are false,” Mr Mia told the BBC.

The worsening human rights situation has caused concern among international agencies.

“The current scenario looks like a broad-based or even an indiscriminate approach to round up thousands of opposition party workers often in relation to the same incident,” Rory Mungoven, Asia-Pacific chief at the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva, told the BBC.

“It seems a much broader suppression of the opposition rather than a targeted response to any violence.”

A group of UN special rapporteurs also expressed alarm in November. “The weaponisation of the judicial system to attack journalists, human rights defenders and civil society leaders diminishes the independence of the judiciary and erodes fundamental human rights,” they said.

But Law Minister Huq says the government has nothing to do with the courts: “The judiciary is absolutely independent in the country.”

It’s not just the staggeringly high number of arrests and convictions that worry rights groups. They also say they have documented hundreds of cases of enforced disappearances and extra-judicial killings by security forces since 2009.

The government flatly denies claims that it’s behind such abuses – but it also severely restricts visits to foreign journalists who want to investigate such allegations. Most local journalists have stopped looking into cases like these, fearing for their safety.

The number of extra-judicial killings has dropped significantly since 2021 when the US imposed sanctions on the Rapid Action Battalion, a notorious para-military force, and seven of its current and former officers.

But the limited sanctions by the US have not improved the overall human rights situation in Bangladesh. That’s why some politicians are calling for tougher action by Western nations.

A diplomatic balancing act

“The European Commission should hold Bangladesh accountable on the democratic situation. It should consider withdrawing tariff-free access given to products from Bangladesh” said Karen Melchior, a member of the European Parliament.

Bangladesh is the world’s second-largest garment exporter after China. Last year it shipped more than $45bn worth of ready-to-wear garments, mostly to Europe and the US.

The question many ask is why Western nations, which have such enormous economic clout, allow Sheikh Hasina to act with impunity while systematically dismantling democratic institutions.

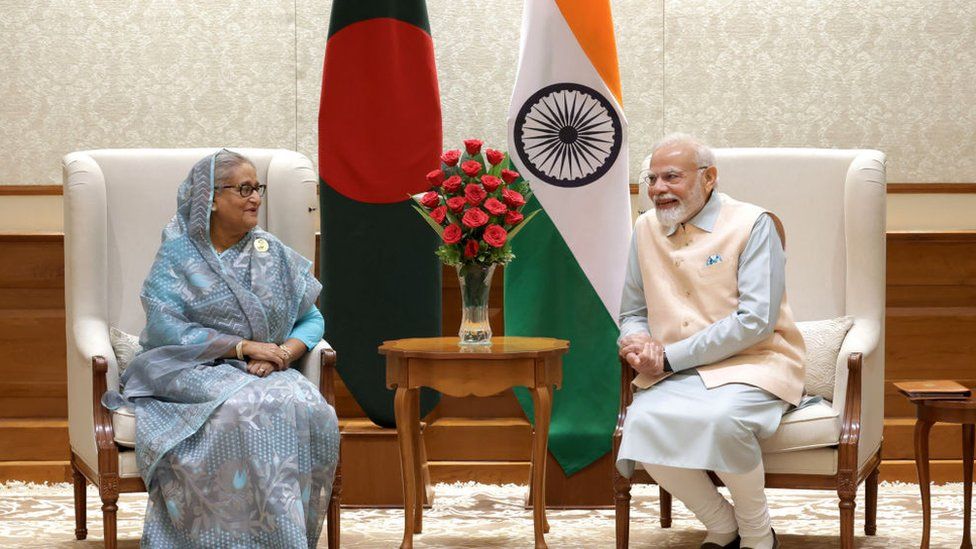

The elephant in the room is neighbouring India, which opposes any coercive action against Bangladesh. Delhi wants road and river transport access for its seven north-eastern states through Bangladesh.

India is also concerned about the “chicken’s neck”, a 20km (12-mile) land corridor that runs between Nepal, Bangladesh and Bhutan, linking its north-eastern states to the rest of India. Officials in Delhi are afraid it is strategically vulnerable in any potential conflict with India’s rival, China.

Soon after coming to power in 2009, Ms Hasina also won favour with Delhi after acting against ethnic insurgent groups in India’s north-east, some which were operating along the border.

There are concerns that any excessive arm twisting could push Dhaka towards China. Beijing is already keen to extend its footprint in Bangladesh as it battles for regional supremacy with India.

For now, Ms Hasina appears to have a clear path to power. But challenges to her authority may soon appear from other quarters.

Dhaka has already asked the International Monetary Fund for a loan of $4.7bn to avert any balance of payment crisis. So it’s likely the government will have to take some tough measures after the elections to help boost the economy.

Her opponents may not be standing, but public fallout from austerity policies could pose an early challenge to Ms Hasina and her Awami League.