A five part series published in the Financial Express on various dates starting from 15 June 2019

Global recovery, output and trade trends

First of a five-part series titled “Post-graduation globalisation trends and challenges for Bangladesh”

Shamsul Alam | June 15, 2019

The graduation of Bangladesh from the list of Least Developed Countries (LDC) is unquestionably one of the greatest national achievements of the country. It is an international recognition of substantial progress made by this country over past few decades. The graduation is a giant step towards Bangladesh’s deeper economic integration with the global economy.

But, when seen from the context of the current global environment, this accomplishment could not have come at a more inconvenient time. The global economy has suffered from a series of unfavourable events throughout the last decade. Once unanimously accepted norms of international trade regime are facing fundamental questions regarding impact on resources and welfare distribution. As a result, a few ominous themes have appeared on global centre stage including slow trade and faltering recovery, rise of economic protectionism, uncertain fate of multilateral trading system, and the potential impacts of automation on employment in the upcoming industrial revolution.

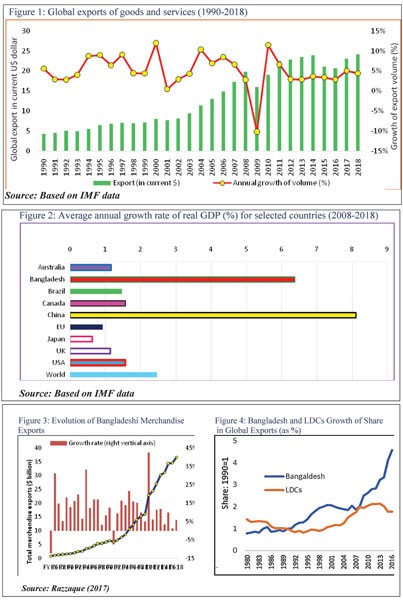

Even more than a decade after the financial crisis, the world economy is still struggling to return to its pre-crisis era growth trajectory. Global trade has been on the rise since the inception of World Trade Organisation (WTO), and its successful early negotiations for trade liberalisation. Withstanding cyclical recessionary impacts, global trade saw a steady average expansion of above 6.0 per cent per year between 1990 and 2008. This growth is even higher if we consider it from 1980 (about 6.5 per cent annually). But the scenario has changed drastically since the 2007-2008 global financial crisis (GFC). The average annual trade volume growth for 2012-16 has been 2.9 per cent, which is less than half the comparable growth achieved during the 1990s and 2000-08. If International Monetary Fund (IMF) projections turn out to be correct, 2012-21 would be the slowest decade of trade expansion since World War II.

The magnitude of this slowdown is somewhat hidden underneath, when the data on ‘real’ or ‘volume’ growth are used. Measured in current US dollar terms (shown in Figure 1), world exports of goods and services contracted by an astounding $2.8 trillion in 2015 (from 2014) and then again fell by about $500 billion in 2016 (from 2015). That is, in value terms, global exports of goods and services in 2015 declined by almost 11 per cent followed by another 3.5 per cent drop in 2016. As a result, global exports in 2016 were just roughly around the same level as in 2008. The situation has slightly improved in 2017 and 2018. Despite the much appreciated tailwind during a difficult time, the trend of slow growth persists strongly across the globe.

The rate of economic recovery has been largely uneven. Figure 2 shows the rate of average annual growth of real gross domestic product (GDP) since the crisis for a few selected economies. The rate of GDP expansion appears to have peaked in some major economies and growth has become less synchronised. After decades of fast growth, China has started showing signs of sluggishness with lower than 7.0 per cent GDP growth since 2015. Other large developing economies including Brazil, Mexico and Turkey have started to slow down. Developed economies have been the prime victims of the financial crisis and the recession that followed. Although USA has indicated stronger recovery (more than 2.5 per cent growth rate) in last couple of years, other advanced economies are far from it. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries including Japan, Canada, Australia, United Kingdom (UK) and the European Union (EU) are growing at lower than 2.0 per cent rate per year. Overall, the global economy has increased at the rate of only 2.47 per cent between 2008 and 2018.

This trend of weak global trade expansion has adverse effects on LDCs as well. A longstanding international development objective has been securing stronger participation of the poorest and the most vulnerable countries (including the LDCs) in world trade. Although some decent progress was made regarding this during the 2000s, consequences in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis have reversed the trend. During 2000-2008, LDC exports grew almost five-fold, from U$ 43 billion to about U$ 200 billion. But in 2015, LDC exports stood just about the same as in 2008, only at US$201 billion. Moreover, export-to-GDP ratios of LDCs have been on average about 25 per cent since 2008, substantially below the developing country average of about 35 per cent.

Even during these critical periods of global trade, Bangladesh has maintained a stellar performance to secure growth in merchandised exports. In fact, Bangladesh became the best performing LDC in terms export by a distant margin. During the 1980s, Bangladeshi merchandise exports grew by $0.50 billion. In the following decades, that expanded rapidly: by $3.4 billion in the 1990s, followed by another $10 billion in the 2000s; and then a staggering $20 billion between 2010 and 2018, when the total exports crossed $36.6 billion mark. Bangladesh managed to attain a radical structural shift in exports, moving towards manufacturing exports (readymade garments) from traditional agricultural goods (jute, tea, fish etc.). This is something that most countries from sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America have been unable to do despite having more favourable foothold in the race and better starting positions. Between 1990 and 2016 while world merchandise exports grew at a compound annual average rate of 5.80 per cent, Bangladesh managed to grow twice as fast. Since 1990, Bangladesh has seen a four-fold rise in its share in world exports in comparison with 1.75 times achieved by LDCs in general (Figures 3 and 4).

Despite these improvements, Bangladesh is not immune to the existing trends of the global market. Especially, uneven expansion of the global economy has strong implications for the local exporters. The developed economies are the most prominent export destinations of Bangladesh. Their inertia in attaining full-speed recovery is costing export prospects of local manufacturers. Primarily, weakened economic progress of the European Union, Canada, Japan and Australia resulted to weaker aggregate demand in those markets. If significant unemployment or underemployment persists in those countries, consumers spending will fall. Even though Bangladesh’s export performance remained impressively resilient and increased in the midst of all the turmoil, the country cannot materialise its full potential with a slowed-down global economy.

Another important consequence of the slow global economy and international trade is the potential impact on achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs). The 2030 Agenda for SDG provides an elaborate role – both direct as well as cross-cutting – for international trade in achieving many specific goals (SDGs) and targets. Trade appears directly under seven goals concerning hunger, health and wellbeing, employment, infrastructure, inequality, conservative use of oceans, and strengthening partnerships. Compared to MDGs, the SDGs go further in clearly identifying the ‘means of implementation’, where trade has been given a prominent role. The ability of trade at creating wealth through value addition and then magnifying it through the value chains makes it an enormously powerful component in pursuit of attaining inclusive growth.

As we already know, LDCs suffer from structural capacity and other constraints which restrict them from participating in meaningful value addition. International trade offers them an opportunity to attain inclusive and sustainable development in the LDCs. As LDCs are increasingly integrated into the global value chains, their overall contribution in trade increases. This allows them to have access to crucial foreign exchange and capital stock for future investments.

According to the World Investment Report 2014 of United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), developing and least developed economies face an annual investment gap of $2.5 trillion per year in meeting the SDGs. It is high time the global community considered actions that will revive global trade flows and enhance the participation of LDCs including Bangladesh at improving the situation.

Coping with rising protectionism in developed countries

Shamsul Alam | June 16, 2019

In a period when global economy is already suffering from post-recession inertia and failing to pick up strong pace of recovery, surge of protectionist trade policies has emerged as a new obstacle in the path of promoting inclusive growth through international trade. While a number of cyclical components such as weak prices of energy or metal items and several structural factors like consolidation of global value chains have contributed to the persistence of global trade slowdown, protectionist trade interventions by advanced economies have also played their part in the process. In fact, the arrival of economic protectionism in the worst performing decade for trade growths has cornered any efforts of international commerce liberalisation.

To understand what fuelled the current spectre of global protectionism, which has become evident with implementation of “economic nationalism” in some western democracies, it is important to understand how global trade has affected other economic ingredients across the globe. There is a clear consensus among economists about trade liberalisation improving wealth and income, and free trade benefiting a country as a whole. It is equally true that both protectionism and system of free trade create winners and losers. While protectionism ends up handpicking winners amongst industries and jobs which are more influential to governments, free trade picks its winners based on competition. Jobs and industries that are less competitive cede to more competitive foreign entities. But far more importantly for any country, freer trade means cut in consumer prices, increased wealth, higher productivity and higher efficiency in allocation of resources. Setbacks of less competitive or uncompetitive businesses in a country gradually open up investment and expansion opportunities to more competitive industries of the same country. This mostly translates into concentrating efforts on items in which the country has a comparative advantage. For Bangladesh, a shift towards liberalisation during 1980’s and 1990’s from heavily protectionist regime resulted in a boom in the competitive readymade garments (RMG) sector as it overtook jute as the prominent export item.

Inevitably, free trade does leave some people behind. And betterment of these people requires supportive measures from governments. In case of some western democracies, progressive trade liberalisation displaced significant amount of manufacturing job overseas, to more competitive workers of emerging economies. If a substantial number of losers from global trade is left to the hands of markets without adequate government interventions, they are more likely to remain unemployed or underemployed, and become increasingly reliant on social protection. Without investing in workers, developing human capital and enhancing productivity of workers, the gains from free-trade give asymmetric rise to wealth inequality. And when this inequality is translated into socio-political system, it creates faction and aversion against global trade. For example, according to the estimates of Economic Policy Institute of United States, the North American Free Trade Agreement has resulted in 682,000 jobs to be lost or displaced from USA.

Such results may create mass-disapproval about free-trade agreements. And the constituencies with highest job displacement become increasingly sceptical about future trade agreements. In addition to that, several political-economic factors, such as role of ultra-rich private financial institutions in global economic meltdown of 2008, use of scarce public funds in commercial bailouts and slow pace of economic recovery have resulted in groups of disaffected population worldwide. High income-inequality and stagnant real wages in many advanced democracies added fuel to the fire. And the refugee crisis across the globe exacerbated this situation with rise of anti-immigration political narratives. Under these circumstances, populist political ideologies that identify globalisation and free trade as threatening component for national economic integrity received public appreciation. And the dismal state of affairs has accentuated when anti-globalist agendas resulted in political upheavals in elections of Europe and the USA.

The globalisation backlash resulting from global financial crisis has also fuelled a rise in protectionism, with different countries implementing various trade-restrictive measures. Most protectionist measures in the existing global system have been proliferated and persisted since the crisis. During that period, both advanced and developing economies started applying protectionist options to safeguard their economy from global fluctuations. The World Trade Organisation (WTO) estimates, a total of 1,583 trade restrictive measures have been imposed by G20 countries since November 2008, and only a quarter of these measures have been removed. These restrictions have had a detrimental impact on trade flows, particularly for the world’s poorest countries. According to another estimate (Evenett & Fritz, 2015), least developed countries (LDCs) have incurred a loss of $264 billion in exports as a result of these protectionist measures. In other words, the value of LDC exports could have been 31 per cent higher if post-crisis protectionism had been avoided.

Like other LDCs, Bangladesh has also been affected by these protectionist measures. According to the global trade alert (2019), there are 57 protectionist interventions that harm Bangladeshi export initiatives. On the contrary, Bangladesh experienced only 29 interventions since the crisis from foreign governments which were liberalising in nature or promoted trade. In more recent times, two largest economies of the world got embroiled in retaliatory trade disputes, starting with USA imposing a series of high tariff on Chinese imports. But Pew Research Centre (2018) pointed out, Bangladesh pays highest amount of tariff on total import value in the US market (Figure 5). This is because, Bangladesh does not receive any generalised system of preference in US market, and the Most favoured nations (MFN) tariffs set by US authorities for the most prominent Bangladeshi export (RMG) is high.

As the global economy goes through a difficult time, there is a significant possibility that the increasingly anti-trade political rhetoric could spin out of control, with damaging consequences for the international community. The European Central Bank (ECB) assumes that global trade will grow at slower rate in 2019 than previous year and rise of protectionist trade regimes is a primary contributing factor behind that situation. Consequently, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has also issued warnings about slower continental growth over the next two years due to softer demands and persistent trade tensions (2019). Nonetheless, the future prospects are not necessarily bleak for Bangladesh. Small-scale trade disputes between advanced and major developing economies may divert investments to alternative sources of emerging markets. Such trade spats between big economies create short or medium-term demand for suppliers who are competitive enough to deliver under difficult circumstances. If local exporters are keen and competitive enough to attract some of those attentions, it may end up giving Bangladesh an additional boost to exports during the LDC transition, while some preferential market access are still available. However, in case of a full-scale global trade war, all countries, including Bangladesh, may end up losing valuable share of exports and face further trade slowdown.

Despite progress, Bangladesh itself continues to impose high trade protection. An important policy question is whether trade protection helped gross domestic product (GDP) growth. On the surface it would appear that high GDP growth co-existed with high trade protection. Indeed, as shown in Figure 6, impressive economic growth has been accompanied by a much higher level of tariff protection than all other successful developing countries including China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. During the period 2010-17, except for just one (Chad), there was no country that had applied tariff rate higher than Bangladesh (approximately 12 per cent) and achieved average growth rate higher than Bangladesh. However, this simple correlation is misleading. The two major drivers of growth have been the ready-made garments (RMG) exports revolution and the surge in foreign remittances, both of which were associated with an open trade and factor market regime. Indeed, there is evidence that trade protection-based manufacturing performed worse than export-oriented manufacturing. Similarly, job creation was better in export-oriented RMG than trade-protected domestic industries. Furthermore, as will be explored in detail in latter parts of this series, large trade protection has created a major anti-export bias that has hurt export diversification and export growth.

In addition to the need to lower trade protection to promote export diversification, with LDC graduation on the cards, trade liberalisation will become an issue of concern. Bangladesh will have to trim down certain protectionist measures to remain consistent with core WTO trade agreements. This will be a test of prudence of policymakers and adaptiveness of domestic industries. However, in a world where protectionism is rising, Bangladesh cannot singlehandedly cut own tariff rates and open the market for other parties. This calls for strong trade negotiations and engaging in meaningful regional or bilateral trade agreements. Discussions in the following sections will shed light on these issues.

State of multilateralism: Rise of regional and plurilateral trade agreements

Third of a five-part series titled “Post-graduation globalisation trends and challenges for Bangladesh”

Shamsul Alam | June 17, 2019

International trade has been the primary engine of facilitating income and accumulating wealth around the world in the post-WWII period. The goal of progressive trade liberalisation has been universally accepted and pursued under the singular body of the multilateral trade regime (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade [GATT] since 1948, which became World Trade Organisation [WTO] in 1994) for nearly seven decades. During this period, trade restrictions were significantly reduced, non-tariff barriers were cut drastically and applicable tariff rates were slashed down to record low levels worldwide. Nonetheless, nearly twenty years after the WTO’s establishment, trade multilateralism has reached a crossroads. With Doha Development Agenda (DDA) negotiations going on since 2001, WTO’s role, relevance or competency in greater trade liberalisation and providing relevant governance are under increased scrutiny. At the same time, with proliferation and deepening of regional trading arrangements (RTAs), control over new or broader horizon of international trade rules are leaning towards individual economies. Therefore, the organisation is being sidelined and its members are showing increasingly greater reluctance in multilateral trade discussions. As LDC (Least Developed Countries) graduation approaches alongside a stalled multilateral trade regime, Bangladesh is also confronted with a challenge of expanding exports through outside multilateralism – through bilateral and regional trade negotiations.

Under the current structure of global trade governance, most countries including Bangladesh are involved in two broad types of trading arrangements. The first one is multilateral trading arrangements and processes led by WTO while the rest fall under the broad definition of preferential or regional trading agreements (PTAs or RTAs). When RTAs contain several signatories across continents, they become mega-RTAs (such as proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership). Another type of arrangement, like the plurilateral agreements, is negotiated under facilities of multilateral system, but they do not include all members of that system. When WTO members are given choices to agree or decline a new set of rules on a voluntary basis, it becomes a plurilateral trade agreement. Besides, there exist many other forms of trade cooperation arrangements that are often reflected in motion of unions and agreements between countries. These instruments could include expression of intent for increased trade and investment flows, initiating trade negotiations, greater cooperation involving the private sectors, etc. with many of the provisions being non-committal in nature. However, any legally binding trading arrangements must be consistent with WTO rules.

Although, WTO is based upon a key principle of non-discrimination between signatories (i.e. not favouring one trading partner over another), one major exception allows enabling members to sign RTAs. Three sets of WTO rules will have to be observed before entering any bilateral or regional trading arrangements. These rules relate to the formation and operation of RTAs (including customs union and free trade areas) covering trade in goods (Article XXIV of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994), regional or global arrangements for trade in goods between developing country members (the Enabling Clause), as well as agreements covering trade in services (Article V of the General Agreement on Trade in Services). The WTO requires that, RTAs must cover substantially all trade unless they are under the Enabling Clause. However, there is no quantitatively specified definition for ‘substantially all trade’.

When WTO was established after the Uruguay round (1986-1994) negotiation of GATT, at one hand, it was meant to be the parliament of international trade, dictating terms through an all-encompassing system of multilateralism, and achieving a freer world for global economy that pushes for globalisation agendas through negotiation and progressive liberalisation of trade barriers. On the other hand, it was also meant to be the enforcer of the regime by using revolutionary mechanisms such as even-handed dispute settlement, and making sure members abide by the binding agreements. WTO managed to bring countries from both developed and developing economies to the same table and provided them with equal footing in the negotiation process. WTO also managed to acknowledge the supply side constraints of LDCs and necessity of special & differential treatment (S&DT) for most vulnerable countries of the world, through necessary provisions in binding agreements. In order to streamline the system of global trade, WTO provided a singular stage where the weakest countries can represent their stakes in global trade as the strongest one.

In the earlier stages of global trade negotiations, regionalism was thought to be a faster way of reaching multilateralism. Many protectionist and small economies preferred taking smaller steps towards trade liberalisation by opening domestic markets to regional or prominent trade partners first. The WTO also encouraged members in RTA, by setting up basic frameworks or laying down groundwork for agreements with binding agreements like GATT, General Agreement on Trade Services (GATS) and Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

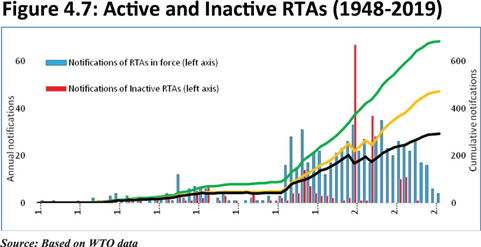

This trend of trade liberalisation in early 1990s saw a boom in regionalism. And global trade started picking up pace, which continued an average growth of 6 per cent till 2008. (Figure 4.7 shows how RTAs proliferated over the years.) In many cases, countries aggressively signed a number of RTAs with their trading partners, which resulted in some redundant agreements. Till April 2019, there were 289 physical RTAs in force, while the WTO has been directly notified about 686 RTAs (active and dormant). Currently, G20 country members of the WTO often interpret it as covering 80 per cent of all trade between the RTA partners (South Centre, 2008).

RTAS EMERGE AS A STUMBLING BLOCK TO MULTILATERALISM: This seemingly innocuous proliferation of RTAs soon emerged as a stumbling block to multilateralism itself. One of the biggest problems with regional, preferential and bilateral trade deals is that they discriminate against excluded members. As a result, every time an RTA is signed, excluded members face substantial preference erosion. For example, when USA signed African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and offered Duty-Free Quota-Free (DFQF) access for numerous products originating from Sub-Saharan Africa, it caused an erosion of preference for non-African LDCs, including Bangladesh. It made African products more competitive in the US market, at the expense of products from excluded parties. These DFQF access from African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) resulted in a boom of apparel industry in southern African countries while a more competitive readymade garments (RMG) exporters from Bangladesh pay more than 15 per cent tariff on exported value. As we can see, discrimination caused by RTAs are distortionary in nature, as more competitive producers are forced to pay a high most-favoured nation (MFN) tariff, while uncompetitive actors are made competitive artificially and get access to greater markets.

Apart from being trade distortionary, regionalism can even become detrimental for trade liberalisation. Instead of expanding trade, large number of trade arrangements between different countries can even slow it down. Signing multiple FTAs across the nations creates complication in applying domestic rules of origin, a situation termed as the “spaghetti bowl effect”. Such phenomenon leads to discriminatory trade policy, as the same commodity is subjected to different tariffs and tariff reduction trajectories for the purpose of domestic preferences. With the increase in FTAs throughout the international economy, the phenomenon has led to paradoxical and often contradictory outcomes amongst bilateral and multilateral trade partners. In addition to these issues, engaging in RTAs or FTAs require a combination of significant resources including skilled negotiators, trade experts, legal professionals, academics, unison of different private industries, time and money. These are scarce in most small and vulnerable countries. That being the case, LDCs rely more on successful negotiations from WTO as it is not possible for them to engage in many regional agreements,

It can also be noted that, the proposed mega-regional arrangements such as Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), flagrantly discriminate against every single excluded actors of global trade, especially emerging economies and all LDCs including Bangladesh. In many cases, mega-regional agreements are politicised, and uses trade as a weapon to enforce geopolitical hierarchy. Therefore, in several ways, the original multilateral dream of trade liberalisation is facing dire consequences from multiplication of RTAs. And WTO’s agenda of economic integration is being thrown in the backseat, with countries showing reluctance in making meaningful multilateral progress and providing more efforts in RTA negotiations. Therefore, regionalism has eventually been turned into a stumbling block in the path of multilateralism and greater international integration, instead of helping the original cause.

TFA – A GLIMMER OF HOPE: Although WTO is going through virtually a stalemate, with both developed and developing countries being super-protective about their interests and repeatedly declining to make necessary concessions about individual demands, enforcement of the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) came as a glimmer of hope. Despite being a plurilateral agreement, it has potentials to increase global merchandise export by $1.0 trillion per annum. This deal is considered as one of the most important achievements of WTO since establishment. After ratifying the TFA as the 94th country in 2016, Bangladesh is currently at the implementation stage of this agreement. Overall, Bangladesh has been tremendously benefited from WTO provisions. Supports through LDC specific enabling clause, S&DT preferences, TRIPS waiver, services waiver have been discussed earlier. The country also served twice as the coordinator of the LDCs in Geneva in 2007 and in 2011, leading negotiations on behalf of the group, championing their interests in various areas including greater market access, increased flexibility in the development of multilateral trade rules, and targeted assistance for improving trade infrastructure among others.

Despite the challenges, rules-based multilateralism is an indispensable global public good (The Commonwealth, 2015). Through its trade rules and binding dispute settlement system, the WTO-led multilateral trading system formally provides a level playing field to all its members. There is an urgent imperative for those who wish to promote a sustainable, inclusive, equitable and dynamic global rules-based multilateral agenda to rally forces. In absence of a strong and effective multilateral trade regime, LDCs and small actors of global economy are the biggest losers. The Istanbul Programme of Action (IPoA) of 2011-2020 for LDCs set a target to double the LDC share of global exports by 2020. This share was 1.05 per cent at the beginning of IPoA implementation, then declined to 0.96 per cent in 2015. And the average share of LDC export in global economy between 2009 and 2016 was only 0.91 percent (UNCTAD, 2018). Without a successful multilateral progressive trade liberalisation regime, global trade cannot recover post-recession flows, and objectives like export expansion from LDCs cannot be achieved.

Against these backdrops, Bangladesh will now have to look for the practical options in securing valuable national interest. While the country cannot single-handedly control multilateral landscape, there are valid scopes for playing a proactive role in global leadership. Instead of traditional policies, medium- to long-term negotiation stances from the position of a developing country will have to be devised. Bangladesh may be required to actively engage in the negotiations by forming coalitions with other graduating LDCs or non-LDC developing countries in various areas of interests. On the contrary, Bangladesh will also have to catch up with the advanced and tactically strong emerging economies by actively engaging in regional or bilateral free trade agreements because in the best case scenario, it will take several years for the standstill of multilateralism to give meaningful outcomes. In the meantime, Bangladesh must ensure a strong footing in global market by strengthening exports and securing favourable terms of business with prominent partners.

The Government of Bangladesh has received proposals for potential bilateral trade arrangements from several countries including China, Malaysia and Thailand in recent years. Some analysts suggest that under current unorthodox protectionist approaches by US and some European governments to trade negotiations, Bangladesh would be an attractive country for a potential bilateral deal. Post-LDC Bangladesh may have to negotiate a trading arrangement with the European Union (EU) along with the possibility of an FTA with the post-Brexit United Kingdom. But as it stands today, Bangladesh neither has adequate capacities nor experience for strong trade negotiations and signing comprehensive FTAs.

Industry and trade under the fourth industrial revolution

Fourth of a five-part series titled “Post-graduation globalisation trends and challenges for Bangladesh”

Shamsul Alam | June 18, 2019

As Bangladesh is set to graduate out of the Least Developed Country (LDC) status, a global-scale fourth industrial revolution powered by cutting-edge technology is also on the horizon. As 21st century world prepares for a new age economic transformation, mechanisation or automation has arrived as a credible problem for job creation that requires preparation. Previously what was thought to be simple “creative destruction” or “process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionises the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one”, is now showing signs of emerging with sheer magnitude, thereby disrupting the predictable trends of global economic output and livelihoods. Automation happens to be one of those issues that just might arise as an obstacle in path of achieving inclusive growth and beyond. And like any other country of the world, Bangladesh needs to be cautious and well-prepared about approaching this future.

Technology has dramatically altered what it means for many people to work. But at times, technological advancement also comes with automation. And its price: the many people whose livelihoods will be disrupted or destroyed by it. But the phenomenon of automation is nothing new to the world. Notable previous impact goes back to 19th century when handloom and other jobs of British textile workers were replaced by mechanised production. Innovations in production line automated many industrialised jobs during the boom of roaring 1920’s. In that sense, automation has been a part of economic production that comes with technological advancement. But automation in new millennium comes with a completely different twist. Jointly with rise of artificial intelligence (AI), developments made in machine learning process and availability of industrial robots make the new waves of automation completely different from anything the world has ever experienced. While automation will result in more efficiency, faster production, lower costs, increased outputs and is meant to make life easier for people by completing mundane and repeated tasks, its absolute ability to displace human jobs across manufacturing, agriculture and service sector poses unprecedented threat for global employment levels.

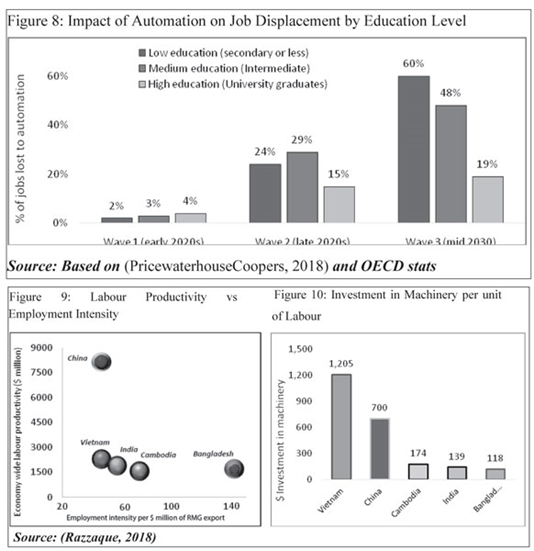

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers’ (PwC) estimations, job displacement, or automation is likely to impact economies around the world in three phases. The first stage, termed as algorithm wave, has already started in developed economies. Powered by high functioning algorithms, simple digitalised tasks will be automated first. The financial, professional and technical services, and information and communications sectors are likely to be the most affected in this phase. The second phase of augmentation wave is likely to start by the end of next decade when repeated tasks in manufacturing, service and agriculture will be taken up by machines. And the third phase of autonomous wave will start in 2030’s. Use of AI and robotics is going to be widespread during this phase. With driverless transports, self-checkout counters, and completely automated factories becoming more omnipresent around this time, chances are that more than half of traditional jobs will be destroyed for good. According to recent research by the McKinsey Global Institute, up to 800 million workers globally will lose their jobs by 2030, to be replaced by robotic automation.

It is important to note that the impact of automation is likely to be different for gender and educational backgrounds. In first two phases of automation, women are likely to be hit harder. In the algorithm and augmented phase, jobs that are considered female friendly, such as repeated tasks in service or manufacturing sector will be replaced quickly. By the third phase, impact will be wider, affecting all major fields and professions in the economy. Jobs that are traditionally held by men will be affected more in the third phase. For educational background, staying relevant to the new innovations will be important to alter impacts of automation. But it does not guarantee an employment when machines take over. By the augmentation and autonomy stages, groups of people with low education will be hit harder (Figure 8). Close to 60 per cent of jobs held by low-educated groups may not survive till the third phase.

University graduates, and especially graduates from science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, are more likely to remain protected. Technological development will also result in the generation of a plethora of new jobs and novel professions. It is now quite clearly understood that commercialised use of machines will focus on displacing jobs where robots will have comparative advantage over human beings. But many jobs will require experts for maintaining or overseeing these machines. While jobs like elementary school teaching, health professionals for growing populations, therapists, social workers, strategists and jobs requiring empathy and creativity will be more powerful than they are now. But again, these jobs and new professions are likely to have an unequal distribution based on educational background.

DEFEMINISATION OF THE MANUFACTURING LABOUR FORCE: Bangladesh’s economy is also showing signs of the first stage of automation. The defeminisation of the manufacturing labour force is currently ongoing. The apparel industry in Bangladesh was marked by spectacular rise in the share of female wage-workers in the formal manufacturing sector. For quite a while, it was widely considered that women constituted around 80 per cent of RMG workers. According to the (LFS) labour force survey (2017), the female shares of employment in the sector fell from 57 per cent in 2013 to 46 per cent in 2016. This is in line with the findings of economists Sheba Tejani and William Milberg, who pointed to a global defeminisation process as a result of industrial upgrading. Their research shows that capital intensity in production, as evidenced by shifts in labour productivity, is negatively and significantly related to shifts in the female share of employment in manufacturing.

As things stand, Bangladesh needs to generate 2.0 million jobs every year to accommodate new entrants to its labour force. Close to 40 per cent of the workforce is still in agriculture, whose contribution to the gross domestic product (GDP) is only 15 per cent and shrinking. Underemployment and youth unemployment are already major issues in the country, with close to 29 per cent of youth being NEET (not in employment, education or training). These mean, non-farm activities will also have to absorb the influx of labour from agriculture. Productivity growth and a rise in the formalisation of informal activities may exert further pressure on the labour market situation. In a context where the 7th Five Year Plan has set a target of increasing the sector’s share in total employment from 15 per cent to 20 per cent by 2020, emerging evidences suggest manufacturing growth and employment generation are not going hand-in-hand for Bangladesh. Between 2013-17, while adding more than Tk 648 billion-worth of output (in real terms using 2005-2006 prices), employment in manufacturing sector was increased by a mere 0.3 million according to LFS (2017).

STAGNANCY OF MANUFACTURING EMPLOYMENT: The stagnancy of manufacturing employment becomes more evident when we look at the RMG sector. During 2010-2018, the sector saw a staggering 144 per cent growth in export earnings (from $12.5 billion to $30.61 billion). But during the same period, growth in employment generation in the sector was only 11 per cent. This slowdown of employment generation happened as local workers became more productive, and producers invested in capital intensive technologies. In the early 1990s, a million-dollar apparel exporting organisation would require on average 545 workers. While in 2016, it has come down to 142.

Although this is not good news for the unemployment issue as it’s suggesting a fall in labour absorption capacity of the sector, this change was inevitable in many respects. Without investing in capital-intensive machineries and becoming more reliant on automation (i.e. sewing bots, mechanised production line), Bangladeshi exporters will never become competitive in the international market. Comparators of Bangladesh, such as China (48), Viet Nam (48), India (59) and Cambodia (75) are far ahead in terms of lower employment intensity or number of workers per million of exported goods. Apart from Cambodia, all these countries have better economy-wide labour productivity than Bangladesh (Figure 9).

This is not to say that Bangladeshi producers should get rid of workers. It means as export production technologies across countries seem to converge, for Bangladesh there exists enormous scope to improve labour productivity driven by more technology-intensive and labour-saving production processes. In 2016, investment in machinery per unit of labour was the lowest in Bangladesh among the major apparel exporters (only $118). Compared to Bangladesh, Viet Nam ($1205), China ($700) were miles ahead; while Cambodia ($174) and India ($139) were slightly ahead (Figure 10). If flagship sector of Bangladesh’s export is going to remain competitive in the global market, moving in the direction of comparators is perhaps unavoidable, which will further suppress its employment generation potential per unit of export.

TACKLING THE ISSUE OF AUTOMATION: Among the post-graduation challenges faced by Bangladesh, automation is perhaps the most challenging one in nature. With correct direction and planning, there is an opportunity to tackle this issue. Moreover, by managing necessary institutional transformation in changing the conventional ways of developing human capital, Bangladesh can stay well ahead of the curve by the time automation affects all industries. Some strong and revolutionary steps need to be undertaken to resolve an issue which is unprecedented in every aspect. Here are some suggestions:

* To remain consistent with the job creation targets of the 7th Five Year Plan, it is extremely important to realise a rapid expansion of exports through export diversification. Given the trends in production technologies, export diversification is perhaps now more important than ever before. Automation will affect all labour intensive exports, but an expanded range of production activities has the potential to generate new jobs.

* Automation is inevitable, and there should be no policy hesitancy about promoting competitiveness by supporting technological upgradation, particularly for export sectors. In some cases, technological advancement can lead to improvements in product quality with prospects for export expansion.

* Non-export and import-competing sectors also need to embrace more capital-intensive production techniques. Investment in machinery and equipment, as measured by import data, per unit of labour is much lower in Bangladesh, compared to Cambodia, Viet Nam or China.

* Despite ominous forecasts of employment generation, automation can open a new horizon of fast economic growth. Rapid manufacturing expansion can fuel this growth and create large number of employment opportunities. Therefore, automation can turn into an opportunity to augment growth. Bangladesh must materialise this window by persistently hitting double digit growth rates (above 10 per cent) per year. Small and medium enterprises, which are critical for livelihood generation, will need support to obtain better access to technology so they can raise their productivity and competitiveness.

* In many ways, the bigger question is not “will there be enough jobs in future?”, but “will there be enough job for workers with the current skill sets in future?” Automation is likely to erode many conventional professions, or change the objectives of same professionals in future. The importance of updated curriculum in education and training cannot be overemphasised. Adapting with the forces of creative destruction requires future generations to be equipped with adequate education. In all levels of education, mandatory quantitative literacy, computing skills and basic STEM courses will become a necessity. As technological advancement will make many skills redundant in quick succession, norms like life-long educational and skill-development practices must be cultured in private-sectors.

* Transforming the social sectors to generate productive employment is another critical policy area. As investment in health, education and public social services remains low, quality of these services is widely perceived to be far from satisfactory. Careful policy attention to these sectors is a necessity in generating future jobs and developing the human capital needed to support socially coherent technological progress.

* Automation will lead to higher inequality with certain groups of people becoming significantly worse off in the process. Potential impact on women and low-education groups must be addressed with necessary government interventions. Policies focusing on training, education and social security of displaced workers will have to be dealt with utmost priority, while progressive taxation will help to ease the rising inequality.

* Future trade policies of Bangladesh need careful evaluation. There will be temptations and political-economic interests to shield the domestic economy from import competition, capital-deepening and technological upgradation. But an excessively protected environment could lead to mounting inefficiencies, with adverse welfare consequences.

* Finally, to enable informed policy-making, there is an exigency for comprehensive research based on quality data. Potential impact assessment of automation across industries of Bangladesh is relatively new and a less explored subject. Without the availability of timely, appropriate-robust data and quality research, it will not be possible to understand the complex interactions involved in labour market dynamism, capture potential changes brought about by technological changes and suggest required policy interventions to respond to those impacts.

Smooth graduation: Learning from experiences of former LDCs

Fifth of a five-part series titled “Post-graduation globalisation trends and challenges for Bangladesh”

Shamsul Alam | Published: June 19, 2019

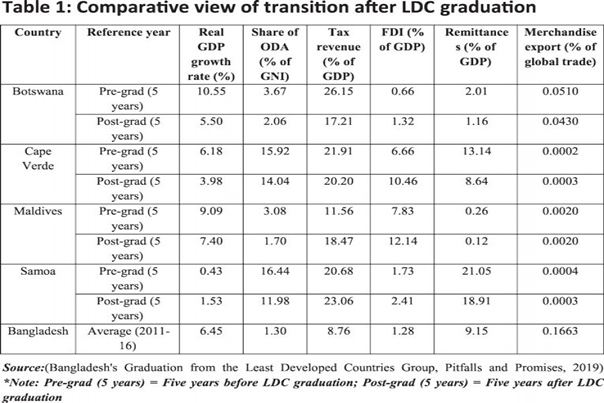

Only five countries have managed to graduate out of the ‘Least Developed Country’ (LDC) status and became ‘Other Developing Countries’ since the formation of LDC group in 1971. However, in terms of economic structure, these countries are quite different from Bangladesh. Among these graduated former LDCs, Cape Verde, and Samoa fall into the category of small island developing states (SIDS). While Botswana and Equatorial Guinea are countries with abundant natural resources, Equatorial Guinea is the only country to graduate under income only criterion, while the rest of the countries matched two criteria of gross national income (GNI) per capita and Human Assets Index (HAI). All countries had weaker than desirable scores in Economic Vulnerability Index. Compared to these countries, Bangladesh is a country with huge population. It is not dependent on natural resources and met graduation thresholds for all three criteria. Therefore, in essence, experiences of former LDCs are not going to be extremely helpful in predicting outcomes of post-graduation era. Nonetheless, they can offer several insights about how a country can maintain progress smoothly in after graduating from LDC status.

Table 1 provides a comparative picture of the former LDCs through the transition period (Equatorial Guinea is excluded because it graduated only in mid-2017). If we look at the few primary indicators for these countries five year prior to graduation and five year after graduation, it gives us a good idea about how LDC graduation have shaped their economic performances. A common theme for Botswana, Cape Verde and Maldives during the transition period has been a slowdown of economic growth. In the immediate post-graduation era, Botswana saw its growth cut down by half while Cape Verde by more than a third. Maldives also experienced slow growth- particularly due to the slow performance of the main export items (fish fillets and frozen fish) to key export destination (EU, Japan). Loss of Duty-Free Quota-Free (DFQF) status in the European market created adverse pressure on the Maldivian economy.

Despite a fall in the gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate, Botswana’s mining industry boomed in post-graduation era and the government maintained a high current account surplus and high tax revenue earning owing to successful diamond mining industry. The country is closely integrated with the global trade and cyclical factors are determinants of growth. But overall, the economic performance of the country has been good since graduation.

One issue that has remained historically challenging for Bangladesh is the collection of tax-revenue in terms of GDP. Evidence suggests, during preparation period of graduation, former LDCs had a high starting tax-GDP ratio. And in the post-graduation transition period, they maintained close to 20 per cent tax revenue-GDP ratio. Overall, the tax revenue collection efforts of Bangladesh will need to go up over the years.

An interesting issue that can be learned from former LDCs are share of official development assistance (ODA) with respect to national income and share of foreign direct investment (FDI) against GDP during the transition period. It has been observed that the proportion of ODA falls against income when any country develops. Countries grow more aid independent in post-graduation era. All graduated LDCs have experienced stronger inflow of FDI in the post-graduation era. This has helped them to recover from early loss of preferential access.

Apart from Cape Verde, all the other four countries had a three-year grace period for preferential access, International Support Measures (ISMs) and other LDC-specific preferences. Cape Verde undertook good planning prior to graduation. The country successfully negotiated with European Union (EU) for additional two-year grace period for ‘Everything But Arms’ (EBA) above the original three-year grace period, and some other transition period deals with prominent trade partners like China (Bhattacharya & Khan, 2019). Malaysia and Botswana have also planned about potential negative impact of graduation. It can be noted, only EU and Turkey have an explicit policy for extending LDC-specific trade preferences for a transition period, the same is not necessarily true for other countries offering unilateral trade preferences (UNCTAD, 2016). For example, there are no smooth transition provisions in case of Japan’s or Canada’s Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) scheme. Therefore, one option for Bangladesh is to start planning for the future ahead and negotiate for transition period preferential access, with options for post-graduation trade deals or free-trade agreements with countries of interest.

From the perspective of Bangladesh, remittance earning has always been a matter of key interest. A strong remittance inflow helps to develop good reserve of foreign currencies, which provides significant leverage to central banks in maintaining favourable exchange rates. Small island nations and land-locked LDCs also substantially rely on remittance inflow due to lack of mature exporting sectors. Former LDCs also face problems like unemployment, underemployment, automation and inadequate working opportunities. Consequently, they resorted to exportation of manpower. As a result, their remittance inflow almost doubled as share of GDP in years following graduation. Bangladesh also needs to emphasise on maximising the migration opportunities to ensure a higher remittance inflow.

It is essential to remember that all countries are different and likely to have their distinct versions of post-graduation challenges. But a common theme for any graduating country will be loss of trade preferences. Experience of former LDCs show why it is important to concentrate on building capacity of domestic industries and develop infrastructures to overcome headwinds of higher integration into the more competitive, global economy.

Importantly, Bangladesh is much better advanced on the development path. Bangladesh has a highly-diversified economy with huge domestic demands for different products. The export performance and remittance inflows are substantial. It has a buoyant private sector with strong entrepreneurial skills. The social fabric is dynamic. The formation of human capital has taken roots. Therefore, with further policy reforms and investments in human capital, technology and institutions, Bangladesh can transit smoothly from LDC to the road of upper middle income country.