“A nation that kills its systems to serve power doesn’t survive; it only reuses the same failure.” — Anonymous

Ever since its birth in sacrifice and bloodshed, Bangladesh needed leadership above expediency, enmity, and ego—a leadership of vision, integrity, and people’s service. Transient moments of such a leadership appeared under President Ziaur Rahman, who advocated institutional strength, national sovereignty, and an unselfish, disciplined, and self-reliant future. But what followed is decades of betrayal.

Dynastic politics, deep-seated corruption, and authoritarian entrenchment were the rule and not the exception. The two principal parties—Awami League (AL) and Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)—took turns to entrench, instead of to govern. The last 15 years of Sheikh Hasina’s rule were a disastrous downfall: extrajudicial killings, bulk surveillance, judicial manipulation, and opposition smothering by terror and violence. The state became a tool of tyranny, and not a servant of its citizens.

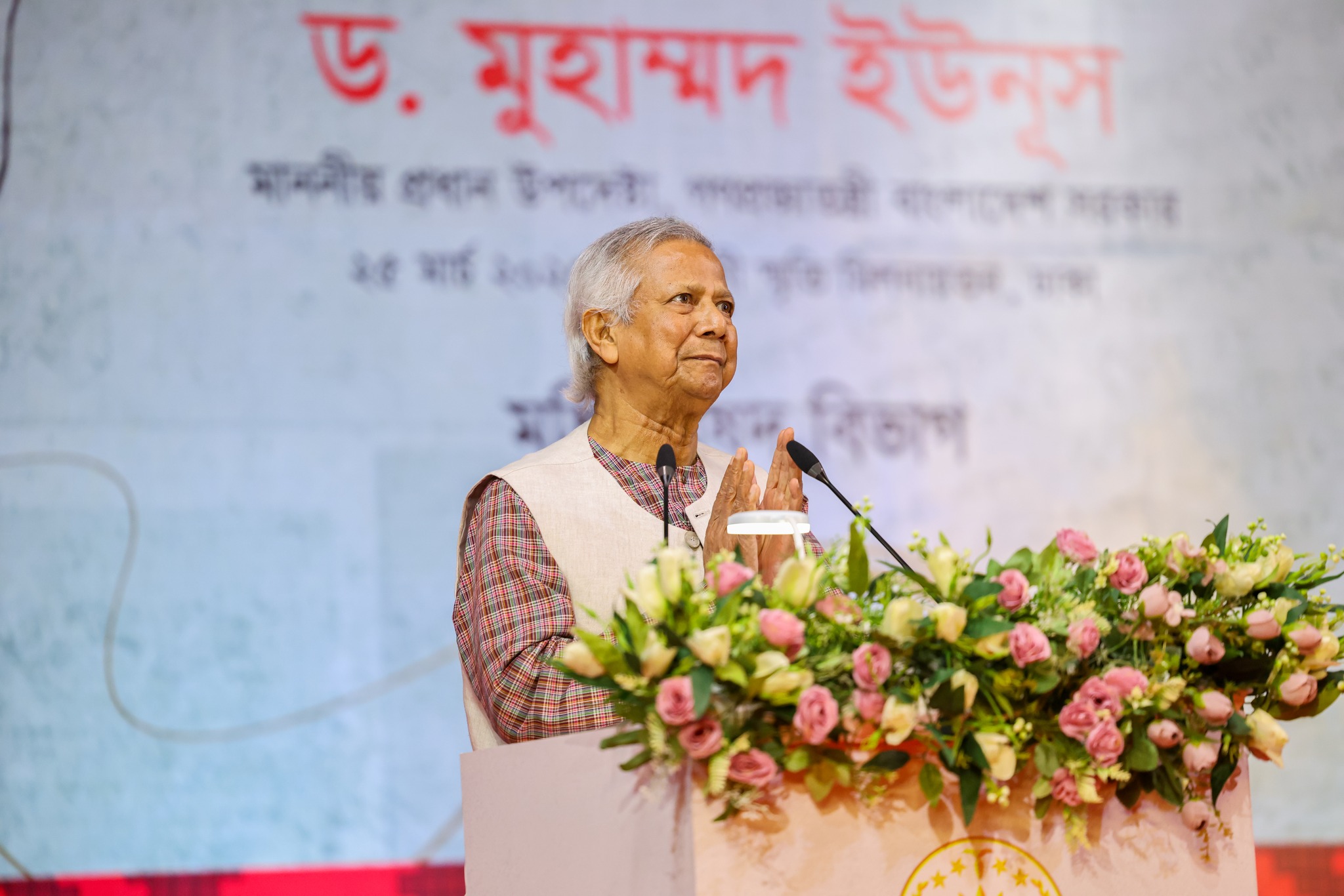

And from the long, bitter night of failure came a flash and surprise beacon of hope: Professor Muhammad Yunus. A Nobel Peace Laureate renowned across the globe as the architect of microcredit and champion of social business, Dr. Yunus was called not a politician but a statesman—one who was not tainted by the disease of partisan warfare. His appointment to lead the interim government after the July 2024 Monsoon Revolution was not an act of administration—it was a symbol. For the first time in generations, the country saw the hope of reform that was principled.

This article examines the mounting pressure for December 2025 early elections and why those calls risk destroying the revolutionary promise of change. It argues that actual democracy cannot be equated to voting ease. It must be built upon accountability, justice, and institutional reform foundations. The revolution was not a matter of changing power—it was about transforming it. And that transformation is still ongoing.

The Yunus Doctrine: Reform Before Elections

Dr. Yunus entered the office to reform, not to rule. Unconcerned with personal power, he pledged to get rid of the partisan obsession that had tainted the state institutions for decades. His mission is to make Bangladesh’s elections cease to be rigged rituals and rather be a true expression of the people’s democratic will.

His government’s emphasis is not power aggregation but institutional purification and system rejuvenation. In a matter of months, the interim government led by Dr. Yunus has:

- Stabilized foreign exchange reserves, halting a precipitous fall inherited from the old regime.

- Raised monthly food rations for more than one million Rohingya refugees from $7 to $12, in synchronization with the United Nations.

- Become a signatory to the International Convention Against Enforced Disappearances, becoming the 75th nation to officially spurn this instrument of authoritarian oppression.

- Enabled a 15% increase in exports year-on-year, driven by the RMG sector and the return of foreign investor confidence.

- Directed record remittance inflows—posting an all-time high in country history.

- Cut annual border killings, averaging 577 in recent years, to only 10 in seven months—through intensified diplomatic protocols and border accords.

- Installed mandatory public asset disclosure by all top bureaucrats and political appointees.

- Installed e-court systems and initiated a mechanism for auditing the judiciary to oversee the disposal of cases and eliminate delays.

But beyond the measurable successes, Dr. Yunus’s most significant contribution has been intangible: restoring the public’s faith in the possibility of honest government. For the first time in years, citizens are being heard. They see a government that serves not a party, but people.

Dr. Yunus’s vision is one of moral leadership and openness. As he himself has consistently asserted, “We were born with the ability to build the world we wish to live in. But for that, we need to first have the courage to clean what has been soiled.”

What is unfolding in Bangladesh is not simply a transfer of power—it is a reorientation of national direction. And it is that clear-eyed objectivity, not populist rhetoric, that defines the Yunus Doctrine.

The Election Puzzle: Why December 2025 Is Too Soon

Despite these reforms, there is a growing chorus demanding national elections by December 2025. This demand is being made not just by domestic political players like the BNP but also by external players—the Indian government, the Indian Army Chief, and even the Bangladesh military generals.

The synchronized nature of these calls raises very strong suspicions about their intent. This call for early elections is actually less democratic and more a motivation to shut down the reform process. For all vested interests, a prolonged transitional period under Dr. Yunus jeopardizes the status quo:

- The BNP, in its desperation to get back into power, sees the present reforms as threatening the patronage networks that underlie its own future electoral relevance. Their attempt at elections is not an aspiration to bring back democracy to the people, but to regain increasingly constricted political space under meritocratic domination.

- The armed forces, ever used to exercising behind-the-scenes control, seem reluctant to forgo its unofficial control over the political process. No public word from senior military officers and carefully crafted political initiatives on their part indicate a desire for controlled transitions rather than genuine accountability.

- India, which enjoyed record-level influence under Hasina’s administration—purchasing ports, trade routes, transit corridors, and infrastructure contracts—does not wish to lose any strategic leverage in an autonomous, re-balanced Bangladesh. Pre-emptive elections give New Delhi the mechanism of re-calibrating influence by supporting a friendly or pliable regime.

Dr. Yunus has already committed to holding elections by June 2026, allowing time for bringing about structural changes. To bring elections forward from that period would be to attempt the very same flawed procedure the revolution was fighting to uproot. A democracy cannot be founded on crisis timetables if it is to thrive. Before any election, Bangladesh requires:

- A reformed and independent Election Commission.

- A judiciary free of political influence.

- Anti-corruption institutions to vet candidates and shield public institutions.

- Restoration of civil liberties, including a free press and political assembly.

- Police and administrative neutrality in electoral monitoring.

- A publicly audited voter roll and secured electronic polling mechanism.

Elections conducted without these safeguards would not represent democratic will but instead be played out as a reversion to electoral authoritarianism. The July Revolution was fought for superficial change—it was a demand for structural change.

As Nelson Mandela once advised, “There is no easy walk to freedom anywhere.” Real reform is never hasty. It requires time, commitment, and ethical determination. Bangladesh has waited for decades for democratic redemption—it must now be given the time and space to do it properly.

Civil-Military Tensions: A Democratic Transition at Risk

One of the emerging issues in Bangladesh’s tenuous democratic transition is the more assertive role of the military—specifically the stance of Army Chief General Waker Uz Zaman. His joining calls for an election by December 2025, which are also being echoed by Indian defense representatives and political supporters of the former regime, has raised questions as to whether the military is remaining neutral in the transitional process.

Actions by General Waker have gone beyond military professionalism. He has been openly at odds with civilian-led foreign policy initiatives, including the proposed humanitarian corridor into Myanmar’s Rakhine State—a endeavor to help displaced Rohingya communities. Calling the program a “bloody corridor,” he vetoed a humanitarian mission on grounds of nationalism, which suggests that the military is insisting on veto power over consequential issues that are within the domain of the civilian arena.

Also, his insistence on being consulted on administrative, legal, and election policy issues reflects an unacceptable encroachment on the governing process. This has shocked civil society and reformist leadership alike, particularly against the backdrop of the military’s earlier role in engineering authoritarian rule during Sheikh Hasina’s regime.

Professor Yunus, an avowed non-politician, has been unbending in the face of such pressure. His principled leadership rooted in international legitimacy and moral imperative has remained steadfast on the reform road. In a recent public address, he said, “Justice delayed is not only justice denied—it is democracy denied.”

His refusal to compromise with vested interests has won him massive popular support but made him a target for powerful players who have a stake in maintaining the status quo. To some, the struggle between the Yunus regime and a politicized military apparatus now represents the struggle of definition over whether Bangladesh can ultimately become an authentic democracy—or slide back to the fiction of electoral authoritarianism.

BNP Reversion to Old Pragmatism

The BNP early on joined the cause of revolution for justice, transparency, and accountability. Its new direction is, however, a return to old pragmatism in politics. While the party continues to be active in reform commissions, its more vociferous calls for an early election—and its unfounded allegations that Dr. Yunus seeks to grab power—betray a calculated turnaround.

More alarming are accounts that BNP activists, in recently vacated bastions of the Awami League patronage machine, have resumed extortion scams against small businesses, the informal economy, and local NGOs. Internal conflicts between BNP factions have flared, with at least a dozen killings of BNP activists in gangland shootouts over access to local fiefdoms.

Their resistance to root changes—like Prime Ministerial term limits, independent watchdog bodies, and constitutional pluralism’s entrenchment—accuses a deeper motivation. Instead of eliminating the autocratic tools they originally lamented, the BNP appears likely to inherit them.

This retreating not only disgusts the youth and civic forces that drove the revolution but also erodes popular trust in mainstream party politics. The revolution was not about changing faces, it was about changing the rules. In fact, latest opinion polls conducted on social networking websites, university campuses, and public forums reveal that as much as 85% to 90% support Dr. Yunus’s reform-first approach. The polls reflect a sea change in public perception: citizens no longer view elections as a panacea but as a system that must be reformed so that it could be more accountable and transparent.

Taxis in Dhaka, garment factory workers in Gazipur, students in Rajshahi, and Gulf remittance workers alike all chant the same slogan: “We don’t want another recycled regime. Let him finish the job first.” Professors, civil society activists, and small business leaders have all spoken out more and more that elections without reform would be to betray the revolution. From across the board and from across the country, it is agreed—reform before the vote.

This increase in support for Dr. Yunus is not due to propaganda or partisanship, but performance. He has restored dignity to government, carried out large-scale public consultations, and focused on institution-building rather than political maneuvering. The calls for early elections are therefore not just premature—they are essentially out of step with the aspirations of the people.

A New Political Consciousness: Gen Z and Civic Platforms

It is at the center of Bangladesh’s transformation that there is a mass movement of political awareness fueled by youth. Movements like Students Against Discrimination and the broader Jatiyo Nagorik Committee were instrumental in mobilizing mass opposition to the Hasina regime. They did not issue party agenda: they insisted on dignity, accountability, and democratic reformation.

These formations, imagined in the heat of protest and forged through their civic engagement, now constitute a new moral axis to Bangladesh’s politics. They are said to have the potential to become an institutionalized political entity—that is, one capable of competing with entrenched elites on the basis of integrity rather than identity.

The BNP finds this threatening to its survival—and rightly so. Unlike traditional parties, such platforms are not fettered by dynastic leadership or grievances of yesteryears. They are powered by moral legitimacy and generational imperative. Their vision for Bangladesh is progressive, inclusive, and reformist.

To rush to elections without completing the institutional reforms that these civic movements demanded would be to squander their sacrifice—and to risk the consolidation of power in untested hands or in familiar authoritarian structures. Either outcome would be a disavowal of the commitment of the July Revolution.

If Bangladesh is to realize the people’s democratic aspirations, it must resist the misleading sense of urgency of premature elections and continue on the path of reform. It can only then build a representative, accountable, and inclusive political system.

Strategic Patience: The Way Ahead

Bangladesh needs at this point not speed, but resolve. The interim government must:

- Publicly commit to a poll calendar between January and June 2026.

- Publish a whole-of-government reform agenda with measurable benchmarks of judicial independence, transparent elections, civil service reform, freedom of the press, and police accountability.

- Increase continuous discussion among political parties, civil society, the Election Commission, and foreign observers to attain mass-level consensus and openness.

Global players must support—not subvert—this transformation. Instead of applying coercive leverage to hold premature elections, they must give financial, technical, and diplomatic assistance towards institution-building. India, and others, must refrain from using electoral timetables as tools for geopolitical opportunism. As Professor Yunus rightly noted, “Genuine friendship is not tested when things are easy—but when a nation dares to change.”

Reform is no obstacle to democracy—it’s the key to it. Demanding elections without reform risks reintroducing the same means by which the people of Bangladesh suffered. In the words of George Orwell, “In a time of deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.”

Dr. Yunus’s government has spoken the truth hard, resisted elite pressures, and begun building a new political culture of accountability and service. What it needs now is not pseudo-tight timelines—but strategic patience and steadfast public trust to complete the revolution.

Conclusion: Revolution Must Mean Renewal

The July Revolution was not waged to re-shuffle political actors, but to re-make the political DNA of Bangladesh. It was not a struggle for shallow democracy, but an imperious demand for system renewal—one powerful enough to overthrow the authoritarian structures that choked the nation for decades. To acquiesce to early elections now, under unaltered institutions and non-transparency structures, would be to betray the dream and embolden the same dysfunction that the people overthrew and destroyed.

Bangladesh took half a century to have a democratic awakening. The people endured repression, economic inequality, and political oligopolies. They didn’t struggle in the streets to be returned to the comfortable chasms of patronage politics. As a protester in Chattogram testified, “We didn’t fight to replace masks—we fought to replace the machinery behind them.”

With Professor Muhammad Yunus at the helm, the interim government has not only set a vision for renewal but begun living it. It stabilized the economy, reduced violence, restored international respectability, and initiated structural reforms that were long assumed to be out of reach. Yunus has not governed either by charm or coercion but by principle and performance.

To let this fragile progress be undone by premature elections would not be healthy for democracy would weaken it. Free elections should emerge out of open institutions, an energized citizenry, and a political culture devoted to responsibility, not loyalty.

Bangladesh stands today at the crossroads of change. It can build a future founded on reform or plunge back into recycled authoritarianism. The revolution was not the end—it was the beginning.

As Václav Havel has written, “Hope is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something is worth doing no matter how it turns out.”

Bangladesh has to remain faithful to that hope. The journey will be challenging, but it has to be taken. Let the revolution not only be remembered for courage, but also be respected in its attainment. Let this be the generation not of retreat—but of renaissance.

A true democracy is not merely worth fighting for. It’s worth waiting for.