by B.Z. Khasru 26 August 2019

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is driving the Kashmir train on the wrong track of ultra-nationalism that cost India 25 percent its land and 20 percent of people in 1947. But it’s not yet too late to change the course to find lasting peace and prosperity for all of its people. The nirvana lies in a blueprint that was secretly drafted a decade ago by two former leaders of India and Pakistan but failed to execute it because of their sudden departures from office.

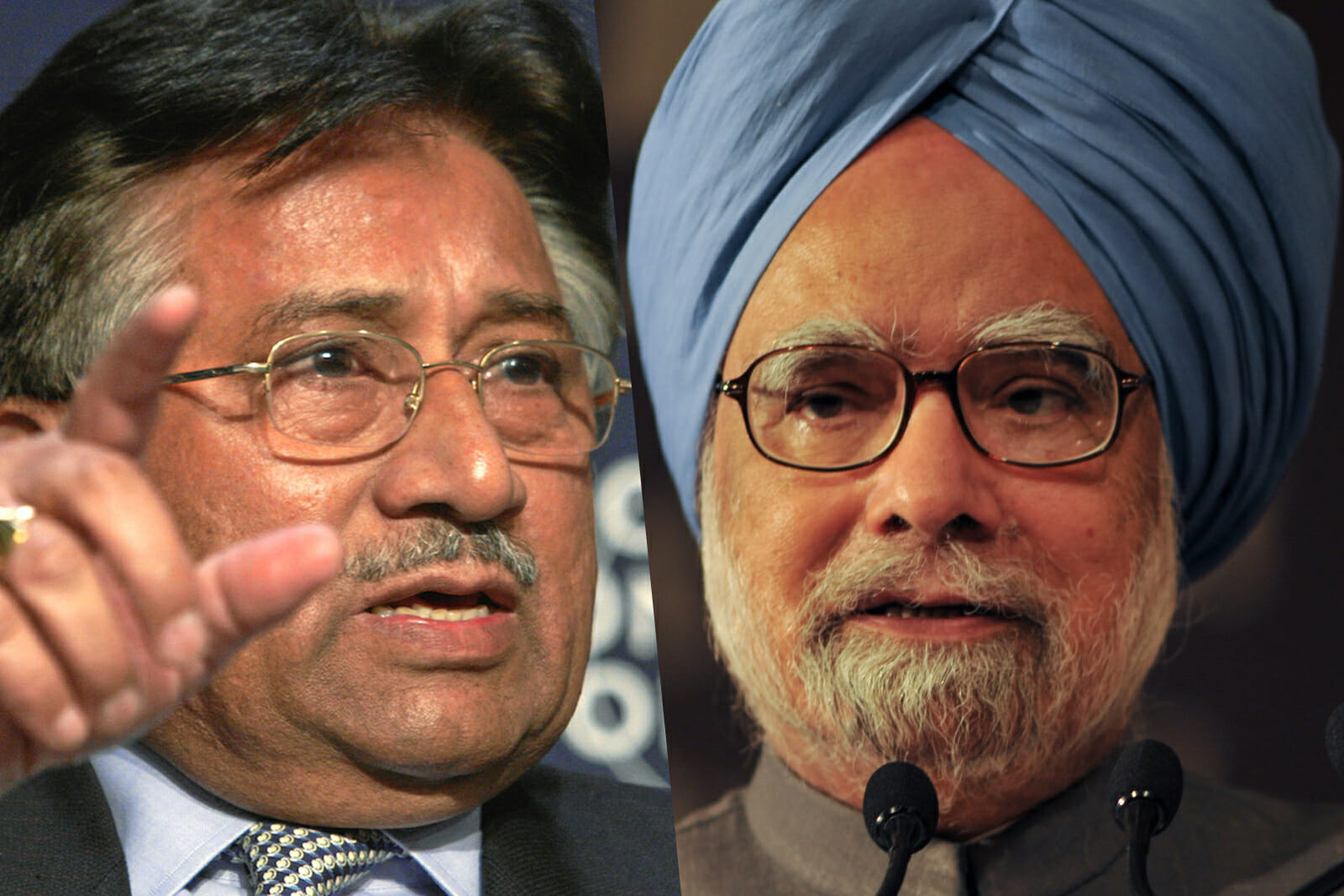

The idea, developed by aides to former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh of India and former President General Pervez Musharraf of Pakistan through backchannel talks from 2004-2007, still remains a viable option to end the seven-decades-old nightmare. This formula is a win-win realistic approach for everyone—India, Pakistan, and Kashmir.

Kashmir, at the center of the dispute between the two nuclear-armed nations in South Asia, encompasses roughly 135,000 square miles, almost the size of Germany, and has a population of about 18 million. India controls 85,000 square miles, Pakistan 33,000 and China 17,000. Both Pakistan and India claim the entire state as their own and have fought two major wars over it since the British left India in 1947.

In 1948, after a fight between the two nations, India brought the Kashmir issue to the UN Security Council, which called for a referendum on the status of the territory. It asked Pakistan to withdraw its troops and India to cut its military presence to a minimum. A ceasefire came into force, but Pakistan refused to pull out its troops. Kashmir has remained partitioned ever since.

The United States has pushed the warring neighbors since the Kennedy administration to make the existing division of the picturesque territory their permanent border, but the idea went nowhere because of a fatal flaw—it gives nothing to the victims of this tragedy, the Kashmiris. India loves the U.S. idea, but Pakistan wants no part of it, and the Kashmiris outright hate it.

Under the Musharraf-Manmohan plan, India and Pakistan would pull out soldiers from Kashmir, Kashmiris would be allowed to move freely across the de facto border; Kashmir would enjoy full internal autonomy; and the three parties—India, Pakistan, and Kashmir—would jointly govern the state for a transitional period. The final status would be negotiated thereafter.

Instead of picking up from where the two leaders left off, Modi has allowed himself to be drugged by a heavy dose of misguided hyper-nationalist vision of the late V.D. Savarkar, who proposed nearly 100 years ago to keep minorities in subjugation in an India ruled by the Hindu majority.

Sitting in a prison cell on the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal, the convicted-violent-revolutionary-turned-nationalist drew up his solution. He would let Muslims and Christians stay in India only if they agreed to be subservient to Hindus; they would not enjoy any special rights that might infringe upon Hindu rights. India today is a nation of 1.3 billion people, with 14 percent Muslim and 2 percent Christian.

Modi ignored Muslim leaders

On Aug. 5, keeping Kashmiri Muslim leaders under house arrest and deploying tens of thousands of soldiers in heavily fortified Kashmir, the prime minister moved to snatch away their special rights— their own flag, own law and property rights—granted by India’s constitution in a blitzkrieg exercise in a matter of hours. By scraping Kashmir’s special autonomy status and dividing the state into two parts, Modi has taken a dangerous step toward implementing Savarkar’s dream.

The fallout from his maneuver will reverberate far beyond India and Pakistan. India’s smaller neighbors, which have historically opposed their Big Brother’s heavy-handed behavior, already see a danger sign in Modi’s action in Kashmir. They wonder how India will deal with them when it will come to settling bilateral disputes. Is Kashmir any indication? It is disconcerting, to say the least, for them to know that the world’s largest democracy has become a mobocracy.

Bangladesh is India’s most friendly neighbor now, and it has enjoyed vastly improved relations with Delhi in recent years. Still, it has concerns about several bilateral matters. One of them is an assertion by Modi’s Nazi-type saffron party that there are 40 million Bangladeshi migrants illegally living in India and that they must be pushed back into Bangladesh. During just-concluded talks in Delhi, Bangladesh flatly rejected India’s claim. The matter was acrimonious enough to force the two sides from issuing a joint communique after the talks ended.

In addition, India is seeking to expand its third-largest Tripura airport on Bangladeshi land. This idea has already faced opposition from a cabinet member, and will certainly run into stiff public resistance. India also is watching China’s move to build a submarine base in Bangladesh. Delhi’s standing policy is to bar Dhaka from granting Beijing a military base on its soil.

Colombo, Modi’s only admirer

India’s other neighbor, Nepal, which often accuses its Big Brother of interfering in its internal affairs, has border disputes, too. To Delhi’s chagrin, China exploits Kathmandu’s displeasure with Delhi by boosting trade with Nepal.

After Modi stripped Kashmir of its special rights, Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, was the only neighbor who openly supported India. He needs India’s help to stay in power. Colombo’s endorsement comes at the expense of its Tamil minority.

Hindu Tamils have close ties with India’s Tamil Nadu state and have faced discrimination from the majority Buddhist Sinhalese, which has intensified since Sri Lanka crushed a separatist Tamil insurgency in 2009. The Tamil rebels, Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, fought for 26 years to create an independent country, Tamil Eelam, in the north and east of Sri Lanka.

Modi’s move has stoked regional tensions within India as well, with some restive ethnic groups seeking autonomy, similar to those granted to Kashmir. One of them is demanding that West Bengal be divided, as Delhi has done with Kashmir, to grant tribal minorities special rights.

On top of all this, the prime minister’s hyper-nationalist campaign in Kashmir will fire-up the already-inflamed fanatical Savarkar disciples to browbeat India’s Muslims and Christians. It will refuel the Islamic extremists in the region and beyond, who will seek to counter Hindu nationalists, making the sectarian conflict even worse. Misguided and unscrupulous Indian politicians are scapegoating minorities as an easy diversionary tactic to camouflage their failure to bring prosperity to their people. India and China had similar per capita incomes in 1960. Today, Indians earn only 25 percent of what the Chinese do.

Musharraf-Manmohan plan viable

Given the region’s history, the M-squared concept offers a realistic solution. It gives the Kashmiris near independence, allows India to maintain sovereignty over Kashmir and lets Pakistan claim it has freed Kashmir from Hindu domination. Compromise is the art of politics, and India must not repeat Pakistan’s mistakes in East Pakistan, which led to a war in 1971. Both India and Pakistan must dig themselves out of the mass hysteria of jingoism they have created during the past 70 years over Kashmir.

Pakistan’s claim over Kashmir is more emotional than material. Pakistan was created based on the concept that Muslim-majority areas of British India would form the Muslim nation. If Pakistan gives up Kashmir, it will void the very ideology that supported its creation and pave the way for its eventual demise, with constituent parts going their own ways. Still, Pakistan has softened its position because it cannot match India’s firepower and take over Kashmir by force; Islamabad now wants a solution that it can sell to the Pakistanis.

India, in the beginning, sought to keep Kashmir in its grip to prove the creation of Pakistan, based on the two-nations theory, was wrong. But over the years India’s mindset has taken a different twist. Now it is driven purely by its hatred of Muslims, principally because of the fact that the Hindus have been subjugated by a gang of Islamic invaders for 1,000 years; the orthodox Hindus think the Muslims have polluted Hindu culture. If the Hindus could, they would wipe out this black spot from the face of Hindustan. Because that is an impossible task, the radical Hindus want to take revenge by driving the Muslims out of India or making them subservient to the Hindus. Those who oppose hyper-nationalism today really don’t matter much, given the religious fanaticism prevailing in the country.

Some Kashmiris, meanwhile, nurture a dream of an independent country of their own. They argue that the Kashmiris alone should decide their fate and that both Pakistan and India must respect their universal right of self-determination. This thinking process ignores India’s security concerns vis-à-vis China, and for this reason, the vision of an independent Kashmir will remain elusive.

The main problem that stands in the way of achieving peace in Kashmir is chauvinism in both India and Pakistan. It has cost tens of thousands of lives and prosperity of both the nations as well as their neighbors. Modi’s extremist party has always opposed a negotiated settlement. It operates on a misguided dream of reuniting the subcontinent into one Hindu nation, if necessary, through violence.

Because of this faulty doctrine, when Singh invited his predecessor, former Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee, to lead the peace talks with Pakistan, he refused. He cited stiff opposition from the Bharatiya Janata Party. The Indians have a hard time to accept a negotiated settlement because they have the notion that Kashmir is already theirs, a notion that has resulted from decades-long, hyper-nationalist propaganda.

Modi’s highly controversial and risky power grab is unlikely to end the crisis. To achieve lasting peace, the M-squared formula should be revived, even though it may be political suicide for anyone who dares doing so, especially in India, where hysteria of Hindu radicalism now reigns supreme. Still, one of the Himalayan gods must make the sacrifice for the sake of the people who have suffered too much for too long.

The article appeared in the International Policy Digest on 25 August 2019