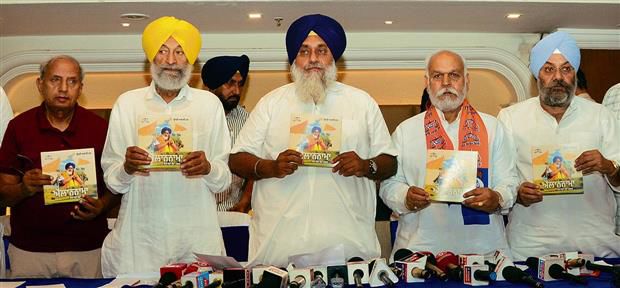

The release of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) poll manifesto has brought to the forefront a familiar yet intricate debate over the territorial integrity and political aspirations of Indian Punjab. SAD chief Sukhbir Singh Badal’s promises to seek the transfer of Kartarpur Sahib from Pakistan to India through a mutual land exchange, alongside renewed efforts to reintegrate Chandigarh and other Punjabi-speaking areas into Punjab, might appeal to some voters. However, these promises divert attention from the underlying issues that Punjab faces—issues rooted not across the border but within the state itself.

Punjab, often celebrated as the land of five rivers and renowned for its fertile fields, today stands as a shadow of its former self. Decades of territorial and political reconfigurations have seen Indian-administered Punjab shrink from a sprawling 202,000 square kilometers in 1966 to roughly a quarter of that size. The creation of Haryana and Himachal Pradesh ceded large swathes of Punjabi land, including 11 districts, to these new states. The jewel in the crown, Chandigarh, was placed under central government administration, further stripping Punjab of its symbolic heart.

This territorial reduction is not merely a matter of geography. It represents a fragmentation of Punjabi culture, a dispersal of its people, and a depletion of its economic and agricultural resources. The fertile lands that once fed the nation are now divided, leaving Punjab with a smaller share to sustain its own population. This historical grievance is compounded by ongoing disputes over water resources with neighboring Haryana.

Punjab claims historical and riparian rights to the waters of the Ravi and Beas rivers, essential for its agricultural economy. However, the construction of the Sutlej-Yamuna Link (SYL) Canal, intended to divert water to Haryana, has been met with fierce opposition from Punjab. The Sikh community fears that the canal would further deplete already limited water resources, pushing the state towards an agricultural crisis. This water dispute highlights the broader issues of resource management and regional equity, which remain unresolved within India’s federal structure.

While SAD’s manifesto addresses emotional and historical grievances, it shifts focus away from the urgent need for internal reforms and sustainable development. The call to reclaim Kartarpur Sahib and reintegrate Chandigarh, though symbolically significant, does little to address the socio-economic challenges plaguing Punjab. Issues such as unemployment, drug addiction, agricultural distress, and inadequate infrastructure require immediate and sustained attention.

Moreover, the manifesto overlooks the potential for constructive engagement with Pakistan beyond territorial claims. The Sikh community in Pakistan is admired for its simplicity, honesty, and bravery—qualities that resonate deeply with the Pakistani populace. The Kartarpur Corridor, a significant initiative allowing Sikh pilgrims from India to visit the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib in Kartarpur, Pakistan, visa-free, exemplifies the potential for positive cross-border relations. This corridor is a symbol of connectivity, goodwill, and strategic foresight, reflecting the deep respect and affection for the Sikh community.

Pakistan’s expansion of the Baba Guru Nanak Darbar shrine from 5 acres to 975 acres underscores its commitment to accommodating religious devotees and fostering goodwill. This expansion is seen not just as a gesture of respect but as a means to strengthen ties between the two communities. By welcoming Sikhs without requiring visas or passports, Pakistan demonstrates its dedication to maintaining an open and friendly relationship.

The idea of a land exchange between the Sikh community and Pakistan, as proposed in the manifesto, misses the broader ambition of establishing Guru Nanak’s land as a free land for Sikhs, ensuring friendly relations between Pakistan and the Sikh community. Similar to Europe, where friendly relations make borders almost irrelevant, Pakistan and a potential Sikh state could enjoy a harmonious and cooperative relationship, benefiting both sides immensely.

However, achieving such a vision requires more than political promises and symbolic gestures. It demands a comprehensive approach to governance that prioritizes the well-being of Punjab’s residents. Strengthening the legal and institutional frameworks to address issues like water rights, agricultural sustainability, and economic development is crucial. Investing in education, healthcare, and infrastructure will provide the foundation for a resilient and prosperous Punjab.

The real challenge lies not in reclaiming lost territories but in reclaiming the promise of a prosperous and equitable Punjab. It lies in fostering an environment where young people can thrive, where farmers have the resources and support they need, and where cultural and historical legacies are preserved and celebrated. This requires a concerted effort from all political stakeholders to move beyond parochial interests and work towards the common good.

In conclusion, while the Shiromani Akali Dal’s manifesto taps into historical grievances and emotional appeals, it falls short of addressing the root causes of Punjab’s current predicament. The real issue lies not across the border but within the state itself. To secure a brighter future for Punjab, a shift in focus towards sustainable development, equitable resource management, and robust governance is essential. Only through such a comprehensive and forward-thinking approach can Punjab truly reclaim its place as a land of prosperity and pride.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published