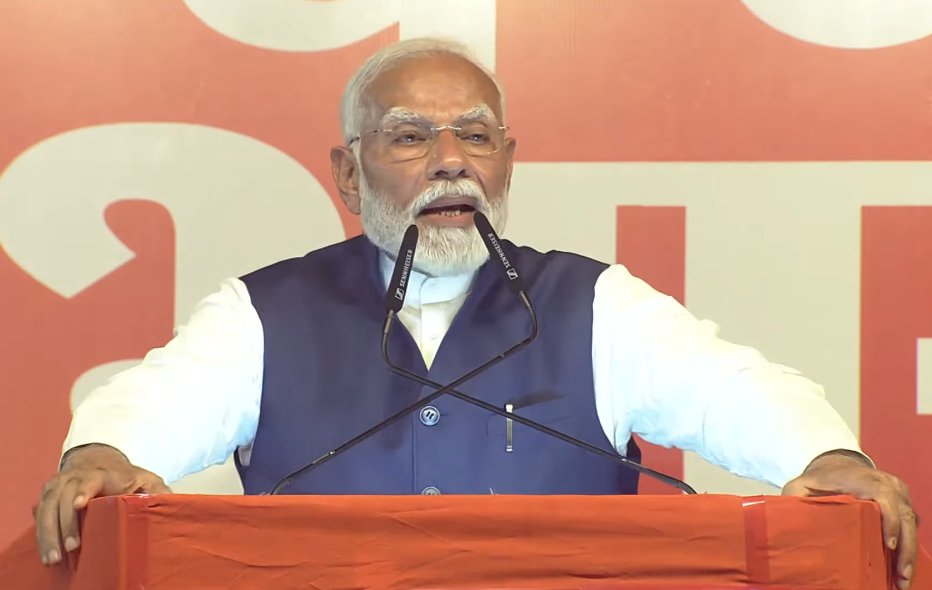

BY: Daniel Markey, Ph.D.Widely expected to cruise to a third-straight majority in India’s parliamentary elections, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) instead lost ground and must now rely on its National Democratic Alliance partners, especially the Janata Dal (United) party and the Telugu Desam Party, to form a coalition government. While the stunning results will have immediate consequences for Modi’s domestic agenda, foreign and national security policies are not top priorities for India’s new parliament. Still, the political changes associated with coalition rule and the BJP’s unanticipated electoral setback could affect India’s international relationships in important ways.

BY: Daniel Markey, Ph.D.Widely expected to cruise to a third-straight majority in India’s parliamentary elections, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) instead lost ground and must now rely on its National Democratic Alliance partners, especially the Janata Dal (United) party and the Telugu Desam Party, to form a coalition government. While the stunning results will have immediate consequences for Modi’s domestic agenda, foreign and national security policies are not top priorities for India’s new parliament. Still, the political changes associated with coalition rule and the BJP’s unanticipated electoral setback could affect India’s international relationships in important ways.

Modi’s New Reality

Modi has never before needed to navigate the trials of coalition rule. He and his party face the unfamiliar, divisive sting of electoral underperformance and political vulnerability. For the moment, India’s electoral outcome has caught everyone off-guard, demonstrating a democratic vitality that some had feared lost in India’s drift toward one-party rule.

Where Does India’ Foreign Policy Go from Here?

India’s elections are never fought primarily over foreign policy, but their outcomes do have consequences. India’s elections affect its policymaking process, the ideology and worldview of its ruling government and the fate of its statesmen.

Throughout most of India’s independent history, parliament — through its debates, committees and even theatrical disruptions — has played an important role in the policymaking process. But from 2014-2024 the BJP’s single-party majority gave Modi the ability to turn parliament into a toothless, rubber stamp body. The operative question going forward is whether his coalition partners will force the BJP back into a semblance of normal parliamentary order. It is conceivable that they will not, instead exercising their power through direct negotiations with the BJP.

However, if normal parliamentary order returns it could complicate some of Modi’s foreign and national security policy projects by, at the very least, exposing them to heated public debate. Some initiatives could get tied up in lengthy political games. Such was the case in 2008 when Congress prime minister Manmohan Singh stared down a vote of no confidence to enact India’s civil-nuclear agreement with the United States. For the BJP, controversial national security initiatives like the “Agnipath” scheme for military recruitment could face new and sustained scrutiny, as would major defense acquisition deals with the United States and other foreign suppliers.

As in the past, budgetary and procurement decisions could become focal points for serious political contestation (often focused on allegations of corruption or mismanagement), largely avoided during Modi’s first two terms. A whiff of political uncertainty will induce even greater than usual aversion to risk by Indian ministers and bureaucrats responsible for signing-off on big deals. That, in turn, would create new obstacles for bold investments in defense or breakthrough trade and investment deals needed to advance Modi’s ambitious agenda on the world stage.

Yet foreign and national security policy are not likely to be the priority issues for a re-energized parliament, and the BJP’s coalition partners are far more concerned about parochial regional and bread-and-butter topics. Moreover, the prime minister’s office does not need much legislation to manage the core activities of diplomacy and national security and has in recent years centralized its hold over the functioning of relevant ministries and agencies, such as India’s intelligence services that report to the prime minister through his national security advisor.

Beyond parliamentary and coalition dynamics, if the Indian public perceives that the BJP’s aura of dominance has been punctured, that alone could begin to reopen space for media, think tanks and academia to pursue investigative and analytical research work that has been increasingly stifled over the past decade. That work spurs and feeds healthy policy debates; it is a necessary piece of the accountability loop between a democratic government and its citizens. Other things equal, a more transparent and accountable foreign policymaking process will also make India a more trustworthy and predictable actor on the world stage. But these changes will almost certainly take time. Or they may not happen at all; many of the BJP’s methods for constraining and influencing public debate will not be rolled back easily.

Modi’s political setback also raises questions about his own fate as India’s chief statesman. Until now, Modi has been the unquestioned face of India; few foreign counterparts would even consider looking over his shoulder to possible successors or playing a long game by cultivating ties with other Indian politicians. That will almost certainly remain true in the near term, but would start to change if Modi shows signs of lame-duck status, if factionalism seriously grips the BJP or if his ruling coalition starts to fray.

Whither U.S.-India Relations?

India’s election outcome will also affect how other states — including the United States — perceive India and Modi. For decades, Washington’s policymakers on both sides of the aisle have framed New Delhi as a natural strategic partner and counterweight to authoritarian China in large part because of India’s democratic credentials. Champions of closer ties with New Delhi, for whom Modi’s authoritarian tendencies had started to become increasingly serious political liabilities, will now tout the very unpredictability of India’s elections and the fact that the BJP has been humbled by India’s voters as evidence that India’s democracy is alive and well. They run a serious risk of overselling that argument, but clearly India’s election result will elicit a bipartisan sigh of relief in Washington, at least temporarily.

On the flip side, Washington and other capitals may soon miss the era of Modi’s political dominance at home, if only because the new reality in New Delhi, while perhaps freer and less repressive, could also be messier and more complicated for U.S. policymakers who have over the past decade gotten used to working directly with a powerful decisionmaker and his top deputies rather than needing to cultivate a wider range of Indian politicians and interest groups. In a worst-case scenario, Modi’s new government could become so consumed with its domestic travails that it lacks sufficient bandwidth to pursue an effective cooperative agenda with the United States.

Modi’s first two terms broke with Indian political tradition in ways large and small; his third will be no different. Yet even if history will be an imperfect guide to navigating New Delhi’s new normal, Washington would be wise to dust off its diplomatic playbooks from prior periods of coalition rule for lessons as India’s unanticipated political drama plays out.

source : usip