30 December 2021

For the first time in the long decades of conflict endured by Afghans since the 1978 communist coup sparked armed rebellion, Afghanistan is largely at peace. And for only the second time in that period, the country is under one unitary authority. This then is a historic moment, but will it last? In the second of two reports looking back at the conflict in 2021, AAN’s Kate Clark analyses how the Republic fell – the role played by the Taleban’s winning strategy and by failures of leadership in Kabul and Washington, and the harm done to civilians. She considers the historical parallels and differences in how the Republic fell and the Taleban’s second Emirate was established with earlier regime changes in an attempt to assess the strength of the new Taleban polity and the dangers it faces as it seeks to secure its rule over Afghanistan.

Image source: Shutterstock

Our first report on the war in Afghanistan this year, Afghanistan’s Conflict in 2021 (1): The Taleban’s sweeping offensive as told by people on the ground, detailed people’s experiences of how their district or provincial capital fell.

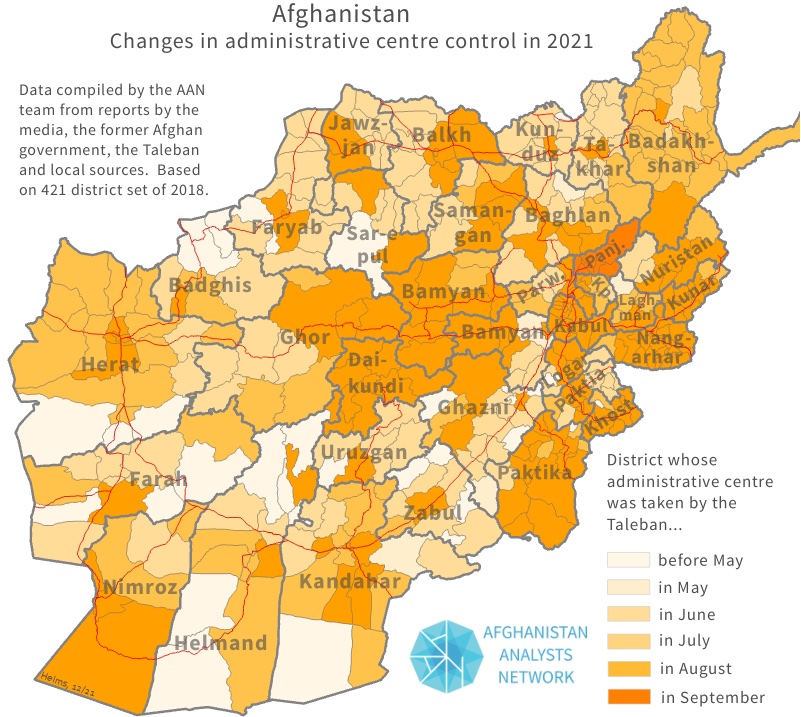

This report showcases maps by Roger Helms which detail when Afghanistan’s districts and provincial capitals fell to the Taleban, based on research carried out by Roger and the AAN team between May and September 2021. His full-size map can be viewed here:

2021 began with territorial control split between insurgents and government, and with the United States mainly keeping its forces out of the war, as it had agreed to do with the Taleban. Then, on 8 April, US president Joe Biden announced that US forces would be withdrawing rapidly and unconditionally, beginning on 1 May and ending before the twentieth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, the event which had brought US forces to Afghanistan in the first place. Biden’s decision catalysed the Taleban into intensifying their fight with the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF). Civilian casualties soared to record levels. After fierce fighting initially, morale on the government side collapsed – as did its hold on territory. In June and July, the Taleban captured district after district, then in nine days, all but one of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces, including eventually the capital on 15 August after President Ashraf Ghani fled the country. The Taleban had crushed lingering armed resistance in Panjshir by the first week of September. As the year draws to an end, only the Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP) is still challenging Taleban rule – at least militarily – and then only in a relatively minor way.

This report is split into three parts. First, it looks at how districts and provincial capitals fell to the Taleban, whether through fighting or negotiations, and tries to map out the harm done to civilians. Secondly, it traces the various roles played by the Republic, the Taleban and Washington in the Taleban victory. Finally, it looks to history to consider how secure the Taleban’s second Emirate may be.

How the Islamic Republic fell: violence and negotiation

On 1 May, when US forces began their final withdrawal, the government held all of Afghanistan’s 34 provincial capitals and all but 31 of its 241 district centres. Control of actual territory, though, was more evenly split;[1] it was not uncommon to find ANSF and officials holed up and isolated in the district centre with the Taleban holding sway outside. What marked out the new phase of the war from May 2021 onwards so distinctly was the Taleban’s decision to try to capture those district centres. They could have tried to seize them en masse before, but had chosen not to until after the US said it was leaving.

For the previous 16 months, the US and Taleban had largely honoured their agreement signed on 29 February 2020 in Doha, which had bound them not to attack each other, but which had allowed the Taleban to continue attacking Afghan government forces. The Americans repeatedly accused the Taleban of breaking unwritten agreements to reduce violence and during that time, the Taleban had appeared to be ramping up attacks gradually and in ways that seemed calculated to see what they could do without attracting a response from the US military, in particular, US airstrikes.[2]After Biden announced the withdrawal, however, there was no longer any brake on the Taleban; they had no incentive to hold back in the hope of gaining more concessions from Washington or out of fear of drawing the US military back into the war. The Taleban also dropped any pretence that they were interested in a negotiated end to the conflict and launched attacks across the country.

Negotiations and surrender played a major role in the Taleban victory which makes it all the more important to stress just how much violence and menace was also involved, and to recall that the Taleban chose to launch this offensive in the middle not only of the pandemic, but also one of the severest droughts in recent years. In the end, the Republic fell quickly, but the offensive might have triggered a fresh round of brutal violence; where there was fighting, neither the Taleban or the ANSF appeared to pay much regard for civilian life and property.

In accounts by local people of how their district centre or provincial capital fell, published by AAN earlier this week, the range of experience is telling. Interviewees describe withdrawals and surrenders that were mediated by elders, or after the ANSF had apparently been ordered to withdraw by their superiors, or had been paid by the Taleban to do so, or after military defeat, including after soldiers had run out of food, water or ammunition. Some interviewees described how they had fled, only to return to bombed or looted homes, while others said they could not afford to flee, or had stayed at home because they were worried about looters. At one end of the spectrum of how Afghans experienced the Taleban takeover was this 70-year old man who lives in Khairkot district of Paktika:

Before the takeover of the district centre, people were afraid there would be fighting, so many left to stay with relatives… In the end, the Taleban took our area without any fighting. The army and the officials just surrendered and handed over their vehicles, Rangers and weapons. The Taleban gave each of them 5,000 afghanis so they could return home. We didn’t hear a single shot being fired. I don’t exactly know why the former security forces and officials didn’t fight. Maybe they were ordered not to from Kabul. I didn’t even realise our area was captured. My sons told me when they came home from their shops.

Others had grimmer experiences, such as this man in Pul-e Khumri who had sent his family to safety and stayed at home alone to look after the property:

… there was fighting for 40 days… I went to my neighbour’s house to take shelter in his basement. A rocket hit my home and destroyed part of a wall. So many buildings were destroyed during the fighting – fuel stations, shops, homes. And many houses belonging to commanders were broken into and looted by unknown people.

For those trapped in the middle of the violence, the consequences could be terrible, as described in this account of fighting in Zakhail, a suburb of Kunduz in June, published by Amnesty International:

[G]overnment forces launched mortars into densely populated civilian neighbourhoods, while Taliban forces gained ground by using schools and mosques to launch attacks, and demanding food from families trapped in their homes. One mortar landed in a home, and a family member rushed a 12-year-old girl, Manizha, to the hospital, a metal piece of frag stuck in her spine. It took her over a week to die of the injury.

Only the accident of fate seemed to lie behind some Afghans seeing their districts fall without bloodshed, while others suffered terrible destruction from airstrikes, rockets and mortars and looting.

An early indication of just how many civilians were killed and injured in the Taleban offensive and ANSF defence came in UNAMA’s 2021 mid-year Protection of Civilians report (AAN analysis here). The year had begun with already unusually high levels of violence. Winter, usually the season when the conflict subsides in Afghanistan, had been unusually violent. The last quarter of 2020 had seen more civilian casualties than the last quarter of any year since UNAMA began systematic reporting in 2009 (UNAMA report here and AAN analysis here). October 2020 had been the worst month of any month that year. As UNAMA noted, as the intra-Afghan talks began in Doha, the violence had ratcheted up.

The first six months of 2021 would then prove as deadly for civilians as the record highs seen in the years 2014 to 2018.[3] Half of all the civilian casualties recorded by UNAMA in the first six months of 2021 occurred in just two months, May and June, ie after the Taleban launched their offensive. UNAMA reported that May 2021 was the most violent May of any year since 2009, and June 2021 the most violent June. It has yet to publish figures for civilian casualties beyond June. However, the conflict carried on at such a fierce level through July and into August that it is difficult to imagine they were lower, or much lower.

The high number of civilians killed and injured in the conflict in 2021 was striking because the war in Afghanistan was then being fought mainly between Afghans. After the US-Taleban February 2020 agreement, which bound the two parties not to attack each other, but allowed the Taleban to attack the ANSF, the US largely removed itself from the battlefield. This spared the Taleban their most dangerous enemy, while denying the Afghan National Security Forces US support except in extremis. It translated into the US taking a much reduced and sporadic part in the war after February 2020.

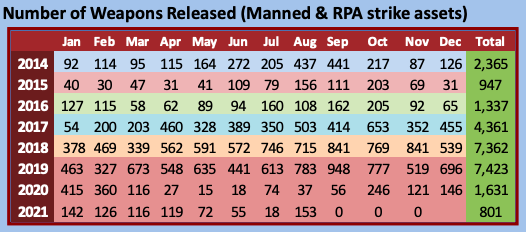

According to the US’s own published statistics, the number of ‘weapons’ dropped by the US air force in 2020 was 1,631 (almost half of the yearly total came in the two months before the Doha agreement was signed), compared to 7,362 in 2018 and 7,423 in 2019, and 801 in 2021 (first eight months only). In the chart below, it can be seen that the number of air munitions fell after February 2020 and rose somewhat in autumn 2020 as the US used airstrikes, for example, to drive back Taleban offensives in the south (see a call by Amnesty International for safe passage for civilians out of Lashkargah in October and Washington Post reporting on Kandahar in November). The number of munitions that the US air force dropped fell again after Biden’s decision to withdraw, rising only in August 2021 as the US air force made last-ditch efforts to shore up the ANSF.[4]

Data from Combined Forces Air Component Commander, from original website: https://www.afcent.af.mil/Portals/82/November%202021%20Airpower%20Summary_FINAL.pdf

The main causes of civilian death and injury during the first six months or 2021, as reported by UNAMA, also says much about the nature of the conflict that year. The most common way for Afghan civilians to be killed or injured was through IEDs laid by insurgents. The first six months of 2021, said UNAMA, were the worst for IED-caused casualties of any January to June on record. Next came deaths and injuries suffered in ground engagements between the Taleban and the ANSF in which women and children comprised two-thirds of the victims. They suffered disproportionately, reported UNAMA, because both sides used mortars and artillery in populated areas where homes provided no protection to those sheltering inside.

The campaign of targeted killings, which were often unclaimed but largely believed to be carried out by the Taleban,[5] that had begun in late 2020, did not let up, but represented the third most likely way for civilians to be injured or killed: UNAMA said the campaign targeted an “ever-widening breadth of types of civilians… human rights defenders, media workers, religious elders, civilian government workers, and humanitarian workers.” The campaign also targeted members of the ANSF. According to one security source in Kabul, twice as many ANSF were targeted and killed or injured as civilians.

Finally, airstrikes, often used in densely-populated areas, killed twice as many civilians in the first six months of 2021 as in the first six months of 2020. UNAMA attributed these casualties “mainly” to the Afghan Air Force, although this has been questioned subsequently, since the US published statistics on weapons dropped (for example, by Airwars which thinks a larger proportion of civilian casualties should be attributed to US airstrikes).

Typically, the fighting that did take place from May to August 2021 was worse in areas close to cities or ANSF bases. The fighting in and around Lashkargah, Kandahar and Sheberghan was particularly fierce. Using explosive weapons in built-up areas, whether rockets and mortars that are difficult to target anyway, or munitions from airstrikes, was bound to kill large numbers of civilians, especially when – as all parties to the conflict appeared to do – they were used recklessly and without regard to the people trying to shelter in their homes. Another statistic indicating the scale of the violence and fear engendered by the conflict in 2021 was the huge number of Afghans forced to flee their homes. OCHA has calculated that almost a million people (986,756) fled because of the conflict between 1 May and mid-September, with the peak of displacement happening in July. [6]

There are no publicly available figures for the number of ANSF and Taleban killed and injured in 2021, but they must surely have died in numbers greater even than civilians.

Continuing violence

The violence this year has not been limited to the fighting itself. Many people reported looting – whether by Taleban or others, it was often not clear. There have also been continuing allegations of killings carried out by Taleban despite the location-specific and general amnesties given to government officials and members of the ANSF. Such killings are now being documented. Amnesty International has published details of killings by Taleban in: Spin Boldak in Kandahar province in July, along with the denial of medical treatment to wounded male civilians and government soldiers; Malestan in Ghazni, also in July, including three men allegedly tortured to death; Khedir district of Daikundi in August, which included the alleged killing of a 17-year old girl and; Panjshir in September, alongside the torture and mistreatment of detainees.

Another report, by Human Rights Watch, ‘No Forgiveness for People Like You’: Executions and Enforced Disappearances in Afghanistan under the Taliban, published on 30 November, focused on the summary execution and forced disappearance of security sector personnel from 15 August up to 31 October.[7] It alleges that requests for security personnel to register for amnesty and hand in their weapons were used to identify and then target them. It also traces the Taleban searching for former personnel who had gone into hiding, “often threatening and abusing family members to reveal the[ir] whereabouts.” As ever in Afghanistan, contacts may offer some protection, as Human Rights Watch notes: “Those executed on the spot often included lower-level security force members who were less well-known or lacked the protection of tribal leaders, especially in the south.”[8]

Nada al-Nashif, United Nations Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights has also said, on 14 December, that they had documented more than 100 Afghans killed since the Taleban took power, including former ANSF personnel, at least 50 men suspected by the Taleban to be members of ISKP, who were beheaded or hanged, at least eight activists and two journalists. The UN, al-Nashif said, was particularly alarmed about the “safety of Afghan judges, prosecutors, and lawyers – particularly women legal professionals.”

The other form of violence suffered by some Afghans in the wake of the Taleban victory has been forced displacement. Human Rights Watch in a press release from 22 October alleged that former officials, as well as Hazara communities, have been targeted. Earlier that month, it said:

… the Taliban and associated militias forcibly evicted hundreds of Hazara families from the southern Helmand province and the northern Balkh province. These followed earlier evictions from Daikundi, Uruzgan, and Kandahar provinces. Since the Taliban came to power in August, the Taliban have told many Hazaras and other residents in these five provinces to leave their homes and farms, in many cases with only a few days’ notice and without any opportunity to present their legal claims to the land.

As the year ended, no group except the Taleban enjoyed any territorial control in Afghanistan. However, there have continued to be occasional attacks, mainly involving small arms, hand grenades or IEDs, against the Taleban. Some attacks have been claimed by ISKP and a few by the National Resistance Front, the group established by former first vice president Amrullah Saleh, and son of the mujahedin commander, Ahmad Shah Massud, Ahmad Massud, which held out for several weeks in the Panjshir. Many attacks, however, are unclaimed and may not be linked to any organised group. Such attacks are far lower in number and generally more minor in scale than those directed by the Taleban at the previous government. As yet, however, they show no signs of fading away.

In Nangrahar, violence has been more systematic and on a larger scale, with assassinations by Taleban and ISKP of each other’s cadre or suspected cadre, and with some suicide attacks by ISKP. The Taleban have also closed down, reported al-Jazeera on 27 September, “more than three dozen Salafist mosques across 16 different provinces.” (Salafism, also known as Wahabism is the school of Islam to which ISKP adheres, along with a sizeable number of non-ISKP-aligned Afghans; most Afghan Sunni Muslims, including the Taleban, are Hanafi.)

The change of regime has had no detectible effect on ISKP’s murderous sectarian campaign against Hazaras. West Kabul has seen no let up in attacks (there were two unclaimed bombings earlier this month on 10 December which had all the hallmarks of ISKP attacks – see press reporting here) and there have also been attacks in territory where ISKP was not known previously to be active: the group sent a suicide bomber into the Sayed Abad mosque in Kunduz, who killed at least 72 on 8 October, and bombed the Bibi Fatima mosque in Kandahar killing at least 63 people on 15 October (see Human Rights Report here).

Why did the Republic fall – failure in Washington, chaos and corruption in Kabul, clear-headed strategy from the Taleban

Washington’s role

Although historical parallels and differences is the subject of the next section of this report, one parallel is highly significant for thinking about why the Republic fell so swiftly and completely. After 1989, when the Soviet army withdrew from Afghanistan, the last government of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) of Dr Najibullah held out against the mujahedin for three years. Its downfall came only in 1992 after Moscow stopped funds. In 2021, the Republic fell even before the last US soldier had left and with large amounts of money still flowing. Some of the difference in resilience surely lies in how the USSR spent its final years in Afghanistan building up the Najibullah regime in contrast to the US, which spent a similar time undermining Ghani’s government and the ANSF and boosting Taleban morale.

The desire of Donald Trump and his envoy, Zalmay Khalilzad, for US troops to leave Afghanistan and to have some sort of deal in place with the Taleban led to Khalilzad agreeing to the Taleban’s demand to exclude Kabul from negotiations, conceding his own much-vaunted determination that nothing should be agreed until everything was agreed (AAN analysis here and here). He then signed what was in effect a withdrawal agreement with the Taleban. The Taleban won the removal of their main enemy from the battlefield, while the US gained very little, only the prospect of being able to withdraw troops safely, a promise of intra-Afghan talks and the vaguest of assurances about the place of al-Qaeda in a future Afghanistan. In the process, the US had also managed to legitimise the Taleban on the world stage (see the text of the agreement and our analysis here).

Subsequently, the US insistence on strengthening the ‘peace process’ led it to undermine the ANSF and Kabul administration and bolster the Taleban yet further. Its moves included forcing Ghani to release 5,000 Taleban prisoners, as the US had agreed with the Taleban he would do. In response to Afghan government protestations, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo even threatened to withhold aid if Ghani refused to comply. After the US-Taleban agreement, the ANSF was also ordered, at America’s insistence, to take, first a posture of defence and then, ‘active defence’ (that is pre-emptive strikes against the Taleban were allowed, but not offensive strikes). These were intended to be confidence-building measures aimed at fostering an atmosphere conducive to talks. AAN guest author, Andrew Quilty, documented in interviews conducted in summer 2020 with members of the ANSF and the Taleban how this strategy helped boost Taleban confidence, while denting morale among government forces:

For the Taleban and their sympathisers, the [February 2020] agreement is seen as a reward for the sacrifices made during the 15-year insurgency. With the threat of being targeted by government or US forces now low, morale among fighters has soared. According to those AAN spoke with, the fight against the United States brought the agreement to withdraw and, in the meantime, to abstain from offensive operations…

Government forces are widely distrustful of American intentions and see the US as having made the Doha agreement in bad faith, with scant regard for the outcome for Afghans themselves. Most of those who spoke to AAN see the agreement as benefitting the US and the Taleban at the expense of the Afghan government and the ANSF, who, they point out, are still dying everyday. Most members of the ANSF that AAN spoke with also expressed frustration over the government’s sudden passivity toward the Taleban. After the severe Taleban losses inflicted by last year’s intense US air campaign and the fear wrought by widespread night raids, Ghani’s orders after Doha—to defend only— have allowed the Taleban unfettered control in areas already under their sway and greater freedom to impose themselves in contested areas, most notably on major roads and highways. To many government and security officials, regardless of whether it might serve the purported goal of peace, the new orders are militarily weak and politically foolish.

When, in April 2021, newly-elected US president Joe Biden announced that US forces would be withdrawn swiftly and unconditionally, it was without even a plan to carry about various key tasks that the ANSF still relied on US personnel for, such as aircraft maintenance. In their withdrawal, the US military appeared to coordinate more with their enemies than their allies – witness the departure of US forces from their main base at Bagram on 6 July when they did not even inform Kabul of their departure, nor leave the lights on (as AP reported).

Gloomy assessments published by parts of the US government focussing on the Republic’s weakness also did not help ANSF morale. “The Taliban is likely to make gains on the battlefield” was the conclusion of the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence, published on 13 April 2020 “[T]he Afghan government will struggle to hold the Taliban at bay if the coalition withdraws support,” it said. Later, on 23 June, US intelligence agencies were predicting that the capital could fall as soon as six months after the US withdrawal (see this, behind a paywall, Wall Street Journal report).

“It is common knowledge in Afghanistan,” we wrote earlier this year, “that many fighters only fight as long as they are paid and as long as they believe they can win.” Ironically, the US military had not played that important a direct role in the conflict for a long time, but their abrupt departure was to have a pivotal role on its outcome. The way the US withdrew left many in the ANSF feeling that no one had their backs. It undermined the ANSF’s belief that they could win while, at the same time, convincing the Taleban that they were heading to victory.

Khalilzad had gambled all on the Taleban genuinely wanting to negotiate. He never had a Plan B of what to do if the insurgents were playing for time and actually intent on military conquest. Bizarrely, he and other US officials clung to their fantasy peace process into August, even as huge swathes of Afghanistan fell to the Taleban.[9]

Kabul’s role

Despite the damaging way Trump and Biden ended the US’s two decades intervention in Afghanistan, a Taleban victory on the battlefield was still not inevitable. For that one must look to the dire failings of Afghan leadership and systemic weaknesses in the Afghan political system and security establishment.

Years of treating government posts as opportunities to make money had particularly afflicted the Ministry of Interior and Afghan National Police (ANP). From the earliest of days, the ANP often seemed to be run as a ‘dual-purpose’ organisation, focussed on security and involved in crime. One study from 2016 looking at the police in Kabul, for example, described the force as characterised by “corrupt, pyramidal networks that engage in racketeering and extortion from the population instead of protecting citizens and enforcing the rule of law.” (See also the author’s in-depth analysis of corruption in the Ministry of Interior and how attempts at reform were successfully resisted for more detail and further sources on this subject).

Demanding money for appointments, setting up crooked contracts, and employing ‘ghosts’, all these practices also plagued the ANP and Ministry of Interior, and to a lesser, but not insignificant extent, the Afghan National Army (ANA) and Ministry of Defence. It has been notable how often problems with supplies – running out of ammunition or food – were mentioned by ANSF as lying behind their inability to defend posts and bases in 2021. On 1 August, just two weeks before the Republic was to fall, it was revealed that the garrison commander of the Zabul garrison had allegedly been selling aviation fuel (press report here). Not being paid was a frequent complaint by those on the ground.

There has been some discussion since the collapse as to whether it was caused by the majority of soldiers and police appearing on the rolls actually being ghosts – fake individuals whose salaries were pocketed by corrupt officials (see, for example, allegations made to AAN by the former minister of finance, Khalid Payenda here). Former acting defence minister Shah Mahmud Miakhel (in post until March 2021) said this had not been the case in the ANA at least. By 2020, he said, all personnel had been enrolled in the Afghan Personnel and Pay System, the computerised system which used biometrics and vetting and salaries paid to individual soldiers’ accounts with money released by the US military to the ministry of Finance each month. “We had no ghost soldiers,” he told AAN. Numbers in the field were always legitimately lower than were on the payroll because, at any one time, approximately 30 per cent of the 180,000 soldiers enrolled were on leave, injured or captured. The exception, he said, were some soldiers whom various commanders were illegally using as bodyguards. The case of the police was different, he said, with only about 60-80 per cent of ANP enrolled in the APPS system, there was more room for ghosts there.

Miakhel, like others that AAN has spoken to, believed that what was fundamental to the ANSF collapse were the multiple leadership changes made in 2021 which weakened the morale and integrity of the security forces, their chains of command and trust, both in the field, and between the field and Kabul, and ultimately morale. In 2021, President Ghani replaced more than half of Afghanistan’s district police chiefs, along with almost all the ANA corps commanders, the chief of the army, and the ministers of defence (once) and interior (twice) (for names and dates see footnote 2 of this AAN report). He also transferred security responsibility for provinces from governors to ANA corps. Miakhel said:

The collapse was not based on numbers [ie ghost ANSF]. It was based on the lack of proper leadership to guide and boost the morale of the rank and file. There was a disconnect in the chain of command and a lack of coordination between security institutions at all levels. If a local commander in the field can’t contact his own leadership, if he gets no response, if he needs air support or direction or coordination at the provincial or district level… Changes of leadership create a vacuum of leadership. This was a big issue behind the takeovers.

That lack of trust, support and leadership within the ANSF featured in some of the accounts of how Afghanistan’s district centres and provincial capitals fell in AAN’s first part of its review of the conflict in 2021, published earlier this week. Several interviewees, we wrote, were left feeling betrayed and bewildered after “decisions by the security leadership in Kabul that had undercut the military units that had still wanted to defend their areas and left them fatally isolated.” Interviewees also reported military units that were “unable, no longer willing or sometimes not even authorised to fight back against the Taleban onslaught.”

According to Miakhel, the repeated hiring and firing of those in leadership positions also created competition and uncertainty among the ANSF command, said:

Unfortunately, whenever there was a problem or setback somewhere, Ashraf Ghani would immediately react by firing someone. Then [the people round him] would try to appoint people based on their connections and loyalties, not after due process. There was also negative competition between [National Security Advisor Hamdullah] Mohib and First Vice President] Amrullah [Saleh]. Each one wanted to have control.

Outside the ANSF, in 2021, there was also much talk of a second resistance – following the first against the Taleban in 1996-2001. Even after twenty years of Afghans seeing the old Northern Alliance leaders making money and enjoying luxurious lives, those leaders might still have been able to rally support if they had been properly resourced. This was not forthcoming. Ghani transferred few resources to those outside the ANSF who wanted to defend the Republic. In the end, resistance against the Taleban was only really seen in Herat lead by Ismael Khan, in Sheberghan by Jombesh militias and after the fall of the Republic in Panjshir by Shura-ye Nizar stalwarts who were joined by some members of the ANSF who formed the National Resistance Front. In both cases – the wholesale changes to the ANSF leadership and dithering over funding resistance groups – it seems probable that Ashraf Ghani was driven by worry over internal threats to his power from coups or factional leaders gaining influence beyond his control, and underestimated the much more real threat coming from the Taleban.

It was not only in the Palace, but also among the political elites of the Republic more broadly, that the Taleban threat engendered far too little sense of urgency. That threat demanded unity and seriousness of purpose if the Republic was to be defended. Yet there seemed little indication from those in power that their action or inaction was helping to foster the fall of the administration. Rather, most carried on as if it was business as usual.

Khalilzad’s strategy had rested on two assumptions, that the Taleban would fear the US military might stay – and therefore enter wholeheartedly into peace talks with Kabul and agree a ceasefire/reduction in violence – and at the same time, that the political elites in Kabul would fear the US military might go – and therefore would put their house in order and push for a negotiated end to the war. In the end, the strategy failed on both counts. The Taleban correctly read US intentions, that they would leave, pretty well, come what may and prepared accordingly. In Kabul, meanwhile, even after the February 2020 agreement which bound the US military to leave Afghanistan in 2021, the elites continued to squabble and fight over resources and jobs. There were the rival presidential inaugurations of March 2020, finally resolved only in May (AAN analysis here), fights over cabinet posts (see this analysis from June 2020) and the seats on the various peace organisations set up to oversee the ‘peace process’ (see this AAN reporting) and even, at the end of June 2001, even as the districts fell, wrangling over would go to Washington to meet President Biden (just Ghani or also Dr Abdullah? And how big should their delegations be?).

The fight over the 1400/2021 budget, which we detailed here, showcased the deep and toxic dysfunction at the heart of the Republic: even as the administration teetered on the edge of a Taleban takeover, those in power were “too busy lining their own pockets and too intoxicated by the prospects of power to notice the wolf at the door.” Is it any wonder then that in so many places the ANSF, demoralised and with poor leadership, seeing those in power living easy lives while they faced a determined enemy wondered at the point of fighting? In the end, the final coup de grâce to the Republic was delivered by the president himself as he opted to run away and flee the country, rather than deal with the Taleban, then at the gates of Kabul. At that point, almost all resistance was over.

The Taleban’s role

In comparison to the chaos and corruption in Kabul and the fantasy peace policy pursued by the Khalilzad and the Trump and Biden administrations, the Taleban played their adversaries well. They strung the US along at Doha, won the departure of their most powerful enemy from the battlefield while making only the most minor of concessions, and prepared for war even as their political cadres spoke of peace. A generation of diplomats who had run out of ideas found it easier to believe Taleban assurances than to question US policy.

After the Biden announcement, the movement first targeted the north, where resistance to the first Emirate had been fiercest and most persistent and where the old factional leaders of the Northern Alliance, or their sons, might lead the much talked-about resistance. In our reporting on the conflict in May and June, we found that half of the districts which fell in those first two months of the Taleban offensive were in this region, as the map above shows.

The Taleban had invested human resources and manpower in the north. Almost all of their local officials and most of their fighters were local men, well aware of the region’s political and geographical dynamics. In some places, outsiders also arrived to reinforce the attack: for example, a ‘red unit’ deployed to Baghlan, and fighters from Badghis and Helmand were sent to strengthen what proved to be critical offensives in Faryab. Three districts there fell only after fierce fighting: Qaisar – a Taleban victory after the detonation of a massive car bomb; Dawlatabad, after the ANP failed to support ANA commandos who had retaken the district centre and who would subsequently be overpowered and killed, apparently as prisoners of war, which would have been war crime and; Shirin Taghab, reportedly after the ANSF had run out of ammunition. After those defeats, morale collapsed and other districts in Faryab fell with little fighting, as they also did in neighbouring Jawzjan. Faryab, known as the ‘Gateway to the North’ as it has proved a key province in the Afghan conflict tilting in earlier phases of the war, was again pivotal in 2021. (See this AAN report for maps and details of how other districts in nine northern provinces had fallen by the end of June.)

The Taleban also targeted locations generating revenue, especially border crossings (see this AAN report from mid-July). This gave new funding streams to the Taleban while weakening the government financially. The movement left the more challenging ‘difficult’ places to the end, including Pashtun-dominated provinces with populations more friendly to the government who might have fought long and hard if they thought the Republic was holding: Nangrahar, Kunar and Khost were among the last provinces to fall.

In every location we looked at in detail, including three stand-alone reports on Paktia, Nimruz and Laghman provinces, their fall showed the impact not only of what was happening at the national level, but also the importance of location-specific factors. Local, often old relationships between members of the ANSF, the Taleban and civilian leaders, of relationships between province and Kabul, and of local leaders’ trust – or lack of it – in the government and in Taleban assurances, all often came to play in how districts and provinces fell, whether violently or through mediation.

The Taleban’s canny use of amnesties and deals, allied with the unremitting threat of violence, successfully weakened the resolve of those in the field. Why fight on if the neighbouring district or province has folded and its soldiers and police allowed or even paid to go home? Many members of Afghanistan’s security forces, demoralised and not trusting their leadership, felt it was foolish or hopeless to fight on, as did many civilian leaders. Whether they actually preferred the Taleban to the Republic appeared to be less pertinent in the end than the wish to spare the ANSF and civilians more violence.

Historical parallels and differences – where the new Taleban regime is strong and where it may prove weak.

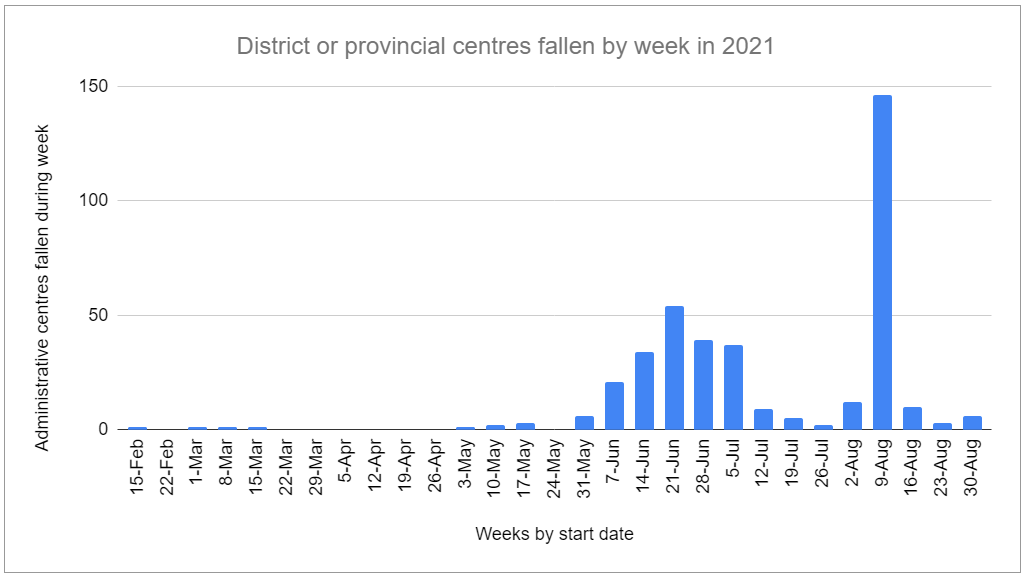

The rapidity of the fall of territory to the Taleban over the summer of 2021, vividly illustrated in the chart below, was typical of the way the Afghan conflict can suddenly shift; when people decide the ‘winning side’ has changed, they respond accordingly. The fall of the Islamic Republic was most reminiscent of the Taleban’s own collapse in 2001. In both cases, it was the weakness of those in government, rather than the strength of those attacking that drove the collapse.

The breakneck speed of the collapse of the Republic in 2021, even as the American military left, was in vivid contrast to how the Najibullah government hung on in the face of the mujahedin for three years from 1989 to 1992 after the Soviet army withdrew. However, the eventual speed and nature of the fall of the Najibullah government also showed striking parallels with the collapse of Ghani’s administration.

In 1992, it was the halt of Russian funds that Najibullah had been using to pay various pro-PDPA militia commanders which catalysed their revolt and break from the centre, and the swift collapse of the PDPA government. Most significantly was the opening of negotiations by Uzbek strongman and Parchami, Abdul Rashid Dostum, with Ahmad Shah Massud to form a ‘Northern Alliance’. The final drive for rebellion came, as the Afghanistan Justice Project has detailed, when Najibullah attempted to replace General Mumin, the Tajik commander of the Hairatan garrison, with a Khalqi Pashtun: “Mumin revolted, with Dostum’s support. On March 19 the northern alliance of Massoud’s forces, Dostum’s, those of Hizb-i Wahdat and Parchami rebels took control of Mazar-i Sharif.” Kabul was to fall the following month, when, as the UN Mapping Report (briefly published by the UN in 2005 and then taken down, but not before being cached and re-published here) described it:

Fearing that the Northern Alliance would move on Kabul first, Khalqi Pashtuns and Hikmatyar, backed by Pakistan, arranged to infiltrate Hizb-i Islami fighters into Kabul. Massoud preempted them by taking control of the Afghan army garrison and its communications as various units dissolved or defected to different sides.

In 1992, large parts of the security forces did not put down their arms as they did in 2021, but joined the mujahidin factions or former PDPA militias, splitting largely on ethnic lines, ushering in a new and bitter round of conflict in most of the country. However, as in 2021, the switch in territorial control was sudden, massive and nationwide and came when the PDPA appeared to be losing. Moreover, it came as the UN, in 1992, and Khalilzad, in 2021, were still trying to patch up a peace deal.

Far more important to the staying power of a new regime than how it takes power, however, is how it then behaves. The crucial lessons from history for the new Taleban administration would seem to be the actions of the US-backed Karzai administrations.

Chart by Roger Helms for AAN.

2021 v 2001 v 1996: lessons from history for the Taleban

What happened following the defeat of the Taleban in 2001 is important for considering how secure the Taleban’s second Emirate might be. In 2001, the sense of relief and hope among Afghans was enormous, as the author, the BBC correspondent during those years, witnessed. That hope was centred not particularly on the defeat of the Taleban, but in the sense that Afghanistan’s long war might finally be over. The desire for peace was deep, fervent and pro-active. Afghans were long-suffering, before finally for some, the behaviour of the new administration and its American backers triggered revolt.

The new government was not of the people’s choosing. Into the vacuum created by the US’s bombing of the Taleban had come the old commanders and factions who had been defeated by the Taleban – or hung on in the resistance – during the first Emirate. They captured governorships, both provincial and district, ministries, army corps and police headquarters. About four-fifths of the first cabinet were military men or civilian members of tanzims (political-military factions). At least 20 of the first 30 provincial governors, Antonio Giustozzi assessed, were “militia commanders, warlords or strongmen,” while “smaller militia commanders also populated the ranks of the district governors.”[10] Those gaining positions of power in the post-2001 state then imported men, patronage networks and organisational structures that had developed over many years of war into the post-Taleban state, again directly influencing the political sphere. [11]

This grab for power, which was then sustained by US backing and international funding, was seen across Afghanistan and coloured the nature of the Republic for the next twenty years, as the author has reported. Securing funds through gaining office in the new state also allowed civilians like Hamed Karzai and his brothers, and Ashraf Ghani to rise to power. With little need to tax because of huge international civilian aid and military support, Afghanistan’s leaders and the post-2001 state were financially autonomous from Afghan citizens.

Despite what would prove to be systemic problems, the chance for a long-lasting peace in 2001 was great. The Taleban defeat had been incontrovertible. Mullah Omar had offered a surrender (it was refused) and commanders and fighters had gone home to live in peace or, in the case of the more major players, had slipped across the Pakistani border with the aim of getting security guarantees from the new authorities and coming back home to live. Yet, the US ‘hunted down’ Taleban remnants. That policy, to combat what was actually a fantasy of continuing armed resistance, eventually triggered actual rebellion.

The early years after 2001 saw the persecution of Taleban trying to live in peace, including the double-crossing of Taleban commanders trying to surrender, as well as looting, beatings, rape, killings and land grabs. [12] The violence was not limited to former Taleban. Victorious Afghan commanders fooled the CIA and US military by making false claims against their tribal and factional enemies and getting them detained. False accusations were also made for money. The result was that US forces carried out mass indiscriminate detention in those years. Forcing entry into people’s homes as they searched for Taleban and members of al-Qaeda, they disturbed women living segregated lives, stripped men in public and used ‘unclean’ sniffer dogs. Detentions by US-allied Afghan groups – who might officially be police, or from the governor’s office or the forerunners to the ANA – were often accompanied by the extortion of money and looting of property. Both Afghan and US forces routinely used torture, while the US embarked on the sorry and continuing saga of rendering Afghans and others to Guantanamo outside either the criminal law or the Geneva Conventions (for detail on the Afghan experience in Guantanamo, see this special report).

Being allied to the US military typically gave local Afghan forces effective impunity, amplifying their ability to commit crime and target rivals. Throughout the north, as Human Rights Watch documented, in the months after the fall of Kabul, victorious Hizb-e Wahdat, Jamiat-e Islami and Jombesh-e Milli forces, as well as armed Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Hazaras, targeted Pashtun communities with “looting, beatings, abductions, extortion… incidents of killing and sexual violence,” stripping them of their assets and impoverishing them and leading many to flee their homes.

The background to these particular abuses was a string of massacres of non-Pashtun civilians, which the Taleban had perpetrated as they sought to subdue the north between 1998 and 2001. Their strategy was to target civilians of the same ethnicity as factional fighters from the Northern Alliance when those factions had re-captured territory and then lost it once more to the Taleban. It was part collective punishment, part deterrent. (For details, see Human Rights Watch reports here and here and the Afghanistan Justice Project report and in our July report on the fall of the north in 2021). Human Rights Watch in its 2002 reporting stressed that “many ethnic Pashtuns living in northern Afghanistan did not participate in abuses against their neighbors,” but the “brutality of Taliban rule in northern Afghanistan has left many communities… with grievances that, in the absence of judicial mechanisms for accountability and redress, are being addressed in a vigilante fashion.”

In Kabul, as well, the new post-2001 authorities dominated by the Shura-ye Nizar faction of Jamiat conducted a mass detention of their Hezb-e Islami rivals in early 2002 as members met to discuss re-establishing their political party (reported on by the author at the time). Karzai also refused requests to set up a Taleban political party, which could have been a vehicle for peaceful political participation. (For more on this, see this AAN paper from 2010).

The other major type of abuse perpetrated by the new government on its citizenry more generally was related to corruption. The level of graft and bribery in the Karzai administration shocked and dismayed the public and undermined the government’s legitimacy, as the author discovered in a series of interviews in 2006 when she sought people’s memories of Taleban rule in Kabul. Virtually every interviewee turned the question round, using it to express his or her disgust with the Karzai government, as one old man in west Kabul said: “The officials suck your blood. Even governors take bribes just for doing something legal. The Taleban beat women and there were restrictions, but at least there was no bribery.” [13] That corruption in the Republic was at unprecedented levels was also reported by the US Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction in its lessons learned reporting on how corruption.

Afghans responded to corruption and in some places oppression with patience and active, peaceful attempts to get abusive officials changed by lobbying Kabul, with demands to be included in the new political set-up, and by refusing calls by those Taleban who wanted to start a ‘jihad’. When insurgency was eventually sparked and spread, the stories from different areas of the country of how rebellion came about were remarkably similar; after years of struggle, local people came to feel that the corruption and oppression of those in power was insupportable and the Taleban, themselves re-gaining members because of persecution, were able to piggy-back onto this unhappiness. [14]

AAN colleague, Martine van Bijlert reported that Afghans would commonly explain people joining the insurgency because they were narazi (dissatisfied – a reference to local leaders excluded from office and decision-making) or majbur (obliged or forced to rebel because of predation or abuses).[15] Research by Sarah Ladbury and the NGO, Cooperation for Peace and Unity (CPAU) in research for the UK’s Department for International Development looking at individual motivations for joining the insurgency found government corruption and partisanship at provincial and district level “was consistently cited as a major reason for supporting the Taliban and Hizb-e-Islami in all field study areas … the government’s record on corruption was deemed so extraordinarily unjust that ‘the people even prefer bad Taliban when the alternative is government.’”[16]

The Taleban insurgency was not inevitable. Hubris lay behind much of what went wrong after 2001, and a refusal to treat the defeated with dignity and respect. American policy was often based on a bizarre inability to see Afghans as anything other than black and white: Taleban = bad, anti-Taleban = good. The US fantasy of a continuing rebellion after 2001 that had to be put down was matched only by their determination to cast the Taleban as partners in a peace process in recent years.

Many commentators and international backers of the 2001 state have wished in hindsight that the Taleban had been invited to the Bonn conference where the new post-2001 state was established, believing this would have prevented the insurgency. See for example, this interview with British general Nick Carter in 2013 when he was deputy commander of ISAF. As Alex Strick von Linschoten, author of An Enemy We Created, said in response: “There would not have been too much negotiating to be done, even, in 2001 or 2002, because the Taliban’s senior leadership made their approaches in a conciliatory manner, acknowledging the new order in the country.” If the US and their victorious Afghan allies had just not persecuted the Taleban in defeat and treated them and other old enemies with respect, it probably would have been enough to have dampened down the desire to take up arms again, given how very war-weary the whole population was.

Now that the Taleban are back in power, still heady from a victory they believe is God-given, they are in danger of succumbing to the same trap as the Republic did, of alienating the population they are now ruling. Their government, all male, almost all Taleban and dominated by Pashtuns, is even more exclusive and even less representative of the country than the 2001/2002 cabinets were, while what appears to be the systematic killing of those they consider to be enemies and traitors, as well as land grabbing and forcible displacement, may drive rebellion yet.

Reinforcing this risk are the very different circumstances in which the Taleban came to power in 2021, compared to the 1990s. Then, except in parts of northern Afghanistan, the Taleban were often welcomed by people exhausted and made desperate by the brutal civil war. Bloody internecine fighting had wrought destruction, with civilians caught up in the violence, abused sometimes for money, sometimes solely because of their ethnicity or tribe. The Taleban’s founding story is centred on their defeat of abusive commanders to bring peace to the citizens of Kandahar in 1994. When they entered Kabul in 1996, as well, it followed four years of rocketing and bombing which had left a third of the city in ruins, tens of thousands dead and with ethnic-based factions cutting up the capital with their frontlines. In much of Afghanistan, where the Taleban disarmed commanders and co-opted civilian leaders locally, they were credited with bringing order, even if that order was harsh. Only in the north did they encounter real resistance.

How different has the Taleban’s rise to power in 2021 been. While civilians in some places have, as in the 1990s, seen the Taleban as a liberating force which has brought a blessed end to violence, elsewhere, the Taleban feel like a force of occupation. In cities like Kabul, they are associated not with bringing peace and order, but with killing large numbers of people in mass-casualty attacks and through IEDs and targeted killings. In much of Afghanistan’s countryside as well, the death toll from the insurgency over many years has been high, from IEDs and attacks on military or civilian government targets that took little notice of civilian life and property. In 2021, despite the drought, as the Taleban captured districts, they immediately took ushr (a religious tax on farmers) and billeted soldiers on villagers who often could not afford to feed them (see the Amnesty International report p 10).

The peace of 2021 has also not been welcomed as the peace of 2001 was. Then, the country emerged from isolation and destitution with a hope for better days; even the Taleban went home accepting their rule was over. In 2021, the relief felt by many that they no longer need fear catastrophic violence – from IEDs and airstrikes, suicide attacks and mortars – quickly gave way to the terror of what the collapsing economy would mean for them and their families. Isolation and destitution have once again engulfed the country and in the months ahead, hunger and winter itself will be the main enemy facing the Afghan people.

Lessons from history that may favour Taleban rule

Compared to previous governments, the Taleban can point to much that is in their favour. They control all the territory of Afghanistan. There are no safe havens from which a military or political opposition can base itself. Those who opposed the first Emirate, not only factional fighters and leaders but also intellectuals and professionals, could find refuge in what, in the end, came to be shrinking territory in the north. They could remain in the country, or at least stay close by, in Iran or Pakistan. This time, all of Afghanistan is under Taleban rule. The speed of the collapse meant there was no time even to organise an opposition. Moreover, the exodus of many of the country’s brightest, aided by international evacuations, has stripped the country of many Afghans who were likely to have joined or lead civilian or military resistance.

In 2001, the Taleban also faced a country entirely under Kabul’s rule. It was the first time in almost a quarter of a century, since the armed rebellions against the 1978 communist coup (also known as the Saur Revolution), that Afghanistan had been under one authority. Yet, in 2001, the Taleban had Pakistan at their backs. Pakistan proved to be a safe haven for leaders to organise from and for commanders to rest up from the war. Pakistan was fundamental to the Taleban’s ability to start an insurgency and steadily consolidate their gains.

Significantly, in 2001, even while Afghans, and many Taleban themselves, viewed the war as over and the Emirate finished, that view was never widespread in Pakistan. There, popular opinion held that the Taleban were heroes, and Afghans the victims of American imperialism, with even liberal Pakistanis from 2001 onwards believing Afghans were suffering under the yoke of foreigners.[17] The Taleban fight may well have kicked off because of wrongs committed inside Afghanistan, but those who fled found a safe haven across the border and a narrative of oppression and resistance already fully formed. Islamabad provided the Taleban leadership and its fighters with a safe harbour from which to organise, train, recuperate and get military advice and expertise. Pakistan was essential to the Taleban insurgency and their victory in 2021.

Today, Afghanistan’s neighbours may prove to be helpful in sustaining the new administration; no regional country yet looks to want to play the same role that Pakistan played in nurturing the Taleban in opposition. Some of the Republic’s senior officials have found sanctuary in Tajikistan, Iran or Turkey, but there is as yet no sign that they are being allowed, at least openly, to agitate and organise from those countries or that they are being supported to do so. Yet, history also provides warnings of how, if Afghanistan does begin to fall apart, neighbourly support to opposing factions can fuel conflict, as it did in the 1990s, even after the major international players had lost interest in the conflict.

Also in their favour, the Taleban can point to their relative unity, especially when compared to the array of factions that made up the mujahedin, who fell to fighting among themselves even before the defeat of the PDPA in 1992. Commentators who highlight the factions within the Taleban and the prospect of disunity and infighting must so far have been disappointed. There has been rivalry and even some fighting, particularly between the Haqqani faction and those who led the supposedly more moderate political efforts, and the powerhouses of the insurgency, the Taleban networks from the south and southwest, but there has been nothing remotely comparable to events in 1992 – or even in the first years after 2001. Then, it was only the threat of US airpower that kept Hezb-e Wahdat from marching on Kabul from the west after Shura-ye Nizar had captured it in November 2001, or that in those early years largely kept powerful rivals – Dostum and Atta Nur Muhammad, Dostum and Ismael Khan, Ismael Khan and Gul Agha Shirzoi – from fighting over turf.

Even so, the Taleban’s decision to prioritise internal coherence, including by rewarding cadres and the different networks within the movement with government posts has meant a very exclusive administration (AAN analysis of the appointments here and here). This carries its own risks, that mullahs are appointed where experienced professionals would do a better job, that most Afghans do not recognise the government as representing them at all, and that relations with potential donors are endangered when other countries, both regional and further afield, continue to demand “inclusive government.” (see detail here).

One downside for the Taleban today is their lack of friends and money. The comparison with the post-2001 state is telling. Officials in the Karzai and later Ghani governments may have seen the state largely in terms of opportunities for patronage and money-making rather than a means to serve the people, corruption may have been rife in a way that is not (yet) troubling the Taleban and the state may not have been particularly popular with its citizens, but officials could still rely on the largess of foreigners to keep them in power. Civilian aid and military support flowed into Afghanistan, and foreign governments sent their soldiers to kill and die defending the Republic.

The Taleban, in utter contrast, have seen the vast flows of foreign money that had been coming into the country – over 40 per cent of GDP until 15 August – stop overnight (see AAN reports here and here). The banking sector is paralysed for want of hard currency, and the country’s foreign reserves have been frozen and put out of reach of the new administration. UN and US sanctions that had applied to the Taleban or its leaders now apply to the Taleban government, and therefore, inevitably also to Afghanistan. The US initiated limited humanitarian waivers from 24 September (texts here), broadening those out from 22 December (see texts here and Reuters report here); also, on 22 December, the UN enacted exemptions for humanitarian activities and “other activities that support basic human needs” (press release here). Large amounts of humanitarian aid have been promised, but as AAN reported in November (and it still holds true), these are drops in the ocean compared to the vast funds that had flowed into the country. No country has yet recognised the new government, not even the Taleban’s main backer, Pakistan.

The Taleban lack rich and powerful international backers in the mould of the western donors who, in the 2000s, were able and willing to put steady and sufficient revenues into the Afghan treasury. The economic catastrophe that was inextricably and inevitably linked to the Taleban decision to seek power through military victory could yet undermine the new government. Hungry people rarely rebel, but competition over scarce resources could prove a centrifugal force that undermines Taleban unity and the leadership’s control of its own commanders. Whether revenues from border posts, drugs and mines continue to come reliably to the central coffers will be important to watch.

Conclusion

Lessons from history are telling, but it is also important to stress that Afghanistan has itself changed in the last twenty years. The Taleban will already have found that Afghanistan is far trickier to rule and to win legitimacy from the people than when they were last in power.

Many women in particular have had the opportunity to become citizens with a public ‘face’, with paid jobs and for some, political or activist roles. Not all women were able to enjoy these opportunities, but as we found when speaking to women in rural areas about war and peace for a special report published in July 2021, there was a strong and widespread desire for greater freedom of movement, education for their children (and sometimes themselves) and a greater role in their families and wider social circles. Restrictions on women’s lives may be easy to push through now, but may also drive resentment, including, for example, of technically able Afghans that the Emirate needs and who may decide to leave if, for example, they cannot get their daughters educated.

Afghanistan’s population is more urban, more educated and more connected, through social media and a working phone service (there were barely even landlines in 2001), both to each other and to the world. Unhappiness with Taleban rule – of media restrictions, blocking women from taking roles in public life, banning them from working and older girls going to school or college, of jobs given to Taleban and the threat of summary execution or forced disappearance – could yet translate into concerted civic resistance. There have been more protests in the last few months than in all the years of the first Emirate, especially by women. Despite the corruption and nepotism of the Republic, the opportunities – or at least hopes – it offered, for education, better healthcare and routes out of poverty, have changed Afghans’ expectations of what a state should deliver and what they themselves can aspire to in life.

In the end, however intelligently and bravely the Taleban fought, they were unprepared to govern. In the past, in areas they controlled, as AAN research showed, they could rely on the government, NGOs and ultimately foreign donors to keep services like clinics and schools running, while Taleban health and education commissions could tinker around the edges – changing the school curriculum or staff hiring. That is a very different role from being responsible for public services for a whole nation. The Taleban were very good at running an insurgency. Now they face the much more difficult and far more complex task of running a country.

Edited by Roxanna Shapour and Rachel Reid

References

| ↑1 | There was always a great deal of debate about what ‘control’ meant: governing, the ability to travel safely, or denying the other side movement? When we started mapping the fall of Afghanistan’s districts in 2021, we opted for the metric of who controlled the district centre only, for simplicity and relative ease of determining the data. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In October 2020, we wrote about how violence had not reduced after the February 2020 US-Taleban agreement, but that there had been:

… a sharp rise in the incidence of smaller attacks and targeted assassinations. Government officials and security personnel, as well as human rights advocates and religious figures have been killed and injured in what appears to be a carefully calibrated campaign of violence using magnetic IEDs, suicide bombers and small teams of gunmen in Kabul and provincial and district centres… Small to medium-sized coordinated attacks against ANSF outposts and checkpoints have continued at a steady pace, while the use of Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) targeting ANSF vehicles and convoys, particularly on highways, appears to have risen in some areas. Suicide bombings rarely seen in the cities, on the basis of what appeared to be an understanding between the US and Taleban even before the February 2020 agreement was signed, did start to be used against military targets, while the targeted killing campaign appeared aimed at spreading fear and draining confidence in the strength of the government to protect people in the same way as mass casualty urban attacks would do, but more quietly. By autumn 2020, the Taleban launched major offensives against Lashkargah, capital of Helmand province and Kandahar city – which did attract US airstrikes. |

| ↑3 | The patterns of conflict in the years 2014-2018 are reminiscent of 2021. After NATO’s ISAF mission ended and Obama gave only very limited permission for US forces, the only international forces still fighting after that, to use airstrikes, the Taleban used the opportunity to conduct mass attacks and captured large amounts of territory. The US came back into the war and supported the ANSF in pushing back Taleban control. There were high levels of civilian casualties throughout. |

| ↑4 | Reports that CIA-proxy Afghan forces (the Khost Protection Force, Shahin Force and 00 NDS forces) were no longer receiving orders to conduct night raids after the February 2020 Agreement also appeared borne out by their disappearance from UNAMA civilian casualty reporting. At the beginning of the fourth quarter of 2020, reports of civilian casualties from these groups were again reported by UNAMA. This was also when the US began to use more airstrikes against the Taleban. See this AAN analysis for more detail. |

| ↑5 | In AAN analysis of the conflict and civilian casualties in 2020, we wrote:

There has been much discussion of who is responsible for these killings, given how few are claimed. Of those targeted killings included in its 2020 Protection of Civilians report, UNAMA attributed nearly two-thirds to the Taleban – 761 civilian casualties (459 killed and 302 injured) – a 22 per cent increase from 2019. In general, the Taleban have been far more reluctant to claim attacks than in previous years. We tracked this in a report in August, “War in Afghanistan in 2020: Just as much violence, but no one wants to talk about it”, but UNAMA has now quantified this trend further. Civilian casualties from attacks claimed by the Taleban fell by 85 per cent in 2020 compared to 2019. At the same time, the number of civilian casualties which UNAMA attributed to the Taleban from incidents which were unclaimed rose by 16 per cent; in these incidents, 3,700 civilians were killed (1,426) and injured (2,274). Overall, there was a 158 per cent increase in casualties caused in insurgent attacks the authors of which UNAMA could not determine – 826 civilians killed (202) or injured (624). |

| ↑6 | Scrolling down the OCHA page, you can see displacement by month, and by region. |

| ↑7 | See also head of UNAMA Debra Lyons’ briefing to the UN Security Council on 17 November 2021 and her reference to “house searches and extra-judicial killings of former government security personnel and officials.” |

| ↑8 | For an earlier example of this, mujahedin leader Abdul Rab Rasul Sayyaf was detained but spared President Hafizullah Amin’s purges because he was related to Amin on his mother’s side (see footnote 1 in this report on the disappeared from the first 20 months of communist rule. |

| ↑9 | As we wrote after the fall of:

Even as districts and eventually provinces fell, Washington clung to the mirage of peace talks. On 25 June, when more than a third of Afghanistan’s districts – 149 out of 421 – were in Taleban hands, US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said they were “looking very hard at whether the Taliban is, at all, serious about a peaceful resolution of the conflict.” Scarcely believable were comments by Khalilzad on 3 August, when more than half – 248 – of Afghanistan’s districts were in Taleban hands, and after weeks of the government defending or losing territory, and the Taleban attacking and taking territory: he warned “both sides of a “protracted war” if they focused on a “military solution.” He urged the Taleban and government instead to “focus on finding a formula for the ‘formation of a new government that is acceptable to both parties’” (Radio Liberty report here). |

| ↑10 | See Antonio Giustozzi, “Koran, Kalashnikov and Laptop: The Neo-Taliban Insurgency in Afghanistan”, London, Hurst, 2007, 16. |

| ↑11 | One example were appointments by the new defence minister, General Qasim Fahim, leader of the Shura-ye Nazar network within Jamiat-e Islami which had captured Kabul (thereby gaining the ministries of defence, interior and foreign affairs and the NDS). In February 2002, he appointed 38 generals in February 2002 as the new general staff; 37 were his co-ethnic Tajiks and 35 were with Shura-ye Nazar. Of the 100 generals he appointed in total, Giustozzi wrote, 90 belonged to Shura-ye Nazar. |

| ↑12 | Deedee Derksen, The Politics of Disarmament and Rearmament in Afghanistan, USIP, 2015, https://www.usip.org/publications/2015/05/politics-disarmament-and-rearmament-afghanistan, 15 |

| ↑13 | Interviews for Channel 4 News, January 2006, no URL; transcripts with author. |

| ↑14 | A typical account came from a graduate in his twenties (and confirmed by other interviewees, including local NGO workers) of how Sayedabad district in Wardak province came to accept the Taleban, despite years of its people telling them to take their ‘jihad’ elsewhere:

After 2001, in our province, people were very optimistic that peace and stability would come and a proper government that would care about the people. In the first one or two years, they were waiting, but it didn’t happen. Instead, there is a corrupt and inefficient government which is indifferent to the people and it gained momentum. Optimism was slowly replaced by disappointment – specifically in our district. Imagine: a district police chief was assigned by Kabul – and the police under him were robbers. They plundered and looted and raided people’s houses. So what happens next? When people saw those things that were done by the police chief, they became angry and, to take revenge, they stood against him and his group. The Taleban used this opportunity, grabbed it, they saw a community angered by the government and they attacked the district headquarters. Our district is all Taleban now. The people support them. The sense of disillusionment he expressed in the foreign forces was also common: I want to add that disappointment started with the government and it was exacerbated by the government and the Americans, and now there are even stronger reasons to be unhappy about the current situation. For example, in our area, Americans have made their bases in people’s houses. They’ve blocked the road for 5000 houses and blocked the irrigation system for a large agricultural area and water for the mosque. And they’ve started cutting down trees on both sides of the road – because they fear ambushes. People used to think foreign forces had come here to ease life and help the people – but their presence is a problem. They create support for the Taliban. Similar accounts from other parts of the country include: Frank Ledwidge, “Justice and Counter Insurgency in Afghanistan: A Missing Link”, RUSI Journal 154(1)(February 2009), Graeme Smith, “What Kandahar’s Taliban Say”, in A. Giustozzi (ed.), Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field (New York/Chichester: Columbia University Press/Hurst, 2009), p. 160; Antonio Giustozzi and Christophe Reuter, The Northern Front: The Afghan Insurgency Spreading beyond the Pashtuns, Kate Clark “2001 Ten Years on (3): The fall of Loya Paktia and why the US preferred warlords; Anand Gopal, The Battle for Afghanistan: Militancy and Conflict in Kandahar, New American Foundation, November 2010; Anand Gopal, “No Good Men Among the Living: American, the Taliban and the War through Afghan Eyes”, New York, Metropolitan Books Henry Holt and Company, 2014; and Stephen Carter and Kate Clark, “No Shortcut to Stability Justice, Politics and Insurgency in Afghanistan”, Chatham House December, 2010. |

| ↑15 | Martine van Bijlert, “Unruly Commanders and Violent Power Struggles”, in Antonio Giustozzi (ed.), Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field (New York/Chichester: Columbia University Press/Hurst, 2009), p 160. |

| ↑16 | Sarah Ladbury and Cooperation for Peace and Unity (Afghanistan) (CPAU), “Testing Hypotheses on Radicalisation in Afghanistan: Why Do Men Join the Taliban and Hizb-i Islami?” (2009) No URL to be found. |

| ↑17 | In February 2003, reporting for the BBC, I drove from Islamabad to Peshawar and on up to North Waziristan and the Afghan border. I found, as I wrote about a decade later for AAN https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/war-and-peace/talking-to-the-taliban-a-british-perspective/”>here:

Ordinary Pakistanis and government officials alike believed that, as I reported at the time, ‘the Taliban were heroes and victims of American imperialism’. In Peshawar, a religious right wing alliance, the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA), had just won provincial elections in protest at the US attack on Afghanistan. In Karachi, 70,000 people had just rallied, holding up posters of Osama Bin Laden as hero and George Bush portrayed as Hitler. In the capital of North Waziristan, Miram Shah, the government agent, who is the representative of the Islamabad government in a tribal area, lectured me on Islam, counting off the five pillars of the religion; he included jihad, instead of zakat (alms) and was not pleased when I pointed out his error. Even liberal Pakistanis believed Afghans were now suffering under the yoke of foreigners. For someone who had spent time across the border, the narrative was completely alien – and a shock to hear. |

REVISIONS:

This article was last updated on 30 Dec 2021