A mother of a little girl who was betrothed to a 23-year-old man to whose family her husband was indebted, sitting inside a tent at the Shamal Darya Internally Displaced People (IDP) camp in Qala-i-Naw, Badghis Province, October 2021. (Photo by Hoshang Hashimi / AFP)

A mother of a little girl who was betrothed to a 23-year-old man to whose family her husband was indebted, sitting inside a tent at the Shamal Darya Internally Displaced People (IDP) camp in Qala-i-Naw, Badghis Province, October 2021. (Photo by Hoshang Hashimi / AFP)

Although there are no solid statistics to corroborate whether underage marriages are on the rise in Afghanistan,[1] anecdotal evidence, media reporting and the context of widespread and deepening poverty strongly suggests they are. The first report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Afghanistan, published on 10 September 2022, which quoted some survey data, expressed concerns about “the reported surge of child marriage.”[2] Anecdotally, it also seems that more Afghans than in the past knew or had heard about families marrying off a young daughter. For this reason, the author decided to talk to such families to better understand how they had come to this decision and whether there was indeed a trend.

It turned out to be difficult to find people willing to be interviewed on the topic. While the author managed to identify and contact 11 fathers who had married off an underage daughter, and they all admitted to having done so, seven were unwilling to speak about it. Only four of the fathers agreed to an interview. Those who did speak – and most of the ones who did not – admitted to feeling guilty, depressed and ashamed over what they had done.

The four fathers who spoke to AAN were from Helmand, Kunduz, Laghman and Kabul city; the girls who were married (or promised in marriage) varied in age from 5 to 13. The two oldest girls, both 13 years old, had a wedding ceremony and moved into the houses of their husbands, respectively a 45-year-old mullah who already had a wife and the 20-year-old son of a business partner the father owed money to. Both fathers said they thought their daughters were happy in their new lives, although it would probably have been difficult for them to admit otherwise, and the girls themselves may have felt it impossible to ‘complain’ to their fathers if they were unhappy.

The arrangements for the two younger girls, a 11-year-old girl contracted to the 20-year-old son of a landowner and a five-year-old girl contracted to the seven-year-old son of a neighbour, were different. These girls were only promised in marriage. However, in Afghanistan, this ceremony, often translated as ‘engagement’ – kozdhda in Pashto and shirin khori in Persian – is considered binding and backing out of the subsequent marriage itself will bring enmity between the families. The families of these girls reached an agreement that the marriage would take place only after their daughters had reached puberty or the parents thought that their daughter was ready to be married. Till then, they would stay at their parents’ homes.

None of the girls were consulted about their marriage. In some cases, they were not even informed beforehand. The fathers generally feared they would cry a lot. All four of the fathers did say they had consulted their wives, and most also more widely within the family. One of the wives decided to meet the prospective groom to see if he and his family were suitable and herself agreed to the marriage; two opposed the marriage, but were eventually ‘persuaded’ or ‘gave in’, and the views of the fourth mother were not reported.

One striking feature of the interviews is that none of the fathers who spoke would normally have considered marrying off a young daughter. In all four cases, they felt the pressure to repay their debts was inescapable and there was no other way to find the money. All of them, including the ones who did manage to clear their loans, quickly found themselves again without money or income – no better off than before, but now having married off a young daughter.

The interviews were conducted in July/August 2022, by phone and in person, and have been lightly edited for clarity and flow.

1. Father of six children, 62 years old, Pashtun originally from Ghazni, living in Kabul city: “In our community, people call a bride price the ‘meat of a daughter.’ I’ve been eating my daughter’s meat and soon I will finish it.”

I married my 13-year-old daughter to a 45-year-old mullah from our village in Muqur district in Ghazni province. We’re relatives, but not very close. He’s a wealthy man and already has another wife who’s older than him; he has three children from her. His brothers came to my home and said they wanted me to marry my daughter to their brother. I asked them to give me some time so I could talk their proposal over with my family. I consulted my close relatives, and my wife and son as well. After two weeks, we reached the decision that I should do it and give my daughter to the mullah.

I threw a party and invited the other family. The mullah’s six brothers and some of his other relatives came. I also invited some of my own close relatives, men and some women. At the [engagement] party, I gave my daughter to the mullah. We agreed on a bride price – 1,000,000 Pakistani rupees (about USD 5000). We also agreed that the jahez would be bought by the groom’s family.[3] So they were the ones who supplied all the necessary things for my daughter’s household, not me.

Marrying my girl off at this early age was the most difficult decision I ever made in my life, and to a 45-year-old man who already had a wife. But speaking frankly, I had no other options left. I had been a police officer, first in Dr Najib’s era and then in the Karzai and Ghani eras. I was retired when Ashraf Ghani was president and had been getting at least some of my pension every year, but for the last two years, I didn’t receive any. My son was a police officer in the interior ministry in Kabul. He lost his job too.

I was in debt for eight months of rent to the landlord – a total of about 50,000 afghanis (around USD 550) – and I’d also spent money on the wedding of my older daughter. She got married three years ago to a teacher, when she was 21. I only took money from the groom’s family to buy her jahez [so, no bride price] and I spent about 100,000 afghanis (around USD 1150) on the different ceremonies. We have to follow some of our traditions. If you don’t, people will laugh at you. I also owed about 70,000 afghanis (around USD 800) in loans from friends and relatives. I paid off these debts using the bride price I received for my younger daughter.

The wedding was about four months ago. The groom’s family paid the bride price in three steps. They gave me 400,000 rupees (around USD 2000) when the couple was engaged. Two months later, they gave me 300,000 (around USD 1500). I received the remaining 300,000 a few days before the wedding of my daughter.

Recently she came to my home. It was during Eid, she spent four days with us. I think she’s happy because she didn’t complain about her life. In the beginning, after she was engaged, she cried a lot. I was also very frustrated and anxious and I couldn’t sleep for several nights. For weeks, I felt exhausted and my heart didn’t want to speak to anyone. But there was nothing left that we could do, other than marry off my daughter so we could feed the rest of the family.

In the past, people would sometimes marry their daughters while they were still children, but for the last fifteen years or so, I hadn’t heard of any girl being married in childhood – at least not until recently. Now, the practice has increased again and I’ve been hearing about it again.

I never imagined I would marry one of my daughters while she was still a child. And I’ve been spending my daughter’s bride price. In our community, people call this money the “meat of a daughter” because taking a bride price is completely illegal in Islam. But I’ve been eating my daughter’s meat and soon I will finish it.

2. Father of five children, 40 years old, Tajik from Dasht-e Archi district, Kunduz province: “I really made a blunder. I married my underage daughter because of poverty and now I still remain in poverty.”

There are eight people in my family. I have two wives and five children. The daughter who I gave in marriage is my eldest child; she is 11 years old. She doesn’t go to school. My whole family, including my wife and brothers, are uneducated.

I used to have a job in the government where I received 13,000 afghanis as my monthly salary (nowadays worth around 150 USD). I was able to feed my family on this. When the government collapsed, I lost my job. I didn’t have any alternative, except to marry my daughter to someone. I married her to a 20-year-old man. He is the son of one of our villagers, but we’re not relatives. In our family it isn’t a custom to marry small girls, we always waited until puberty. I’m the only one within my family who’s marrying a daughter who’s still a child.

I did this, even though her mother didn’t agree. But my other wife, who’s the girl’s step-mother, helped me make the mother of the girl agree. Finally, after about a month, she consented. We didn’t tell our daughter at first that we were getting her married. When she found out about it, she cried a lot.

We had a small celebration, in which the father-in-law of my daughter gave me 30,000 afghanis (around USD 350). At the engagement party, we repeated our agreement that my daughter wouldn’t be married until she reached puberty. We’d also decided that the father-in-law of my daughter would pay me the rest of the bride price within six months. The full bride price was 250,000 afghanis (around USD 3000).

But more than six months have passed and he hasn’t given me the remaining money yet.

He’s not a bad man. I thought he had enough money to give me, because he has more land than many of us in the village, but unfortunately it turns out he didn’t have the cash. He’d also made a plan to marry his daughter and I knew he would probably receive more money than me because his daughter was an adult. The bride price for a woman in our area is usually around 400,000 to 500,000 afghanis.

He did get his daughter married – to someone who is not from our village and not even from our tribe. I went to the engagement party. I think the bride price they agreed upon was 600,000 afghanis. But the father-in-law of my girl was only given 50,000 afghanis by his in-laws on that first day. Since then, he has received nothing.

I’m now helplessly waiting for the money he owes me. I really made a blunder. I married my underage daughter because of poverty, but now I still remain in poverty. I believe this happened to me because of the sin I perpetrated by marrying off my small daughter.

3. Father, 50 years old, Tajik from Nangrahar, living in Laghman province: “After I paid off the loan, very little money was left. I’ve now finished all of it. But I’m happy that at least one of my children can find a meal three times a day.”

I married my 13-year-old daughter to a young man of 20. I was indebted to shopkeepers for around 150,000 Pakistani rupees (around USD 750). Some were continuously demanding that I repay the loans. They were even going to my relatives and telling them that I should pay back the money I owed. Finally, I decided to sell my land. After that, I took the money and started a business with another person. We were buying cows and after a few days selling them in the market, making profit on the difference in price. We both invested in the business, but my partner, who was also from Nangrahar, invested more than me.

After two months, we sold six cows with a profit of about 60,000 Pakistani rupees (around USD 300). The buyer took the cows and told us he’d send the money via hawala. We trusted him because we’d sold him cows twice before. But he went away and didn’t send us our money. He just disappeared. We still don’t know where he is. We searched a lot for that man, but we couldn’t find him.

My business partner gave me about 200,000 Pakistani rupees as a loan (around USD 1000), but after we didn’t find the person who robbed us of our money, my partner kept calling me to give him back his money. One day, he came to our home. I offered him tea and my daughter brought it in. When he saw my girl, he suggested I should marry her to his son, instead of paying him back his money.

I was very angry but said nothing. I just laughed, but I felt furious. When he left, I told my wife what the man had said. My wife wept but said nothing. She was also anxious about our economic circumstances. My business partner kept coming and asking me for his money. Finally, my wife said she would go to his home to meet his son and his wife. She went and when she came back, she said she’d agreed to the marriage. She said the boy was a good boy and his mother was a good woman, but I could see that she was unhappy about it.

Finally, we decided to marry our daughter to the son of my partner. We had small celebrations on both the engagement and the wedding day. My partner invited his close relatives and so did I. In our community, we don’t take too high a bride price. It’s not our custom. I only took 200,000 afghanis (around USD 2500).

After I paid off the loan, very little money was left. I’ve now finished all of it. I go to the bazaar looking for work. Sometimes, I can find some, but most of the time I come back empty-handed. When my wife and children see me come home without finding any daily labour work, they become unhappy.

I think my daughter is happy with her new family. And I’m happy that at least one of my children can find a meal three times a day. At least one of my children is fed.

We didn’t consult our daughter because we knew if we talked it over with her, she would cry. And she did weep a lot on the day of her engagement, as did her mother. But we could do nothing else. I was in such a bad economic situation that I had to marry my girl at such a young age.

4. Father of three children, 36 years old, Pashtun from Helmand province: “I used to condemn people who gave their children in marriage. And I really regret what I did, but there was no other alternative.”

I married my five-year-old daughter to a seven-year-old boy in our village. I talked it over with my wife beforehand. She didn’t agree, but I persisted and finally she gave in because she knew there was no alternative.

I owed 100,000 Pakistani rupees (around USD 500) after I bought a cow on credit. I thought I would graze the cow and sell the milk, and use the money to support my family and repay the loan. But the cow died. So, I tried to find a job in Lashkargah and elsewhere in Helmand. but I couldn’t find any work. For a while, I worked with a man in his shop, but then I lost that job too.

Three months after I lost my job, the due date to pay back my loan arrived. The man I owed money to kept coming to my house twice a week, asking for his money. After a month, I decided to shift my family to another district to hide myself from the man, because there was no way for me to find work and make money to repay the debt on the cow. But two months later, the businessman found me. He insisted a lot that I pay him back his money.

When my neighbour found out I was in debt, he suggested that I marry my daughter to his son. We eventually agreed he would give me 300,000 Pakistani rupees (about USD 1,500).[4] He gave me 100,000 rupees in the week after we agreed to the match and said he’d pay the remaining money during the wedding. We agreed that the wedding would take place after my daughter’s 15th birthday, so in about ten years’ time.

After I received the money, I gave it to the owner of the cow. Now I don’t have any money left and I don’t know how to find work. I really regret what I did, but there was no other alternative.

I always used to condemn people who gave their children in marriage. I even tried not to go to their engagement parties. Now I’m full of remorse. I didn’t consult my close relatives at the time, but I hear that my fellow villagers are criticising me a lot, though they don’t say anything to my face. The people castigating me are my close relatives, who I didn’t consult when I was making this decision.

The four child marriages in context

Child marriage, especially of girls, is not uncommon in Afghanistan. Young girls are sometimes married to close relatives to strengthen kinship ties. For example, two brothers living together in an extended family may want to reinforce their bonds and decide not to delay the engagement until a girl has reached puberty. In that scenario, a brother contracts his young daughter to a nephew, but the two would usually not actually get married until she was considered old enough.

There are also darker reasons for giving a young girl in marriage, for example, to end a blood feud. In a so-called bad marriage, the family of the person accused of murder or manslaughter gives a bride to a male member of the victim’s family. Such marriages, always relatively rare, have become rarer in recent years. For example, in the author’s community there have been only three cases of bad marriages in recent decades, all about 35 years ago; two were to settle of cases of elopement and one followed a murder. However, where they do take place, a young bride is often preferred by bride’s family, as she is less likely to object or be able to block the marriage. Young girls also fetch lower bride prices, so her family loses less than if they were to marry an older daughter.[5]

As our four interviews illustrate, a more common reason driving early marriage is economic distress, and the practice, usual in Afghanistan and many other countries, of the groom’s family paying money to the bride’s family in the form of a bride price (walwar in Pashto and toyana and sherbaha in Dari). In general, older girls (but not too old) fetch a higher bride price. However, if a family has no older unmarried daughters and they are in desperate need of money, they might feel forced to consider marrying off a younger girl, especially in times of extreme economic hardship.[6] In Islamic law, the groom should also pay a financial pledge, mahr, to his wife. In Afghanistan, as elsewhere, the mahr payment rarely reaches the bride. She can exempt the groom from paying it, or ‘voluntarily’ give it to her father.

The author has witnessed marriage agreements in his community between close relatives who wanted to strengthen the ties between their families by promising their children to each other, but these engagements rarely involved the payment of mahr or a bride price, because of the close ties between those involved. If they did, the payments were minimal. He has never witnessed the marriage of an underage girl that involved significant payments of money if her family had a comparatively good economic life.

Many Afghans consider the practice of child marriage harmful, saying it ends a girl’s childhood far too early and raises the risk of maternal mortality, as girls who get pregnant during puberty are more likely to die in childbirth. It also takes away the opportunity for girls to have a say in whether, when and to whom they will be married.

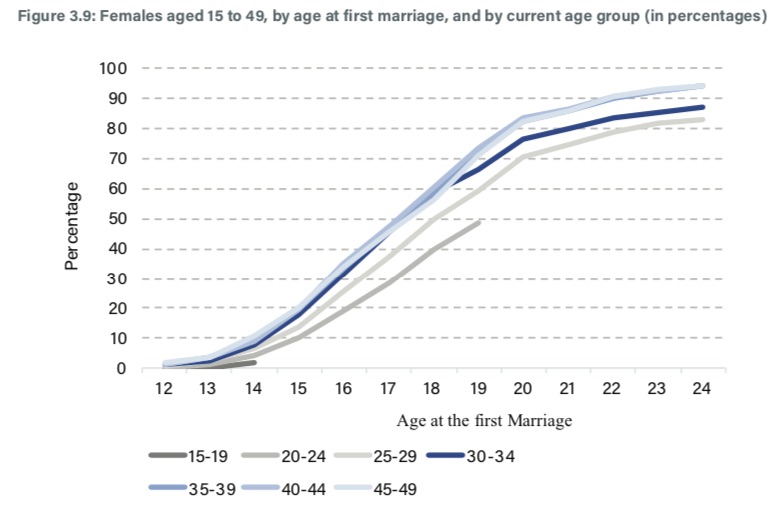

The Afghan Civil Law, ratified in 2009 by then president Hamid Karzai, fixed the marriage age at 18 for boys and 16 for girls, although girls who are 15 were allowed to marry if their guardian or the court agreed. Underage marriages, below the age of 15, were banned although the laws forbidding it were never actively enforced.[7] Regardless of the law, the age of first marriage has been slowly rising, at least it was up till 2016-17 when the last major nationwide survey of living conditions was carried out. At that time, nationally, 4.2 per cent of all women had been married before the age of 15 and 28 per cent before the age of 18.[8] The average age of first marriage at that time was 21.6 years for women and 24.4 years for men.

The survey, conducted by the Central Statistics Office, illustrated the rising age that Afghan women marry with a graph, reproduced below. A higher proportion of women now aged 35 and over in 2016-17 had been married by age 18, whereas for the younger age groups the percentage married at that age is lower: 58 per cent of those aged 30-35, 50 per cent of those aged 25-29 and 40 per cent of those between 20-24. In other words, the younger generations were, on average, getting married later. The graph also shows that the proportion of much younger girls, 15 and under, who were married had progressively fallen.

What do we know about the current situation?

The current leadership of the Islamic Emirate has not said anything about child marriage. The Taleban supreme leader Sheikh Hibatullah Akhundzada did issue a “decree regarding women’s rights” on 3 December 2021 which said, among other things, that forcing a girl or a widow to marry was illegal. However, he did not put a lower limit on the age at which girls could marry (see this Pajhwok report).[9] According to a Taleban judge, who gave his view to the author but did not want to be named, a girl must in principle have reached puberty to be married. However, if her guardian (wali), her father or grandfather, acts with her well-being in mind and there is “a good match” which could be lost while she grows up, exceptionally, he said, a prepubescent girl could be promised in marriage (kozdhda or shirin khori). The judge said that getting money in exchange for a girl of any age was illegal – haram – under Islamic law: any mahr paid had to go to the bride herself, while bride prices were illegal.

According to a recent report by Save the Children on children’s lives under Taleban rule, more than one in twenty (5.5%) of the 122 girls aged 9-17 whom they interviewed in May and June 2022 had, that year, “been asked to marry… to support their family.” The cases were more common for girls in female-headed households, which the charity said, “are experiencing the greatest financial pressures and gaps in meeting basic needs.”[10] The children in the study said that early marriages were happening:

…because families do not have enough money and are poor. Children recognise that this way of coping mainly affects girls, including very young ones. A few girls mentioned that if a girl in the family gets married, there is more money to take care of, and feed, her siblings. In addition, because older girls are no longer allowed to go to school, some parents believe that getting married instead will give them a chance at a better life.

Since the interviews for our report were only with fathers, they provide only limited glimpses into the feelings of the girls concerned, as well as their mothers. The Save the Children study did get a child’s-eye view of early marriage, although it seemed mainly from their peers, rather than the brides themselves. Girls aged 9 to 14 told the researchers how other girls in their community when they were married had been forced by their parents to give up school and/or move away to other areas. The girls worried that the same thing would happen to them and that “because of child marriage, they will never be able to go to school again, and that they will not have a future.” They said the possibility of having to marry an older man when they were still young was depressing, while they felt “frustrated and powerless” that their parents would not listen to them when it came to marriage.

None of the daughters of the four fathers interviewed had been ‘listened to’ when it came to their marriages. Girls who are engaged at this young age are never listened to. If they were, it is likely they would just cry.

Even so, of the eleven fathers contacted, most expressed shame about what they had done. They did not consider that marrying off their young daughters had been normal or good, but said that that in a situation when they were struggling to provide even food, they had been obliged to sacrifice one of their children to save the others.

The tragedy, of course, is that for most families the short-term injection of cash the marriage provided, while briefly solving the pressure and shame of owing large sums of money, did not solve the underlying problem. Most of these families were left still with no steady means of income and will be incurring more debt again soon.

Edited by Martine van Bijlert

The article was published in the Afghanistan Analysts Network.

References

| ↑1 | The UN Population Fund (UNFPA) told AAN it was not currently measuring child marriage. It had earlier, under the previous regime, been giving technical and financial support for the National Action Plan to End Early and Child Marriage in Afghanistan (2017–2021), developed by the then Deputy Minister for Youth Affairs and the Ministry of Women’s Affairs. A UNFPA official in Kabul told the author that the plan was, however, never implemented. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Afghanistan cited a draft document, The UN Rapid Gender Analysis Afghanistan – Secondary Data Review (Draft 3), dated October 2021 (excerpts seen by AAN). It quoted surveys that had found “the overall rate of child marriage has increased in the face of the current economic crisis and humanitarian need, with 6% of households reporting the marriage of daughters earlier than expected.” The prevalence of child marriage as a strategy to cope with economic distress was, the report said, most common in Helmand Province, followed by Kandahar and Faryab. The Special Rapporteur’s report can be found by searching for A/HRC/51/6 on this page, see also AAN analysis here. More survey data can be found in the recent Save the Children report, Breaking Point: Children’s Lives One Year Under Taliban Rule, quoted elsewhere in this report. |

| ↑3 | The jahez are the things needed to run a household, which might include dishes and cooking utensils, bedding and furniture and for richer Afghans, washing machines, televisions and cars. The jahez is traditionally given to the bride by her father. The interviewee added that the bride price is customarily agreed on in Pakistani rupees by those living in southern and southeastern provinces or among people who are originally from these regions. |

| ↑4 | The interviewee also said: “Before the takeover of the Taleban, the bride price for a woman used to be 1,200,000 to 4,000,000 rupees (USD 6000 to 20,000), but now it’s less, around 800,000 to 1,200,000 rupees (USD 4,000-6,000) for a woman.” The bride price for young girls has always been lower. |

| ↑5 | For more background on how bad marriages and how bride prices are fundamental to assessing ‘blood money’, another means of assuaging a blood feud, see the 2011 AAN special report Pashtunwali – tribal life and behaviour among the Pashtuns by Lutz Rzehak. |

| ↑6 | For more detail about bride prices in Afghanistan see AAN’s 2015 report, “The Bride Price: The Afghan tradition of paying for wives”. |

| ↑7 | The Shia Personal Status Law provided no minimum age, but said that underage girls could be married only if their guardian proved theircompetency and puberty to a court and the marriage would be in the girl’s interest. The extraordinary gazette of the Law on the Elimination of Violence against Women (EVAW) fixed a punishment of not less than two years imprisonment for people marrying or giving in marriage underage daughters. But, as said before, this was not actively enforced. |

| ↑8 | In urban areas, the percentages of women married before the age of respectively 15 and 18 were lower, 2.1 per cent and 18.4 per cent respectively, and in rural areas, higher, 5 per cent and 31.9 per cent, respectively. |

| ↑9 | Bad marriages were not mentioned specifically by Hibatullah. However, they were banned by the first Taleban supreme leader, Mullah Muhammad Omar. It was reported at the time that he was prompted by a moving storyline in the popular BBC radio soap opera, New Home, New Life about the plight of a girl who had been given in such a marriage. See this media report and this AAN obituary of one of the show’s actors. |

| ↑10 | Breaking Point: Children’s Lives One Year Under Taliban Rule, August 2022, Save the Children. The charity said that of all the strategies adopted by households to cope with economic pressure, child marriage was not the only one affecting children. The main strategies were: children being sent out to do paid work, children having to migrate for work (6%), children leaving the household to stay elsewhere (4%), begging (2.5%) and child, early, and forced marriage (2%). |

REVISIONS:

This article was last updated on 19 Oct 2022