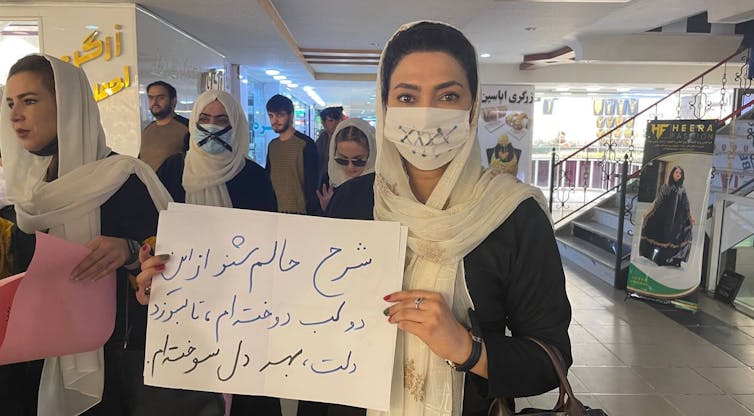

Bilal Guler/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Wazhmah Osman, Temple University and Helena Zeweri, University of Virginia

Ever since the Taliban recaptured Afghanistan, the question in much of the Western media has been, “What will happen to the women of Afghanistan?”

Indeed, this is an important concern that merits international attention. The Taliban has already imposed many restrictions on women.

At the same time, however, much of the Western media coverage appears to be reinforcing the idea that the U.S. military intervention helped expand the rights for Afghan women, while erasing the impact of years of resulting corruption and violence on their lives.

This framing echoes similar post-9/11 calls to action by many well-meaning Americans on behalf of Afghan women. Pundits continue to ask, did Biden, the U.S. and its NATO allies abandon Afghanistan and its women too soon?

As Afghan American women scholars, we are concerned that this rhetoric presents Afghan women as victims in need of saving, suggesting all women experience life in Afghanistan the same way, without accounting for their activism and political resistance.

We know through our research, advocacy and experiences that a diverse spectrum of women-led groups are fighting for human rights, both now and historically.

Do Muslim women need saving again?

Western colonial powers have a long history of appropriating women’s rights movements in the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia to serve their own geopolitical interests.

Indian scholar Gayatri Spivak was among the first to write about this phenomenon, in reference to British rule in India. In her 1988 essay, she explains how this white savior rhetoric was used to justify Western rule in the name of liberating Muslim, Hindu or pagan women from their “repressive” societies. She described this savior disposition as “White men saving brown women from brown men.”

Scholar Leila Ahmed described this dynamic in her 1992 book “Women and Gender in Islam,” when she notes instances in which imperial British agents in Egypt used women’s rights as a rhetorical device to further their colonial rule, while undermining those rights through the violence of colonial occupation. One example that Ahmed cites is Lord Cromer, the British consul-general of Egypt, who supported Egyptian women’s rights but condemned the suffragist movement at home. He also supported viceroys who were conservative-leaning and espoused anti-women and anti-gay laws.

Anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod in her 2013 book “Do Muslim Women Need Saving?” also cautions against the savior narrative, which she argued reduces Muslim women to a monolithic group who are all repressed by a draconian version of Islam, and in need of some form of militarized intervention, packaged as humanitarianism.

Women’s movements in Afghanistan

Afghan women, just like women of any nationality, cannot be generalized into a singular category. They have a plurality of aspirations, commitments and visions for the future shaped by their socioeconomic identities, religious affiliations or lack thereof, location in the country and ethnic identity.

Afghan women’s rights movements and organizations are also far from monolithic. They range from communist to secular, and moderately religious to more religiously conservative.

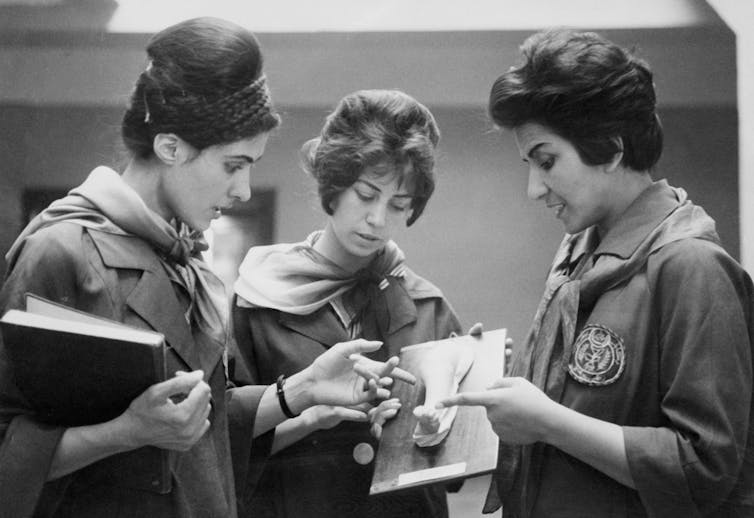

Staff/AFP via Getty Images

In the 1960s and 1970s, Afghanistan underwent a series of liberal reforms started by the government and social works programs that radically increased the active participation of women in arts, culture and politics.

The women’s movements were emboldened by the 1964 ratification of the equal rights amendment act in the Constitution of Afghanistan. At that time, Afghan women began to demand more rights. Shortly thereafter, women began protesting against veiling, which had been socially mandated. The government subsequently worked toward easing the restrictions.

During the Soviet-Afghan War and occupation that lasted from 1979 to 1989, many Afghan women fought and demonstrated against the Soviets, despite being targeted, beaten or killed for their activism.

Two of the most prominent women who were killed for their resistance were Nahid-i Shahid, often known as Nahid the Martyr; and Meena Kamal, the founder of the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan, an organization founded in 1977 in opposition to foreign interference in Afghanistan and corruption in the Afghan government. Shahid was killed by the Soviet-backed puppet regime after protesting the Soviet occupation in 1980. Kamal is said to have been assassinated by a Jihadi leader in 1987.

In recent decades, women professionals used their skills as leverage against repressive edicts. The Taliban, for example, in 1996, was forced to reinstate Suhaila Siddiqi, a female heart surgeon, so she could operate on members of the group.

In the post-9/11 era, U.S. military intervention was coupled with development aid designed to revitalize Afghan society, including women’s empowerment. Many women participated in new educational and professional initiatives, as well as development projects in the arts, media and athletics.

By 2003, in the first elections following the ousting of the Taliban, a U.S. and United Nations mandate in the post-9/11 Afghan Constitution required that women comprise 25% of the Parliament and occupy positions as heads of ministries and governorships.

US military

Over the past two decades, the political clout of the Taliban and other warlords and extremists in Afghan society has been strengthened, with real consequences for women.

In spite of countrywide protests, the U.S.-backed Afghan government invited many of the same leaders and warlords that the Taliban had displaced back to power. These warlords wreaked havoc on the population by using their government positions as fiefdoms to grow their base and to divert international funding to themselves.

Increasing corruption reduced the efficacy of the development projects and undermined the gains made. As media reports pointed out, while the lives of some women in urban areas, especially Kabul, improved, those of women in other parts of the country became unbearable. Many women in rural areas were subjected to constant drone surveillance, night raids and aerial bombings.

The Taliban, similar to their first ascent to power, promised to rid the country of the warlordism and kleptocracy in the U.S.-supported government. With their harsh interpretation of Islam, they also brought back restrictions on women’s freedoms.

The path forward

We argue that it is important to remember the work of many Afghan women reformers and human rights activists over the last 20 years so as to better support their aspirations for social transformation.

Many Afghan women, such as Shaharzad Akbar, chairperson for the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, Fatima Gailani, director of the Red Crescent Afghanistan, Malalai Kakar, the head of Kandahar’s Department of Crimes against Women, Fawzia Koofi and Malalai Joya, both former members of Parliament and women’s rights activists, as well as Suraya Pakzad and Habiba Sarabi, also women’s rights activists, have dedicated their lives to working for women’s rights.

NurPhoto/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Afghan women are not and never have been passive victims who need to be saved. They have a rich history of resistance and political dissent. It is important for the global community to listen to their voices so as to support Afghan women’s aspirations for a better future.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]![]()

Wazhmah Osman, Assistant Professor of Media Studies and Production, Temple University and Helena Zeweri, Assistant Professor of Global Studies, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.