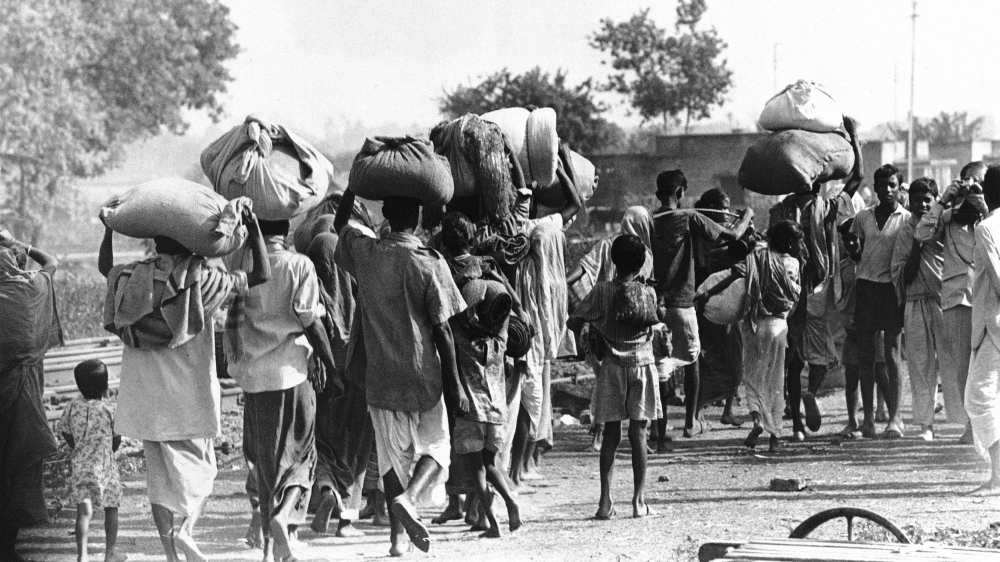

In Bangladesh, 1947 is a distant memory, erased by the much fresher bloody ones of 1971 [File: AP Photo]

by Saikat Majumdar and Sandip Sarkar 29 June 2020

Abstract: Amitav Ghosh’s novel, The Shadow Lines, focuses on the continual diagnosis towards the distemper of partition creating the highest trauma in individual’s lives which caught in a world of flux; where new nations are re-imagined and old identities had arbitrarily redrawn by new notions of national identity. It causes cultural and physical displacements from old contexts into a new matrix. The problem of partition looms large as aggravated assault as the displacements take place with travel and immigration, fuelling religious agitation and bringing about their kinds of alienation and heartbreak. By “cracking of axis and center” the plot of the novel undoubtedly illuminates the darker corridor of the past and the long shadows in the present. Within the connected personal stories which gradually making national sense and a queer sense of border and boundaries, eccentric political identity and citizenship eventually to wider implications free from the intention to see the home on the other side of the border irrespective of enemies and space by upholding the banner of the all-transcending concept of humanity through universalization of ‘Vasudeva Kutumbakam.’ Tha’mma, the grandmother irrevocably believes about the real and concrete boundaries of the partition till she undertakes her pilgrimage to her real home finally brings her disillusionment. This present paper, from the vitriolic vehemence of the post-riot period, tries to interpret those facts of ‘yet undiscovered irony’ felt by the characters, especially by Tha’mma.

For years, various compositions, literary genres, books promulgating refugees’ feelings of rootlessness from East Bengal had multiplied. Their reminiscence or nostalgia for Motherland has been reflected in the poems of Rabindranath Tagore, Jibanananda Das, and so on expressing their long-cherished dream either to bow their head to the feet of Motherland or confessing the intoxicating wish to take birth in his motherland again. They have all portrayed their villages as a picturesque entity where mirth and peace went hand in hand. In pre-partition days there was no major problem between Hindus and Muslims in the rural areas of Bengal till the second half of the 1940s. Things, however, changed suddenly and took a violent turn after the Great Calcutta Killings of August 1946 and the partition of 1947. The impact of the killings polluted the sacred and ‘crystal clear water’ (Anand:1935) of the river ran once upon a time in East Bengal, which ultimately forced Hindus to flee from their beloved homeland. It remains no longer ‘a place where there was no border between oneself and one’s image in the mirror’ (TSL.29). Against this backdrop, the story of The Shadow Lines revolves around the diasporic potential of East Pakistan after the partition. The very pivotal character Tha’mma attains an unprecedented experience of rootlessness which curved out a new passage, a newly formed psychological concept of the home which she feels from the other side of her native home in Bangladesh.

The concept of ‘root’, ‘home’, ‘rootlessness’, and ‘homelessness’ are keystones in the diaspora. In Western concept, ‘home’ is “an imagined idealization of notions such as privacy, intimacy, exclusiveness, secrecy, sheltering, and even sanctity. Rather than a space of a fixed functional characterization, the home is a space of relationships and experiences of many, often contested options, and a meaningful nucleus for the living self” (Blunt and Dowling, 2006; Fenster, Forthcoming; Massey, 1996; Valentine, 2001). Home is an idea that seamlessly enters the material of site and space with an abstraction of family. It is a fundamental element of human life above all in the sense of shelter, protection, security, and it is bound up in an expression of objections to how the world should be dealt with. Most appropriately, definitions of home refer to identity, nostalgic memory, and imaginative sentiments: “the home is a material and an affective space, real or imagined, that is formative of personal and national identity and shaped by everyday practices, lived experiences, social relations, memories and emotions” (Peil, 2009:180). “It is also a space of paradoxical experiences and relationships, such as belonging and alienation, intimacy and violence, wish and fear, that lie at the heart of human life” (Blunt and Varley 2004:3). So, loss of home or departure of home means loss of self, farewell to the idealization of imagined notions, domestic attitudes, responsibilities, multi-layered emotions and well sanctified as well as self sanctioned space- a “domicide”-“the planned, deliberate destruction of someone’s home, causing suffering to the dweller”. Similarly, ‘root’ is not merely a place, a domicile, or an abode but a powerful cultural signifier that constitutes the signified of the opposite of rootlessness, uprootedness, etc. If the root is the ultimate social, historical, nationalistic, and patriotic signifier then rootlessness is a kind of transcendental signified of these and more interestingly vice-versa. Thus, root and rootlessness are carnivalistic (Bakhtin:1963) in its presence as well as binary in nature. Generally, the term rootlessness is the way of foregrounding various terms in literature as refugee, vagrant, errant, maverick, gadabout, an evacuee. But the term should be understood or analyzed as a state for which various political practices, not the rootless are responsible. It conveys more a style of subjugation or victimization which includes children, women, men, and even pets. In the present day, the word rootlessness is more acidic where the term root is more nostalgic. In the novel The Shadow Lines, the characters are well corroborated with the root from different psychological level and the concept of the home stands in the allegorical relationship with Nation. Home as an anchor keeps one rooted in his/her self. But as unseen destiny would have preordained some other way, many important characters in the partition and diasporic fictions lose the protection of the homeland and are flung onto an alien world. Certainly, the result is tragic and the concerned characters find themselves in a severe crisis – interpersonal as well as intrapersonal and The Shadow Lines is unmistakably an exemplary text to have the entire tragic crisis.

There are two sets of characters: Tha’mma, Tridib who are forcibly uprooted from their native compelled to consider other places as their root and Ila, the unnamed narrator, Robi, May- some among them are completely culturally uprooted and others are fighting to cling with and trying to redefine their root. In the first group, Tha’mma is a character whose concept of root brings multifarious rhizomatic forms of love- love for native, or for relatives, love for country, love for freedom, and above all her thought of loving childhood. Ila, on the other hand, is never aware of her root culture. She loves to float in the anonymous crowd of ‘global nonspace’ (Connor, 2004). Her love and fondness for London deny her to consider her Indian root and for her deep-rooted faith for British culture made her culturally bankrupted and uprooted in the eye of Indian.

Ila’s quest for freedom has its root in her rootlessness. Ila is not only uprooted from her family, she even doesn’t have a basic sense of belongingness. Ila has never seen stability in her life, she was always moving from one country to another and from one school to another. These countries are quite different from one another. But the people who inhabit them are the same everywhere. The segregation and humiliation she faces on her being a brown-skinned, dark-haired Indian are the same everywhere. At airports she feels as:

Running around the airport to look for the ladies not because she wanted to go, but because those were the only fixed points in the shifting landscapes of her childhood. (TSL. 13)

Ila, to survive in these different environments, escapes into an imaginary world. In her search for freedom, Ila gets deeply wrapped in an illusory relationship with Nick Price because, just like Ila, Nick also lives in a world of illusion. Everything about him is illusory. Ila endures his extra-marital affairs because she discovers: “That the squalor of the genteel little lives she had so much despised, was a part too of the free world she had tried to build for herself.” (TSL 67) Ila is incapable of free herself from the various intertwines of life because instead of accepting reality, she is running away.

Ila in The Shadow Lines, has lived most of her life in London and she thinks that London offers shelter against the oppression of Indian society. She would write to her cousins back at home about the many incidents with friends she had in school, which were all made up of the stories of her segregated life. The narrator ponders on how-

Ila who in Calcutta was surrounded by so many relatives and cars and servants that she would never have had to walk so much as the length of the street… had to walk alone because Nick Price was ashamed to be seen by his friends, walking home with an Indian. (TSL.76)

Again Ila, the worst victim of the diaspora condition, could neither stay in India nor could she find happiness in London. She had to frame stories so that her cousins would not make fun of her. The character delineation of Ila has close parallelism with the character of Piyali Roy in The Hungry Tide (Ghosh:2004). Piyali has lived in America since the time she was one year old. She claims as an American rather than an Indian. She comes to Sundarbans to conduct a survey of marine animals with no intention of living in the country. However by the end of the story – “you know, Nilima,’ she said at last, ‘for me, home is where the Orcaella arc: so there’s no reason why this couldn’t be it.'(Ghosh: 2004) Between these two nonadjustable heads, Piyali appears to be complacent with the good and bad in both India and America, Ila strictly believes that India is bad in respect of London. While Piyali does not confine her idea of home just in America but anywhere where her work takes her accordingly, Ila on the other hand, firmly believes that London is her home even though London keeps refusing her. Ila is continuously trying to adjust herself in London but the reason she is not able to adapt to this cosmopolitan society is that she is not ready to be a part of it. She can only do this when her vision will be broadened beyond London society. According to Coomaraswamy, “A single generation of English education suffices to break the threads of tradition and to create a nondescript supercritical being deprived of all roots”.

Tha’mma is running away from her past- for the quest of her umbilical pain where Ila is running from the quest of the present itself, which leads her deep into the enmesh of illusion. If Ila is a giddy fleeting girl intent on living fully in the present and wants an extreme form of freedom, then Tha’mma hankers after freedom. From her present state of identity and chasing after freedom to get back her national identity. For both of her freedom she even might become a killer or murderer and would like to go to the furthest extent to accept martyrdom by sacrificing her blood, like others’ father’s blood and brother’s blood. The concept of ‘home’ looms large as abstract once when she steeped in nostalgia in Kolkata further becomes concrete and individual during her “Coming home”. It is a culmination of long past endeavors, sacrifice, and devotion. Of all cults, among all sacred phenomenon, her home, ancestry is the most legitimate one, the most ideal one.

The character Ila is torn between Thamma’s deep-rooted sense and belief of middle-class education and culture with her sense of rootlessness. She rejects her roots, her acquaintance, her cars, and servants in India and seeks an identity for herself all alone in an unknown land because she wants “to be free.” “Then she pushed me away and waved at a taxi. It stopped, and she darted into it, rolled down the window, and shouted: Do you see now why I’ve chosen to live in London? Do you see? It’s only because I want to be free. Free of what? I said. Free of you! she shouted back. Free of your bloody culture and free of all of you.” (TSL.67)But this is not the freedom according to Tha’mma. “It’s not freedom she wants, said my grandmother,… She wants to be left alone to do what she pleases; that’s all that any whore would want. She’ll find it easily enough over there; that’s what those places have to offer. But that is not what it means to be free.”(TSL.35)

According to Tha’mma this is the way of two worlds where people can pursue their liberty. But Ila suffers from a different kind of want. She forms an illusory world where there is no particular definition of freedom to particularize other things in the name of rigid culture or taboo. She wants to enjoy her every inch of action only in the name of the act, not in the parameter of freedom, liberty irrespective of culture or country. Such type of world is evident in the story of Magda Doll and Nick narrated by Ila. Magda is a doll and her ‘make-believe’ child. She is Ila’s other and her alter-ego. In Magda we can find mixed racial features. She has blonde hair and blue eyes, suggesting Ila’s desire to be an English girl. Surprisingly, though Magda is English in appearance, she is ill-treated as a subaltern Asian and is beaten by Denise, her classmate. Through these stories of cultural, religious, racial, and geopolitical boundaries are blurred. She could neither stay in India nor finds` happiness abroad. She had to frame stories so that her cousins back at home would not make fun of her.

May Price is also one of those characters in the novel who is trying to seek freedom. May is a free woman, free in the sense that she lives on her own, takes her own decisions. May is blinded by her love for Tridib in a very strange way. She feels guilty about being responsible for his death. She even begins to question her love for Tridib because of that incident: “I don’t know whether everything else that happened was my fault, whether I’d have behaved otherwise if I’d really loved him.”(TSL.175)She is too afraid to face the facts of Tridib’s death. She is unable to show the happenings of that day in Dhaka to anybody because she feels that nobody would have been able to understand her pain. But she reveals the fact to the narrator, who she knows loves Tridib as much as she does.

The unnamed narrator has made Tha’mma the fulcrum figure whose character helps to bring out the proper synthesis from the thesis and antithetical renderings. She was the penchant believer about the person’s formation of identity out of nation and sacrifice towards the nation. Her concept of nation rendered in terms of achievement even through bloodshed. Her militant nationalism looms large when she exhorts the young narrator about bloodshed for the nation. She says:

It took those people a long time to build that country; hundreds of years, of wars and bloodshed. Everyone who lived there has earned his right to be there with blood; with their brother’s blood and their father’s blood and their son’s blood. (TSL. 77)

Her expression and idea of a nation undoubtedly reflect as Ernest Renan explains:

The Nation is the culmination of a long past of endeavors, sacrifice, and devotion. Of all cults, that of the ancestors is the most legitimate, for the ancestors have made us what we are. A heroic past, great men, glory…this is the social capital upon which one bases a national idea. To have common glories in the past and to have a common will in the present.

Her overstrung commitment to violence for national unity is the outcome of her sense of insecurity, the outcome of the partition unavoidable, and unmanageable. According to her not only psychological strength but also ‘strong body’ is needed to form a strong nation. ‘You can’t build a strong country, without building a strong body.'(TSL. 8)

Thus, Tha’mma builds up a concept of the nation which is similar to the locale of a physical and psychic level. As colonialism and partition have snatched from her both nation and home, it is her virulent sense of nostalgia which will bring her back the both from metaphorical level. She wants to see her feet standing beside the tombs of national saints and domestic monks to whom she will be offering her utmost obeisance and deep salutation. It is no house, it is the root home where her prayer for divinity and quest for identity is eventually resolved and answered. The words of Jon Mee (2003: 109) are worth quoting here, ‘Tha’mma sees national identities, not in terms of imagined communities, but [as] a deeply rooted connectedness to a place borne out of the blood sacrifices of generations’ Historical reality seems to mock Tha’mma’s belief in the importance of family ties. Stuart Hall’s Familiar Stranger (2017) takes us to the heart of Hall’s struggle in post-war England: that of building a home and a life in a country where rapidly, radically, social landscape were transforming, and urgent new questions of race, class, and identity were coming to light. He emphasizes that ‘no single, universal theory of nationalism is possible. As the historical record is diverse, so too must be our concepts’ (Hall 1993: 1).

Born in Dhaka, Thamma migrated to Mandalay because of her husband’s profession. After her husband’s death, she joined a school in Calcutta as a teacher. This provided her with stability in her rootless existence. While in Moulmein and Mandalay she lived in “a succession of railway colonies” (TSL. 124) and her life became uneventful. To her “nothing else in that enchanted pagoda-land had seemed real enough to remember (TSL. 124) apart from hospitals, railway stations, and Bengali Societies. Interestingly, in this, she resembles her opposite, Ila, whose peripatetic lifestyle forbids her to attach herself to any place. The bloodshed of the Partition severs Thamma’s connection with her ancestral home in Dhaka. However, a chance meeting with one of her kin makes her know that her nonagenarian Jethamoshai still lives in their house at Jindabahar Lane in Dhaka. What is more, she was horrified to learn that their whole house was occupied by Muslim refugees from India. Throughout her life, Thamma never displayed much family feeling. In fact, “she was extremely wary of her relatives; to her, they represented an imprisoning wall of suspicion and obligations” (TSL. 129). However, consanguinity propels her to dismantle this “imaginary barrier” (TSL. 129) and she decides to travel to Dhaka to bring her Jethamoshai back to Calcutta. With the sheer sense of rootlessness and alienation originally from Dhaka, she clings on to her life in the past and remembers places like Shadow-Bazar, the Royal Stationery, and the jewelry shop with great clarity. She is unable to sever her bonds with the past. She will be carrying an exterior of toughness and self-reliance, yet she goes through nostalgia and pain in her heart. Beneath that outer surface is a heart that bleeds and longs for a return to the land of her birth. For her ‘home’, her indigenous identity, her ‘nation is a soul, a spiritual principle” (Renan, 1995: 56)With such kind of zeal, wiping out all the differences of grammatical categories and functions Tha’mma, discards research as a “lifelong pilgrimage” (TSL.7) was maddened by the ‘secret lore’ to start her long-cherished pilgrimage to her temple- ‘home’, her space of ‘actual self’ to bow in front of her God. The concept of ‘home’ to Tha’mma is the spiritual soil upon which her soul is sub structured despite the threat of the ‘Muslim Dhaka’. She considers her home as a reservoir of memory, memory between the past and the present, a memory between ‘going away’ and ‘coming home.’

For her, travelling to Dhaka was different in the pre-Partition era when she could “come home to Dhaka” (TSL.152) when she wanted. The fact that her journey to Dhaka is not only physical but also epistemological was revealed when the young narrator teases his grandmother out of her thoughts: “How could you have ‘come’ home to Dhaka? You don’t know the difference between coming and going” (TSL.152)! Years later the mature narrator realizes that his grandmother’s journey not only destabilizes her fixed notion of “home” but also exposes the faults of a language system:

Every language assumes a centrality, a fixed and settled point to go away from and come back to, and what my grandmother was looking for was a word for a journey which was not a coming or a going at all; a journey that was a search for precisely that fixed point which permits the proper use of verbs of movement.” (TSL.152)

All the other binaries like love and hatred; Hindu-Muslim, right and wrong, life and death are merely insignificant tropes to her. Her home, her native soil which furnishes the substratum, the field of struggle, an everlasting appeal of her soul to which no material well suffice for it. Like Ila she is in a continuous flux of places and whose wandering lifestyle forbids her to attach herself to any place except the only place from which she belongs to. Partition, as a trauma that congeals fear, nervousness, panic all into in absolute silence, for which The Shadow Lines seeks to find an in language, a required process of lamentation and complaint but never able to divide the memory of people or encourage absolute oblivion.

Tha’mma’s visit to Dhaka could be said to be her error in judgment and she had to pay a toll of human life. As worship and pilgrimage seeks sacrifice, the pilgrimage by Tha’mma claimed the life of Tridib, Jethamoshai, and Khalil, in the communal frenzy when they tried to return to India from Dhaka after convincing Jethamoshai to accompany them. This tragic and pathetic incident has its bearing on the psyche of Tha’mma, for her perception of relations changes drastically indeed. This lady, who has been talking about peaceful co-existence among people of different countries hence, begins advocacy about a kind of strike against ‘them’ to keep Indians safe. She donates her gold chain to the fund for war. When the narrator questions her about her decision of donating the chain, she emotionally says, “We have to kill them before they kill us; we have to wipe them out” (TSL. 237).

Thamma’s culminated and idealized concept “home” turns confusingly esoteric when her alienation from her homeland and the first question that she was prompted to ask, after landed Dhaka, confounded by her present surroundings, is “Where’s Dhaka? I can’t see Dhaka” (TSL.193). Thamma’s Dhaka is confined in the localized surroundings of her ancestral home in Jindabahar Lane which had “long since vanished in the past” (TSL.193). This past/present disjuncture leads to her confusion. Her quest for the idyllic, pre-partitioned Dhaka of her childhood is projected as a nostalgic return to her ancestral roots.

Compelled by circumstances, she now realizes the gravity of her predicament that she has “no home but in memory” (TSL.194). Her heavy heart was preponderant by Tridib’s teasing remark that “you are a foreigner now, you’re as foreign here as May – much more than May, for a look at her, she doesn’t even need a visa to come here” (TSL195). Tha’mma’s final disillusionment occurs when the car in which she was returning along with Jethamoshai in a rickshaw was attacked by some frenzied rioters. Tridib rushes out to save the old man but both of them are brutally killed along with the rickshaw-puller Khalil. Thamma’s ancestral birthplace is also the city of the fanatic rioters which now is transformed into the split space of home/no home. Tridib’s violent death instills in her a hatred for “them” to destroy that brutally which “had evolved slowly, growing like a honeycomb, with every generation of Boses adding layers and extensions, until it was like a huge, lop-sided pyramid, inhabited by so many branches of the family that even the most knowledgeable amongst them had become a little confused about their relationships”(TSL.121) called “Home” where she thinks she could find security, stability and a sense of belongingness, a feeling of completeness. Th’amma is eager to undertake her journey to Dhaka which reveals her eagerness to return to her actual home. But a series of adventures that she encounters makes her realize gradually that she is different from other people of Dhaka. Her memory is distinct from the present unfamiliar Dhaka. Th’amma’s present situation is aptly comparable just like the character Tara in The Tiger’s Daughter (1971). To Th’amma as Dhaka and to Tara Calcutta appears to “exert its darkness over her”. In both of their journey, they are flooded and spilt off old memories.

The contradiction between Thamma’ s ‘going’ and ‘coming’, home and abroad, local and national identities surfaces in her resolution to-bring her Jethamoshai to “where he belonged, to her invented country” (TSL. 137). However, Thamma’s glorification of the myth of the nation was punctured by her senile Jethamoshai’s stubborn refusal to migrate:

I don’t believe in this India-Shindia. It’s all very well, you’re going away now, but suppose when you get there they decide to draw another line somewhere? What will you do then? Where will you move to? No one will have you anywhere. As for me, I was born here, and I’ II die here. (TSL. 215)

His words show the very expression of V.S. Naipaul: “There could be no going back; there was nothing to go back to. We had become what the world outside has made us; we had to live in the world as it existed.”( A Bend in the River:1979)

Along with Thamma’s conceptions of a home as a place of greatest stability and eventual coherence thus shattered after she receives a further setback when her son exposes the limits of her exclusionary nationalism. Her naïve belief in the existence of borders corresponds with Anderson’s conceptualization of the nation as “limited” with “finite, if elastic boundaries, beyond which lie other nations” (1983: 16). When she expresses her curiosity to see the border between India and East Pakistan from the plane, her son humorously asks her whether she thought that the “border was a long black line with green on one side and scarlet on the other, like it was in a school atlas” (TSL.151). When she learns that neither trenches nor soldiers with guns pointing at each other separate the two countries but there are only green fields with no distinct demarcation zones, she discovers the limits of her brand of nationalism.

Eudora Welty’s observation, made in another context in the article “Place in Fiction,” seemed quite relevant here:

There are as many ways of seeing a place as there are pairs of eyes to see it. Sometimes two places, two countries are brought to bear on each other … and the heart of the novel is heard beating most plainly, most passionately, most personally when two places are at the meeting point.

Dhaka seemed the crucible in which the relativistic discourse of the novel is tested and clarified. It is here that the heart of the novel beats most fervently, which, with the changing contexts of the three dimensions, seems to become four-dimensional at least for the grandmother, who reconciles herself only when she reaches the Dhaka of her nostalgic past. As she comes to realize, as Saskia Sassen in Losing Control (1996) points out “the world is not a system of neatly organized, perfectly cropped, homogeneous entities: it is diverse, dynamic, and ‘messy,’ with a mismatch between cultural and political boundaries”. The well-nourished logocentric idealism of Tha’mma proved catastrophic. Her logos nation is lost in the airport as well as in her ancestral, while the logos of nationalism and nationalistic zeal passed away with the death of Tridib and Jethamosai.

However, Th’amma’s realization gets reflected in the words of Ayelet Shachar in The Birthright Lottery (2009):

The accidental lottery of birth assigns individuals to a specific territory, and geographic boundaries can determine whether an individual’s life experience will be one of peaceful cohabitation or ethnic cleansing, abundant food supplies or mass starvation, economic opportunity or dire poverty, inclusion or exclusion.

Thus, The Shadow Lines presents its character’s journey- very ‘strangest journey; a voyage into a land outside space’, a pilgrimage to the temple devoid of God, ‘an expanse without distance’, a rhizomic quest for root.

—————————-

References

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 1991.

Auradkar, Sarika. Amitav Ghosh: A Critical Study, Creative Books Publication:

New Delhi, 2007.

Chatterjee, Partha. Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World : A Derivative Discourse? (Delhi : Oxford University Press, 1986).

Gellner, Ernest. Nations and Nationalism. Ithica, NY: Cornell University Press.1992.

Ghosh, Amitav. The Shadow Lines (New delhi: Ravi Dayal, 1988).

Guia, Aitana. The Concept of Nativism and Anti-Immigrant Sentiments in Europe. European University Institute. 2016.

Hall, Stuart. ‘The Local and the Global’: Culture, Globalization and the World System. Ed. Anthony D. King, University of Minnesota Press,1997.

Hobsbawm, Eric. Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990)

Khair, Tabish. Amitav Ghosh: A critical Companion, Delhi: Permanent Black. 2003.

Malhotra, Meenakshi. Teaching ‘The Shadow Lines’ in Amitav Ghosh: Critical Perspectives, Pen craft International: Delhi, 2003.

Mukherjee, Meenakshi. “Maps and Mirrors: Co-ordinates of Meaning in The Shadow

Lines. Educational Edition. Delhi: Oxford UP, 1995.

Rajan, Rajeshwari. The Division of Experience in The Shadow Lines by Amitav Ghosh, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Roy, Rituparna. South Asian Partition Fiction in English: From Khushwant Singh to

Amitav Ghosh. Amsterdam. Amsterdam University Press: 2010.

Sassen, Saskia. Losing Control? Sovereignty in an Age of Globalization (New York: Columbia University Press), 1996.

Shachar, Ayelet. The Birthright Lottery: Citizenship and Global Inequality (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Sharma, I. D. Amitav Ghosh: The Shadow Lines, Prakash Book Depot: Bareily, 2010

Smith, Anthony. The ethnic origins of nations; Basil Blackwell Inc., NewYork (1998)

Smith, Anthony. National Identity. London: Penguin Press. 1991.

Trivedi, Darshan. “Where is Dhaka?” Interpretation Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines. Ed.Bhatt and Nityanandam. New Delhi: Creative Books, 2000.