(RNS) — Where does the history of Muslims in America begin? With enslaved African Muslims brought to the U.S. in the 1600s? In the 1930s, when the Nation of Islam was established by Wallace Fard Muhammad in Detroit?

Is it defined by the growth of American Muslim communities after the 1965 immigration act opened the U.S. to Asia? By the establishment of Muslim institutions? Is it when we got here, or when we were seen by the rest of American society?

Wherever we trace our beginnings, Muslim Americans are still seen as people who come from elsewhere. More than 20 years after 9/11, American Muslims are often still asked where we are from or sometimes told to “go back to where you came from.”

A new six-part documentary film series debuting on PBS digital this week answers some of these questions and addresses some of these misunderstandings, exploring the deep history of Muslims in America through the stories of six dynamic individuals who will be familiar to many Muslims and non-Muslims: immigrants, native-born converts and those who were brought against their will.

Each episode of “American Muslims: A History Revealed,” hosted by Al Jazeera presenter Malika Bilal, Slate writer Aymann Ismail, and NPR correspondent and ABC News contributor Asma Khalid, introduces a different Muslim American’s story: a South Asian immigrant married to a Mexican American; a Black woman who found Islam after moving to Chicago; and a Syrian-Lebanese Muslim who migrated through Canada and helped establish the first purpose-built mosque in the most unlikely of places.

Journalists Malika Bilal, from left, Aymann Ismail and Asma Khalid host episodes of “American Muslims: A History Revealed.” (Image courtesy American Muslims)

My own American journey flourished in Grand Forks in eastern North Dakota among a handful of scattered Muslim families. My father was a professor at the University of North Dakota Medical School and faculty adviser to the university’s tiny Muslim Student Association. As such, I was especially interested in Ismail’s segment on Mary Juma, the Syrian-Lebanese woman who came to the U.S. in the early 1900s to settle in the now sleepy town of Ross, North Dakota, population 90 (give or take), on the opposite side of the state from where I grew up.

There her community built the first “purpose-built” mosque in the United States — a place that was erected as a mosque, not a repurposed church or other building. “It took me totally by surprise,” Ismail told me when I called him about the episode.

Me too. Back in the 1980s and ’90s, our campus group had no mosque of its own, purpose-built or otherwise. We met for Friday and Eid prayers at the university’s International House or the community hall of a local church. I grew up believing that Cedar Rapids, Iowa, was the U.S.’s first dedicated mosque building — my family had visited it when I was a young adult. (The mosque in Juma’s town of Ross fell apart in the 1970s.)

In another episode, about Mir Dad, a Punjabi Indian who immigrated to the American Southwest around 1917, Yale University historical anthropologist Zareena Grewal talks about how Muslims built community across religious and ethnic differences.

Dad’s story, told by NPR’s Khalid, shows how South Asian immigrants connected with Mexican American immigrants to fight exclusionary immigration legislation and to change attitudes toward brown and Black immigrants at the turn of the 20th century. Khalid interviewed several of Dad’s adult grandchildren, who grew up in a Mexican-Indian-American-Muslim household.

In such multi-hyphenated families, ensuing generations didn’t always fully practice Islam, if at all, which caused consternation among some Muslims. “When we look at these early migrant communities, oftentimes people will be surprised that their children were not Muslim or their grandchildren were not Muslim, and so they see them as failing to propagate the faith somehow,” said Grewal. But “rather than looking at the children as the test, we look at institution building. So whether it be mosques or restaurants, ethnic institutions, newspapers, they produced all these really important institutions that were absolutely critical to the continuity of Islam in this country.”

The Great Migration of Black Americans northward to escape Southern oppression becomes intertwined with the founding of Ahmadiyya Muslim communities and the Nation of Islam. Bilal helps tell the story of Florence Watts, one of four women we see in a photo taken on Chicago’s South Side in the 1920s wearing an early form of hijab.

Watts’ story is carefully traced through census records and documentation of her conversion to the Ahmadiyya sect of Islam in a 1922 list of “New Converts” published in the Moslem Sunrise, a monthly newspaper founded in 1921 by Mufti Muhammad Sadiq of the Ahmadiyya community.

“You can’t tell the story of America without the story of Black people,” said oral historian Zaheer Ali, who is an executive producer of the series. “And you can’t tell the story of Muslims in America without the story of African American Muslims,” including enslaved Africans and converts to the Nation of Islam, Fard Muhammad’s Islamic and Black nationalist movement founded in Detroit in 1930.

“I think for people who are drawn to Islam during this period (when the Nation of Islam was established) … many of them (were drawn by a) sense of ancestral legacy, that Islam was a recovery of a lost history that had been disrupted through slavery,” Ali said.

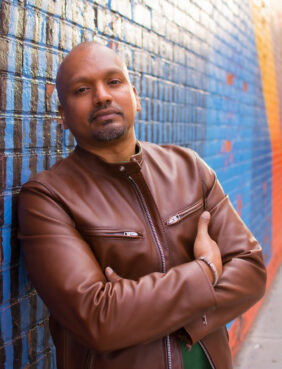

Zaheer Ali. (Photo courtesy American Muslims)

“But there’s also something new,” he added. “Islam, as it is presented in this moment, is familiar enough in the spiritual sense, but new enough to introduce a different kind of political discourse, a discourse that challenges racism.”

As fascinating as the storytelling is, I wondered if audiences, including Muslims, are ready to accept Islam as a part of America’s rich history or if viewers will see the series as another attempt to prove Muslims’ “Americanness,” a theme so heavily promoted after 9/11 that many American Muslims reject it.

Or does that even matter?

I tried to explain this concern to Ismail and asked if he felt the same. “What I find to be so exciting about this project is not that it teaches Muslims … that it’s ok to be American. We know that already. To me the usefulness of a project like this — among many other reasons why it’s important — is the ammunition it gives us when we are interfacing with that part of America that still questions us. (Muslim Americans) don’t owe anyone anything, but if people have questions, they can watch this.

“What I love about this country is that we get to choose our heroes,” Ismail said. “And we have such a swath to choose from. And the very patriotic part of America who idolizes Thomas Jefferson now has to reckon with the fact that Thomas Jefferson owned and kept a Quran in his library.”

source : rns

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published