More robust agreements to share the precious resource will result in a win-win for both countries.

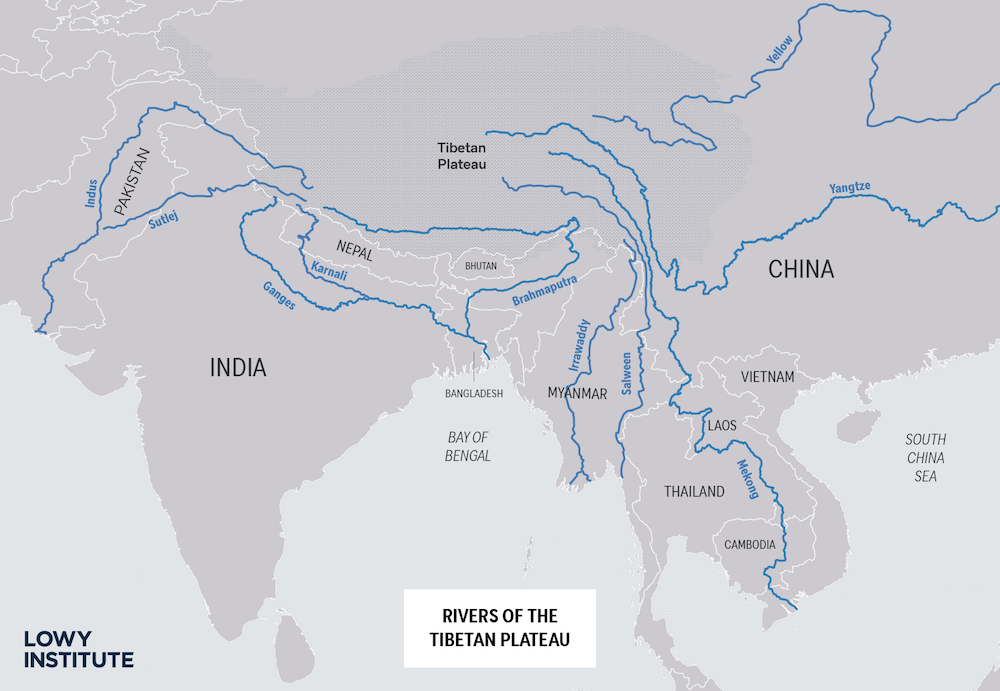

India and China are connected by a number of rivers that flow into each other’s territory, notably the Brahmaputra, Sutlej and Indus. These rivers are vital to both nations because they supply water that is used for drinking, irrigation and the development of hydropower. However, the division of water resources between the two nations is a complicated issue that is frequently exacerbated by political conflicts.

The fact that China controls the upstream portions of all the major rivers that flow into India is one of the most significant obstacles. This provides China with a considerable advantage in controlling water resources. On the Brahmaputra River (Yarlung Zangbo), China maintains three hydrological stations: Nugesha, Yangcun and Nuxia. On the Sutlej River (Langqen Zangbo), data is provided by the Tsada hydrological station.

This information is critical because it aids in the management of potential flooding in the downstream regions, which often occurs when rivers overflow as a result of heavy rains. Following the Doklam standoff on the border of India and China in 2017, China stopped releasing hydrological data on the Brahmaputra, claiming damage to data-gathering sites as a reason. However, as diplomatic relations improved in 2018, data sharing between the two countries resumed, demonstrating that when relations are positive, both sides are more likely to work on matters pertaining to water.

The fact that the two countries do not have a formal water-sharing agreement presents yet another obstacle. They rely, rather, on a collection of memorandums of understanding (MoUs) that are periodically updated. An MoU on the provision of hydrological information on the Brahmaputra River during flood season was signed in 2002 and renewed in 2008, 2013 and 2018. Similarly, an MoU on the Sutlej River was signed in 2004 and renewed in 2010 and 2015. Under these MoUs, China provides India with real-time data on water levels, discharge, and rainfall from hydrological stations on the two rivers during the flood season (June–October). This data is used by India to help manage its water resources and mitigate the risk of flooding.

Both MoUs expired in 2023, but China has continued to supply data on the Sutlej River. The two countries are currently in the process of renewing the MoUs. However, these agreements are not legally binding, and there is no process in place to settle disagreements between the parties. In addition to the MoUs, India and China also have an Expert Level Mechanism (ELM) to discuss transboundary water issues. The ELM has met regularly since 2006, but it has not been able to resolve any of the major disputes between the two countries.

More than 87,000 dams have been constructed throughout China – including in Tibet – many of which are located on international waterways that are shared with India. In 2019, China’s consumption of freshwater had grown to more than 600 billion cubic metres, while India is expected to see a doubling in its demand for water by 2030. More than 120 billion cubic metres of water are lost every year due to leakage from water distribution systems, inefficient irrigation practices, domestic water waste and industrial water pollution.

The absence of an all-encompassing water-sharing agreement between India and China has a considerable influence on downstream regions. Water shortages brought on by China’s upstream control have had detrimental effects not only on agriculture but have resulted in a decrease in the flow of water in the Sutlej River. They have also had a severe impact on irrigation and the generation of hydropower in the Indian state of Punjab.

There are a few things that India can do to strengthen its water position with China. The first is to engage Beijing in diplomatic conversations about the stipulations of the Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses. This convention establishes a framework for the equitable and responsible use of water resources that are shared across international borders.

Second, India should inquire about the built and planned infrastructure on the upper basin of rivers flowing from Tibet into India and request specific details about both. This will assist India in better understanding China’s objectives for water management and help mitigate any potential adverse effects that may arise as a result.

Third, India must collaborate with China to establish a legal agreement for the sharing of water resources. This agreement ought to be founded on the tenets of fairness and reasonableness, and it ought to provide a process for settling disagreements as a part of its provisions.

Fourth, the two countries should improve the functioning of the cooperative mechanism for the management of water challenges. This mechanism has the potential to play an important part in fostering conversation and collaboration between India and China on issues pertaining to water.

The equitable distribution of water between India and China is a difficult challenge but it is one that must be overcome. Both countries stand to gain from engaging in productive conversation and working together to devise a water-sharing system that is long-term and mutually beneficial.