By James M. Dorsey

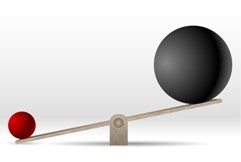

Buried in the Gulf crisis are two significant developments likely to shape future international relations as well as power dynamics in the Middle East: the coming out of small states capable of punching far above their weight with Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, a driver of the crisis, battling it out; and a carefully managed rivalry between the UAE and Saudi Arabia that has weakened the six-nation Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and aggravated suffering in war-wracked Yemen.

Underwriting the battle as well as the rivalry is different strategies of small states, buffeted by huge war chests garnered from energy exports, to project power and shape the world around them. Both Qatar and the UAE project themselves as regional and global hubs that are building cutting-edge, 21st-century knowledge societies on top of tribally-based autocracies.

That, however, may be where the communality in approach ends. At the core of the different strategies as well as the six-week-old diplomatic and economic boycott of Qatar by a Saudi-UAE-led alliance, lie opposed visions of the future of a region wracked by debilitating power struggles; a convoluted, bloody and painful quest for political change; and a determined and ruthless counterrevolutionary effort to salvage the fundaments of the status quo ante.

The differing visions and the two small states’ determination to act on them as a matter of a security and defense policy designed to ensure regime survival made confrontation inevitable.

It is an epic struggle in which Qatar and the UAE, governed by rulers who have a visceral dislike of one another, could in the short and middle term both emerge as winners even if it is at the expense of those on whose backs the battle is fought and considerable damage to their carefully groomed reputations.

Complicating the region’s lay of the land with its multiple rivalries is the fact that at times the interests of the main protagonists both coincide and exacerbate the crisis. For years, the Gulf’s major players supported Syrian rebels fighting the regime of President Bashar al-Assad, yet complicated the struggle by at times aiding rival groups.

Ultimately, however, the opposing strategies that involve the UAE working the corridors of power of the Gulf’s behemoth, Saudi Arabia, whose focus is its existential fight with Iran, and Qatar sponsoring opposition forces, has left the Middle East and North Africa in shambles.

Beyond Syria, Libya and Yemen are wracked by wars. Egypt is ruled by an autocrat more brutal than his autocratic predecessor who has made his country financially dependent on Saudi Arabia and the UAE and has been unable to fulfill promises of greater economic opportunity.

As a result, as small states, like Singapore, debate in the wake of the Gulf crisis their place in the international pecking order and their ability to chart an independent course of their own, Qatar’s brash and provocative embrace of change as opposed to the UAE’s subtle projection of power that shies away from openly challenging the powers that be, may be too risky an approach to emulate.

Nonetheless, the jury on the differing approaches is still out. Qatar has been able to defy the boycott and so far, convincingly reject demands of the Saudi-UAE-led alliance that would undermine its sovereignty and turn it into a vassal based on its financial muscle and an international refusal to endorse the approach of its detractors that many views as extreme, unrealistic and unreasonable.

Taking the long view on the assumption that change is inevitable, Qatar could emerge as having been on the right side of history even if the notion that it can promote change everywhere else except for at home is naive at best. A wave of nationalism with Qataris rallying around their emir in defiance of the Saudi-UAE-led boycott masks criticism of the ruler’s policies that Qataris in recent years vented on social media.

However the Gulf crisis ends, Qatar’s revolutionizing the Middle East and North Africa’s media landscape with the 1996 launch of Al Jazeera speaks to the ability of small states to shape their environment.

The television network’s free-wheeling reporting and debates that provided a platform for long-suppressed voices, shattered taboos in a world of staid, state-run broadcasting characterized by endless coverage of the ruler’s every move. Al Jazeera, despite its adherence to the Qatari maxim of change for everyone but Qatar itself by exempting the Gulf state from its hard-hitting coverage, forced an irreversible change of the region’s media landscape in advance of the advent of social media.

Qatar’s strategy by definition made the Gulf state a target, culminating in its current showdown with its detractors. The Saudi-UAE-led boycott crowns decades of failed efforts to get Qatar to halt its support of the region’s opposition forces, including the Muslim Brotherhood, that advocate alternative, more open systems of government, as well as more militant groups.

If Qatar’s strategy was confrontational, the UAE opted for an approach that granted it a measure of plausible deniability by influencing the policies of Big Brother Saudi Arabia, establishing close ties to key decision makers in Washington, acquisition of ports straddling the world’s busiest shipping lanes, and crafting a reputation as Little Sparta, a military power that despite its size and with the help of mercenaries could stand its ground and like the big boys on the block establish foreign military bases.

In doing so, the UAE successfully exploited margins in the corridors of power in Riyadh to get the kingdom to adopt policies like the banning of the Brotherhood, a group that has the effect of a red cloth on a bull on UAE Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, but that the Saudis may not have pursued otherwise.

The UAE, moreover, by aligning itself with Saudi Arabia rather than antagonizing it, has been far defter in its ability to achieve its goals and project its power without flying too high above the radar.

The UAE’s approach has also allowed it to ensure that significant policy differences with Saudi Arabia on issues such as the conduct and objectives of the Yemen war, a role for the Brotherhood in a Sunni Muslim alliance against Iran, the degree of economic integration within the GCC and the UAE’s thwarting of Saudi-led efforts to introduce a common currency, and Hamas’ place in Palestinian politics, did not get out of hand. Even more importantly, the approach ensured that the UAE’s policies were adopted or endorsed by bigger powers.

At first glance, the UAE’s approach dictated by its determination to resist change would appear to be more sensible for small states. Like in the case of Qatar, the jury is still out.

If a change in the Middle East and North Africa is ultimately inevitable, the UAE is no less vulnerable than Qatar. Crown Prince Mohammed’s obsession with the Brotherhood is rooted in the fact that the group at times enjoyed significant support among Emiratis as well as within the country’s armed forces.

While the rulers of the seven emirates that constitute the UAE under the leadership of Abu Dhabi’s Al-Nahyan family may well agree on the threat posed by the Brotherhood, it remains unclear whether they are equally enthusiastic about Crown Prince Mohammed’s aggressive policies towards Qatar.

“This is about Abu Dhabi asserting its dominance in foreign policy issues because this is not in Dubai’s interest,” said former British ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Sir William Patey.

By implication, Sir Patey was suggesting that unease among the various emirates may be one reason why Abu Dhabi refrained from tightening the screws by closing a partially Abu Dhabi-owned pipeline from Qatar that supplies Dubai with up to 40 percent of its natural gas needs.

The Gulf crisis is not about to end anytime soon. Yet, it has already established that small states need not surrender to larger neighbourhood bullies and can not only stand their ground but also shape the world around them.

The ability to do so is at the end of the day a function of vision, policy objectives, assets small states can leverage, appetite for risk, and the temperament of their leaders. Qatar and the UAE represent two very different approaches that offer lessons but are unlikely to serve as models.

In the final analysis, both Qatar and the UAE may pull off punching far above their weight even if they fail in achieving all their objectives. It comes however at a price paid in part by others that ultimately may come to haunt them.