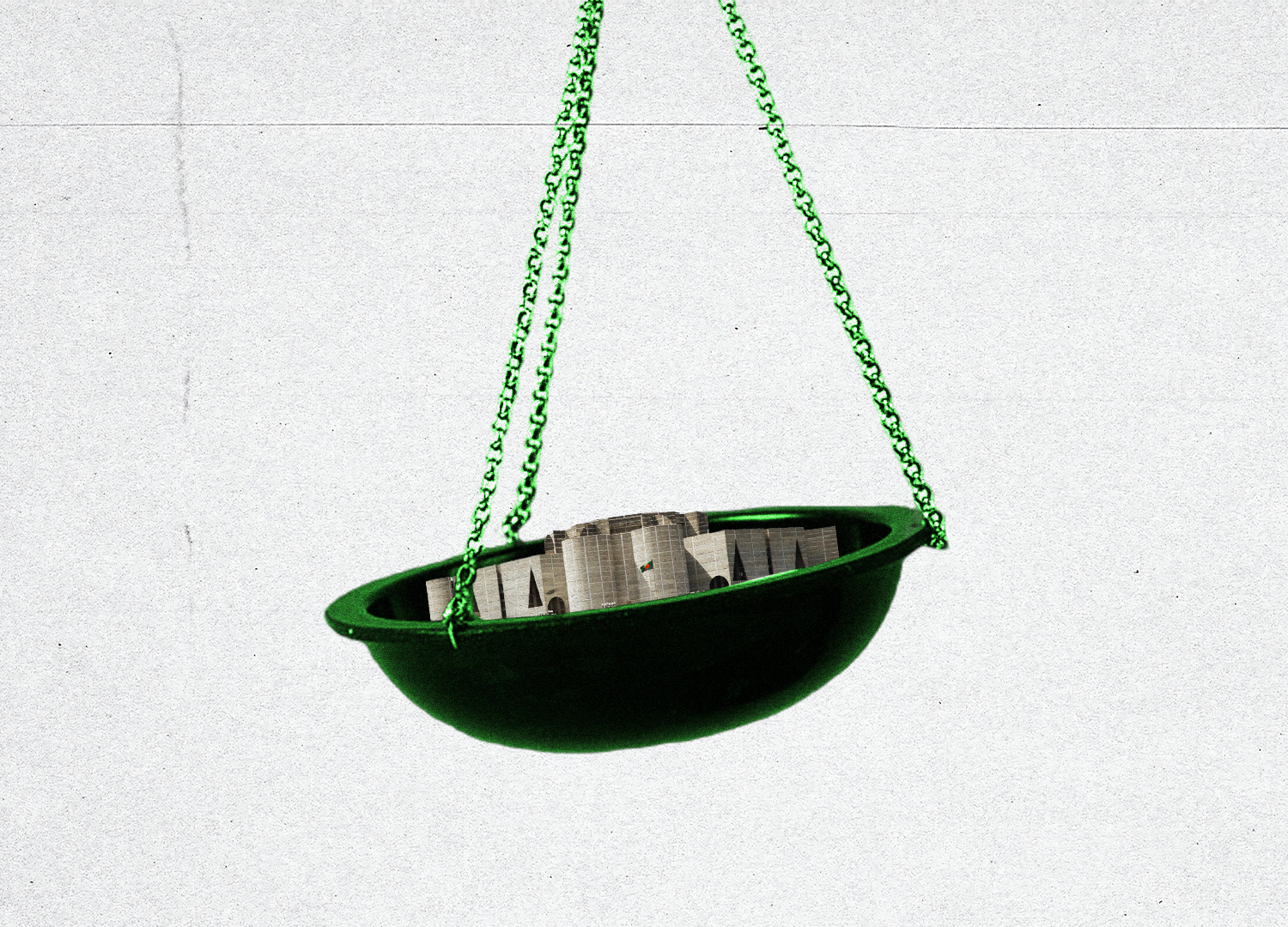

Illustration by Subinoy Mustofi Eron/Netra News

The Monsoon Revolution triggered two monumental shifts in Bangladesh politics. First, on August 5th, Sheikh Hasina was ousted from power, shattering the Awami League’s (AL) long-standing political dynasty and legitimacy. Second, on August 30th, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) formally ended its enduring alliance with Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh (JeI), as BNP General Secretary Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir announced that his party was no longer allied with the political Islamist group.

BNP and JeI have been intermittent political partners since 1991, when democratic elections returned following the fall of yet another dictator, Hussain Muhammad Ershad. That year, the BNP formed a government with JeI’s support, having missed a clear majority. (However, a brief rift arose in 1996 when JeI sided with the Awami League in an election boycott, forcing the BNP government to establish an election-time caretaker regime.)

Yet the BNP–JeI relationship dates back even further.

In 1972, JeI was banned from Bangladesh’s political landscape for supporting Pakistan during the 1971 Liberation War and for its leaders’ involvement with the Shanti Committee and paramilitary forces such as Al-Badr and Al-Shams (collectively known as the Rajakars). JeI was eventually rehabilitated as a political party in 1976, during President Ziaur Rahman’s tenure and the BNP’s first time in power. (BNP officials would argue that this privilege was not exclusive to JeI—they contend the Awami League was also rehabilitated after Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s BAKSAL had absorbed it.)

Since then, JeI’s political influence has steadily grown. In his book God Willing, political scientist Ali Riaz—now head of a constitutional reforms committee—charts how JeI increased its electoral base from around 750,000 votes in 1979 to 1.3 million by 1986. JeI went from winning 10 out of 300 parliamentary seats in 1986 to 18 in the 1991 elections. Those 18 seats were critical for BNP to form a majority government, elevating JeI to the status of kingmaker and solidifying its position as the fourth-largest political party.

After briefly flirting with the Awami League in the 1996 election, JeI returned to the BNP’s side in 2001. The JeI won 17 of the 31 seats that it contested, and the party gained several cabinet positions in the BNP-led government. During the global War on Terror, JeI largely escaped scrutiny despite accusations that it (along with some BNP members) had ties to militant groups, thanks to its seat at the table.

Even after the military-backed caretaker regime took control in 2007—arresting top leaders from both AL and BNP—JeI mostly avoided large-scale purge, maintaining such good relations with the generals that it urged BNP to join elections under the caretaker government, despite Khaleda Zia’s doubts.

JeI’s luck finally ran out after the Awami League took power in 2008 and held it until Hasina’s fall on August 5, 2024. In that 16-year span, JeI activists were persecuted or disappeared, its leaders were arrested and executed under politically motivated war crimes trials, and it was banned from the 2018 and 2024 elections.

But it’s not as if JeI was inactive in the last 16 years of the AL rule.

While the main organisation was under pressure, its student wing, Islamic Chhatra Shibir (or Shibir), went underground on university campuses. It has since resurfaced to dominate student politics. A junior coordinator of the Anti-Discrimination Movement that led protests against Hasina, Shadik Kayem, revealed himself to be a secret Shibir leader. Another key student leader, Sarjis Alam—originally from the Awami League’s student wing—now champions Shibir’s role in the uprising that toppled Hasina.

Anecdotal reports suggest some AL student activists in the past decade were actually Shibir members in disguise. In a Kafkaesque twist, JeI recently held a demonstration calling for the release of a jailed Awami League leader—claiming he had secretly been one of their own. As a result, Shibir’s rapid re-emergence has led to clashes with BNP’s own student wing, Chhatra Dal, which was blindsided by Shibir’s organisational makeover.

Not just the Chhatra Dal, JeI’s rise has evidently rattled the BNP, whose leaders have revived the party’s notorious wartime legacy as collaborators. On January 2, 2025, BNP Senior Joint Secretary General Ruhul Kabir Rizvi publicly asked, “What was your [JeI’s] role in 1971? In which war sector did you fight?”

Such questions, though seemingly rhetorical, are crucial for establishing political legitimacy. The Liberation War occupies a central place in Bangladesh’s collective memory, long dominated by the Awami League’s singular narrative. Now, the BNP is trying to challenge that narrative and use 1971’s legacy to undermine JeI or court disillusioned AL supporters.

Meanwhile, JeI Ameer (chief) Shafiqur Rahman insists that although the formal JeI–BNP alliance is over, their on-the-ground relationship remains cooperative. He calls for unity across party lines against “fascist” forces, championing a “new” Bangladesh in the spirit of the July Revolution. These appeals for unity come with pleas for communal harmony, including Rahman’s claim that Bangladesh is a “unique example” of different faiths living together peacefully—made even as Hindus and Adibashis in the Chittagong Hill Tracts face horror, and ISIS flags have resurfaced among hardcore Islamist processions.

Particularly striking are Rahman’s recent comments on JeI’s wartime past. He defended JeI’s stance on a united Pakistan and shifted blame to India for forcing East Pakistanis into a do-or-die predicament, while also criticising West Pakistani leaders for being heavy-handed. Although he dismissed the 2013 war crimes tribunals under the Awami League as politicised, he voiced support for bringing war criminals to justice. These statements reflect JeI’s long-term strategy to shape the public narrative—fueling anti-India sentiment, framing India as equally culpable for the 1971 genocide, and eventually absolving JeI of its darkest chapters.

For skeptics, Major Shariful Haque Dalim’s interview on January 5 with Elias Hossain—a former journalist turned pro-Jamaat YouTuber—illustrates this approach. Dalim participated in the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Bangladesh’s founding president and Hasina’s father. In the interview, watched live by millions, he suggested India was responsible for the December 14, 1971 scholasticide and minimised the atrocities committed by Pakistani forces and their collaborators.

Although Dalim fought in the Liberation War and received a gallantry award, he justified his role in the Sheikh family massacre—which earned him a death penalty in absentia—by citing Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s pro-India stance. His claims echo JeI’s broader propaganda, which frames the party as one of the “patriotic” forces during 1971, alongside the military, while seeking to downplay its complicity in wartime atrocities.

Reworking public sentiment takes time, and JeI appears in no rush.

While the BNP demanded immediate elections after Hasina’s fall, JeI has remained patient, presumably to strengthen its support base: journalist Tasneem Khalil predicts JeI could emerge as a major conservative force in Bangladeshi politics.

JeI was instrumental in Bangladesh’s formative decades, promoting Islam as a political force. Its absence during the Awami League’s last decade allowed other Islamist groups to flourish. Now, these players may seek alliances with JeI, which has signaled openness to collaborating with parties beyond the BNP to form a broader Islamist coalition. For instance, Islamic Andolon Bangladesh (IAB), another influential Islamist party, has called for unity among similar organisations, including JeI.

If JeI ultimately comes to power, it would be yet another ironic twist in Bangladesh’s political history—one partly enabled by the Awami League itself, which long vilified JeI. AL’s historic missteps—from the blanket pardon of Rajakars in 1973 to its expedient alliances with JeI in the mid-1990s, from failing to hold credible war-crimes trials to Sheikh Hasina’s 15-year authoritarian reign—have paved the way for JeI’s ascendancy in this unfolding game of thrones.

Nafis Hasan is a Bangladeshi writer, researcher, and editor at Jamhoor, a left media platform focusing on South Asia and its diasporas. Learn more at nafishasan.com.

source : netra.news