By John Dayal

Indian women, still deemed politically passive, have taken the lead in shooting down an advisory from the ruling party’s chief ideologue calling couples to have three children to ensure the country does not fall short in the workforce it will need to be among the top economies in the world.

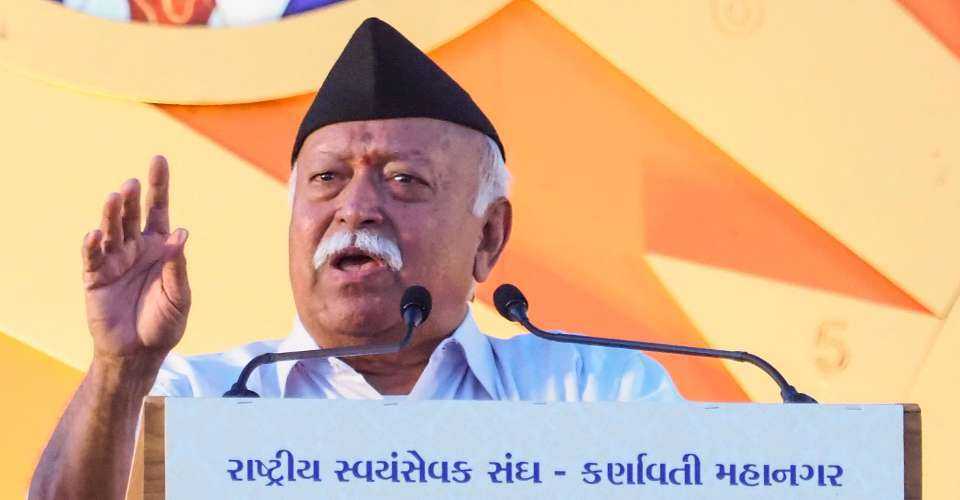

Mohan Bhagwat, supreme leader of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS or National Volunteer Corps), in a recent statement, advocated that couples have three or more children to avoid the problems being faced by developed economies such as Japan, South Korea, China, and several in Europe.

Renuka Chowdhury, a Congress member of parliament retaliated in a talk with the media: “Mr. Bhagwat is saying produce more children. Are we rabbits that we will keep reproducing?”

A 2023 UN study estimated that 20 percent of India’s population will be elderly by the year 2050. By the end of the century the percentage will be around 36 percent, it has been estimated.

The subtext of Bhagwat’s speech however was his group’s fear that Muslims will overtake, and overwhelm, the Hindu community which will cease to be a majority in its birthplace sooner rather than later this century.

Religious demography is serious political and ideological business. The RSS has made huge political capital, and vast sums of money from devout Hindus among the non-resident Indian (NRI) diaspora, claiming they will be swamped and overwhelmed by Christianity and Islam. Venomous slogans have been coined against the followers of these “alien Abrahamic religions.”

While Muslims are presented as pro-Pakistan and terrorists, Christians are said to be secessionists and devouring Indian cultural values. Various political and RSS leaders have been calling for the disenfranchisement of Christians, curbs on Muslims, and exhorting Hindu women to have anything from four to ten children in this “Demographic Great War.”

The RSS is the mother organization of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) which has been in power for a decade. The government has officially not discarded the two-child policy initiated 48 years ago to bring some semblance of control over a galloping population that still promises to take India past 1.60 billion by the middle of this century.

India will hold its next census in 2025. The 2021 decadal census was not held in the lockdown during the Covid pandemic. The government has not explained the delay, especially as it very successfully carried out the general election this year, as well as elections to several large state legislatures.

The 2011 census recorded India’s population at 1.21 billion with Hindus at 79.8 percent, Muslims at 14.2 percent, Christians 2.3 percent, Sikhs 1.7 percent, Buddhists 0.7 percent, Jains 0.4 percent, and other religions and persuasions at 0.7 percent. About 0.2 percent did not disclose their religion.

Like clockwork to time with the national census and elections, the country has seen fears by various Hindu majority groups, their voice magnified a thousand-fold by social media. This demographic battle, “population jihad” as its leaders call it, is being waged by Muslims, the country’s second-largest religious community, which is accused of rampant polygamy and multiple children in the family.

Some Hindu sadhus associated with the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP or World Hindu Council), which shares many leaders with the RSS and the BJP, have been especially vocal. Ahead of the 2014 parliamentary election, then VHP chief Ashok Singhal claimed that the Hindu population was growing at a much slower rate than that of Christians and Muslims.

“Hindus should not restrict themselves to two children per family. Only when they produce five children will the population of Hindus remain stable,” Singhal said.

In fairness to them, it is not just the Hindu religious and political leadership wary of Muslims. Similar sentiments have been voiced by a section of Catholic religious heads in Kerala and indigenous groups in states such as Assam in the country’s northeast region.

Statistical projects do not support this political xenophobia, with even the US-based Pew Foundation saying it will take over 250 years for Muslims to equal the number of Hindus in India.

The decadal growth rate for Indian Muslims decreased from 32.9 percent in 1981-1991 to 24.6 percent in 2001-2011. This decline is more pronounced than that of Hindus, whose growth rate fell from 22.7 percent to 16.8 percent over the same period. In both communities, the decline has been attributed largely to the education of girls.

While the 2011 census data shows that the rate of growth of Muslims in India is higher than that of Hindus, both are, however, above the national average.

The decennial rate of growth of Muslims is indeed decelerating. As far as the Christians are concerned, they are stagnating at a mere 2.3 percent, their growth rate for at least three decades, and may be declining, as in Nagaland, the small state that, with Meghalaya and Mizoram, has a Christian-majority population.

The Pew Foundation showed that Christians have been significantly below the national average while Hindus, and of course Muslims, have been well above that figure.

The population of Sikhs and Buddhists is also proportionately decreasing. Buddhism has been one of the major religions in India for 2,500 years and the current number of its followers in the land of its origin are of civilizational concern.

Historically, the Hindu revivalist movement of the 19th century was the period that saw the demarcation of two separate cultures on a religious basis — Hindus and Muslims. This divide deepened further because of partition in 1947.

Since the 1992 demolition of the Babri mosque in Ayodhya, the division has become institutionalized in the form of a communal ideology, posing a major challenge to the country’s secular social fabric and democratic polity.

Professor Amitabh Kundu, arguably one of India’s most senior statistical social scientists, allays all fears about population projections. Demographic parameters have traditionally been considered stable — unlike socioeconomic indicators, they change only in the long run.

“The narrative of the demographic dragon eating up all the benefits of development due to uncontrolled fertility has, however, changed within a decade into concerns that a labor shortage could decelerate economic growth,” he says.

The replenishment rate for populations to remain the same or increase is just about 2.1 percent. However, India’s top two most populous states, Uttar Pradesh with 2.35 percent and Bihar with 2.98 percent, outpace the other states.

Political leaders and others in the southern part of India have, since Modi’s second coming in 2019, said they see the danger to democracy from the differential birth rates of three major north Indian states, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, and the rest of the country, particularly the southern states.

This threatens to skew the political dynamics of the country as the commission to demarcate new parliamentary constituencies will be working on the 2025 census figures. The northern states will get more seats in proportion, making their share even more than the massive figure they have now. The result will be that in parliament, whether the total seats remain the same or are increased, the southern states may find themselves all but marginalized, their voice muted.

source : uca news