An uptick of an old fault line—-the protracted Bangladeshi discourse over history has recently stepped up since a spokesperson of Dr. Mohammad Yunus’s interim regime announced that the national narrative deserved a more inclusionary trajectory. It is one of the frontline messages since Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s (Hasina) despotic regime suddenly fell when she fled to India to save herself from the surging mobs marching towards her official residence. Hasina’s repressive rule had its roots in her and her party’s unilateral, dynastic, and personalized claims over the nation’s historiography. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s (Mujib) BKSAL stint, the Awami League’s (AL) ascendent leadership and more decisively Hasina’s weaponization of history are the blatant examples of misusing power to reconstruct the historical storyline. Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past: Power and Production of History, 1995 is one of the best post-modern portrayals on the subject. But the past sometimes hits back and vigorously! This is what I implied in my article “Bangladesh at 26: Encountering Bifurcated History and Divided National Identity,” Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, Villanova University, Pennsylvania, Spring 1998. The “manufactured paradigm of history” is now a part of the academic dialogues.

Bangladesh history has been an occupied territory under the exclusionary hold of certain charismatic leaders, their parties and the intellectual allies who imposed politically motivated denials on the country’s previous milestones. The AL’s domination of history began in 1971 when the party held a monopolistic switch over the independence movement launched from Indian soil. While Mujib was in custody and the AL leadership was still in a disarray under the Pakistani military’s bloody crackdown, Tajuddin Ahmad, a resolute Awami Leaguer, took it upon himself to mobilize the remains of his allies and sought Indian help. But the core AL supporters and their student cohorts insisted that Mujib’s name must continue with the independence campaign even though he was absent from the war theatre. The Mujib loyalists designed a splinter group called the Mujib Bahini—a secretive but privileged faction that received armed training under the Indian army’s supervision. So, the discernible Mujibization of Bangladeshi narrative has a prehistory that still hovers in the national pantheon.

The doubts and suspicion about Tajuddin Ahmad’s prominence was more than whispers of his antagonists when after Bangladesh independence, he lost his position as the finance minister. It happened not long after Mujib returned from Pakistan jail. Tajuddin’s daughter Sharmin Ahmad’s recount (Tajuddin Ahmad: Neta O Pita, 2014) of 1971 does not tally with the dedicated Mujib and Hasina admirers. Once freed from Pakistan jail, Mujib took over the total leadership of the party, the governance, and the historical recital. His charismatic pinnacle rose above all other leaders and institutions in the country—his stamp ruled the intellectual establishments as well. Mujibism, an imprecise ideological brew, came as an additional bond to Muijib’s personal command. He had already earned the accolade as the “Bangabandhu” (friend of Bengal). But more tributes came with his daughter’s ascendancy when Mujib was not alive. Hasina’ authoritarian sweep began after the 2008 election victory that only ended in her recent ouster by the furious protestors. Over that long but controversial term in office, it became a punishable offence for anyone to deny (late) Mujib’s status as Jatir Pita, the father of the nation. Textbooks of history and social studies brimmed with Mujib stories; the flourishing hagiographies and the sponsored storylines blended the professed Mujib glories. Except the relentless contest over who first called for independence in March 1971—Ziaur Rahman or Sheikh Mujib, the years from 1975 to 1996, had fewer straight assaults on Bangladesh history.

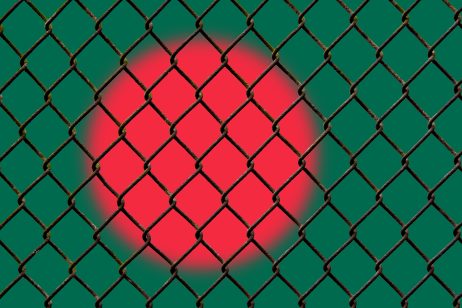

Personalization of Bangladeshi history swelled since Hasina stuck herself in power by rigging three consecutive elections rejected by the major parties and most democratic leaders around the world. After August 5, the day she fled the country, Bangladesh history, decapitated by dynastic overkill and distortions, became the shackles for exiled Hasina, her besieged AL, and the accomplices in jail, hunkered down or on the run. The post-independence Bangladesh demonstrated a not-so-concealed “hero-worship” or an aching for a charismatic leadership—both dramatically bared under Mujib and Hasina respectively The BNP leadership also centered on President Ziaur Rahman and later his widow Begum Khaleda Zia. General H. M. Ershad, once out of power, remained politically influential as a chronic deal maker but did not carry the personal popularity of Mujib or Zia.

Mujib, Hasina, and the AL buried the accomplishments of the earlier Muslim leaders—A.K. Fazlul Huq, H. S. Suhrawardy, Maulana Bhashani and a host of others who stimulated Muslim empowerment in undivided Bengal. Awareness of the past still matters in the present. Their ventures, however, climaxed in Pakistan, a separate Muslim homeland, the outcome of the 1947 controversial partition. The collective memory about 1947, however, seemed nearly forgotten in Bangladesh after the ferocious armed struggle in 1971. And yet, it was from same territorial swath that Bangladesh came out as an independent state—East Pakistan’s institutional experiences are still the undeniable epicenters of Bangladesh’s inheritances today. Still Bangladeshi past became a battle ground of retributions between those who still cherished their Muslim identity and those who believed in a lingo-centric secular nationalism. Muslim nationalism, a patent bequest of the Muslim masses, was different from the AL-supported post-1971 “Chetona.” Such unbending contestations around history divided Bangladesh by the walls of “US against Them” with the country’s stability and security at risk. Authoritarian states display such cult-like postures, which had national disasters that Bangladesh recently watched during Hasina’s iron-fist rule.

Hasina mixed victimhood (from the 1975 violent coup that killed her father and the family members) with her festering revenge! She erected Mujib’s statues at public places— Mujib, his wife and the children killed in the 1975 coup received the state honor and their birthdays were public holidays. The AL accomplices fondly called Mujib the best Bengali in the history of the Bengali speaking people— an unprecedented endorsement in the archives of the Bengali speakers. Occasionally, Hasina boasted in public that it was her father who earned the country’s independence, and she assumed as if she were the rightful inheritor of power in Bangladesh. However, the bulging anger against the Mujib icons, attack on his old residence and the more recent cancellation of public holidays for the 1975 coup victims of Hasina’s family hinted that the ferocity of anti-Hasina anger likewise fell on the Mujib rule in the yore.

History, nevertheless, transports “leader-centric” propensities revolving around the winners, and embracing chauvinism. But flawless history does not happily marry patriotism, as Prasanjit Duara, an outstanding historiographer warned decades ago. Historical accounts are, however, not immune to counter-narratives. Modern and post-modern historians are daring the western and non-western historical assertions at regular intervals. After probing the fundamentals of American constitutional and independence history, Charles Beard lived in exile in Canada! Exclusive faiths, charismatic and dynastic leaders, partisan groups, or patriotic cults do not deserve a total prerogative over history. A new breed of historians no longer dumps M. A. Jinnah with the exclusive “guilt” of the 1947 Partition. The subaltern treatises briskly challenge the elite dominated independence history of India.

A modern state does not need a “father of the nation” to survive as a legal entity in the international community! What is happening in Bangladesh now are the bracing correctives of our prior exclusionary narratives. Hasina’s totalitarian madness was well entrenched, but when it suddenly plummeted before the firestorm of desperate quota protesters, it felt like a surreal dream! The catastrophic events of July-August 2024 indeed jolted the historical imagination in Bangladesh. The end of Hasina’s brutal rule released the energies previously trampled under her merciless hegemony.