RAHUL JAYBHAY

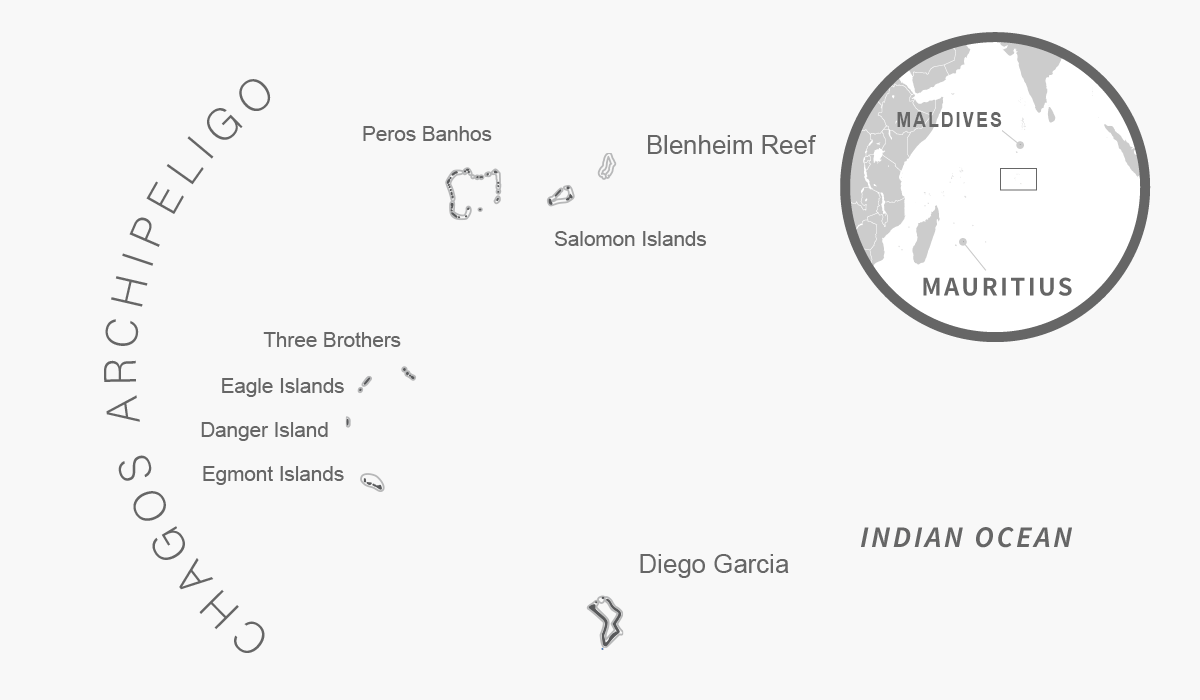

India supported Mauritius sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago. But New Delhi must also be relieved that the United Kingdom, which agreed this month to hand back the disputed Indian Ocean territory, will continue with a lease over Diego Garcia for 99 years. This island, site of a major US military base, gives Washington the latitude to ensure its naval presence in the Indian Ocean region to balance China’s naval footprints.

But India had a different view of Diego Garcia and the US presence in decades gone by.

Scrambling through the official records on Abhilekh Patal, a digital repository maintained by the National Archives of India, and the Prime Ministers Museum Library, I discovered the extent of India’s past aversion to Washington’s role in the Indian Ocean region. The story that emerges is a remarkable insight into the shifting attitudes of the modern era.

In 1966, Britain and the United States inked a deal to fix “defence installations” and “staging post[s]” in the British Indian Ocean Territories of Aldabra, Farquhar, Desroches and the Chagos Archipelago. Controversy erupted when Diego Garcia, a remote island, was installed with a “communication centre”. It created the plausibility of turning the facility into a “base” with additional upgrades such as “airstrips” to accommodate bombers and dredging activities to harbour US nuclear submarines.

Australia’s then prime minister, Gough Whitlam, proposed “Indo-Australian” participation to “urge” both the Soviet Union and the United States to show “mutual restraint” regarding militarising the region.

Indian policymakers opposed such efforts by Washington and London as “hostile” to its strategic interests. The creation of the base also disrupted India’s vision of an “area of peace”. New Delhi was opposed to any foreign bases close to its periphery. Further, Britain also spurned Maldives’ “Gan” facility as their fiscal deficit deepened, exacerbating Indian qualms.

Fearing possible American intervention to fill the British void, a secret memorandum by the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) in December 1974 revealed India’s paranoia that “establishment of any hostile presence so close to Lakshadweep and Minicoy would obviously have serious security implications.”

To squelch the prospects of the “arms race” and proliferation of naval bases, Australia’s then prime minister, Gough Whitlam, proposed “Indo-Australian” participation to “urge” both the Soviet Union and the United States to show “mutual restraint” regarding militarising the region.

But the Australian government hesitated to publicly call out Americans for their actions. India negated Australia’s offer because it excluded “small littorals” and interfered with India’s non-alignment strategy. Instead, New Delhi advocated trimming the pursuit of bases by the United States and reducing the Soviet’s naval presence to stabilise the region.

India’s policy of resisting the militarisation of Indian Ocean became an imperative following the Bangladesh crisis in 1971 when Washington deployed the USS Enterprise and accompanying 7thth fleet in the region. India’s policy remained consistent to oppose such naval postures, which complicated Indian’s approach to the now dismembered Pakistan. While answering queries in Lok Sabha in November 1973, the MEA stated that maritime competition in the region would make it difficult to realise the “area of tranquility [peace]” as envisaged by India and small littoral states.

In June 1975, the US Senate Armed Service Committee speculated about the expansion of Diego Garcia, owing to the fear of the Soviet’s interdiction of oil supplies from the Gulf to Western Europe and Japan. Not only India but non-aligned littoral states also publicly denounced the US decision to militarise the base. A ministerial meeting of the Coordination Bureau of the Non-aligned countries made a declaration to categorically “condemn … the expansion of the installations” at Diego Garcia. Such military expansion violated the 1971 UN General Assembly resolution to steer great powers away from the Indian Ocean region. It nullified the Lusaka Declaration of non-aligned countries in September 1970 that publicly called to “free” IOR from great power competition.

The brunt of India’s criticism was not limited to the United States but also extended to Britain. Parallel to developments in Diego Garcia, Britain was willing to arm the South African government in the mid-1960s and early 1970 and revamp its naval base at Simonstown for “external defence”, mainly to outpace Soviet naval incursions. India’s then High Commissioner to London, Apa B. Pant (1969-1972), opposed Britain’s policy decision as it compromised India’s “area of peace” mandate as a means to dilute great power rivalries that might engulf India.

Today, India’s rhetoric, however, is considerably different as the result of changing international conditions. As bipolarity deepens and China threatens India, New Delhi choses to rely on Washington for continued operations in the Indian Ocean region to check Beijing’s presence. New Delhi is also aware that it cannot solely provide security in the region. Washington’s presence in Diego Garcia maintains the preferred balance of power as India wishes and challenges China’s basing options by undercutting its tendency to dominate the region.

Source : lowyinstitute