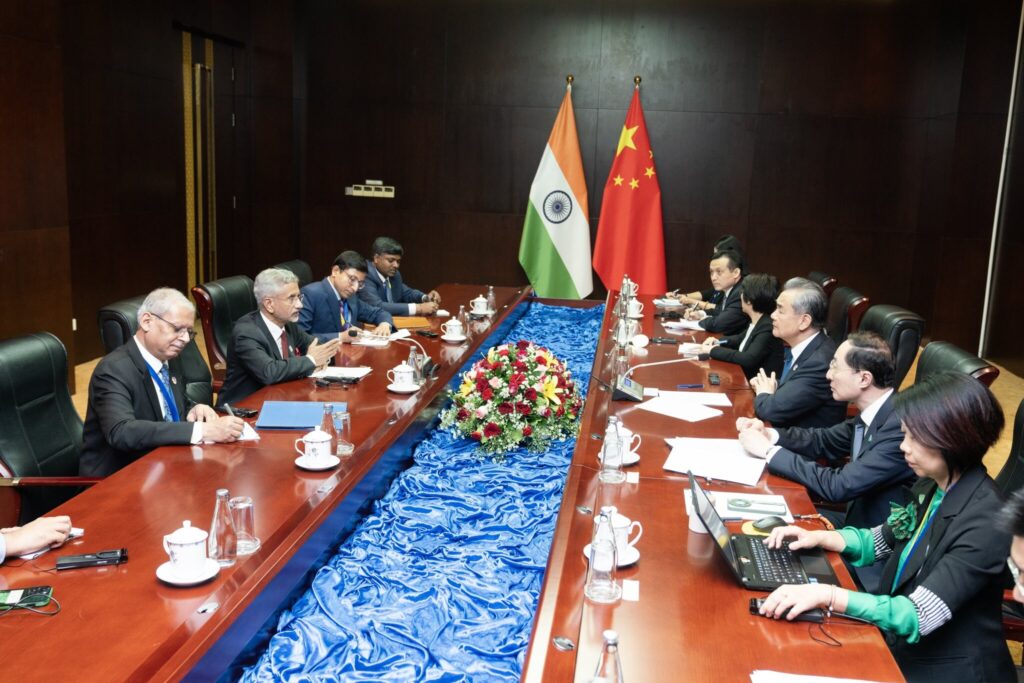

On September 12, India’s National Security Adviser Ajit Doval and China’s top diplomat Wang Yi met on the sidelines of the BRICS summit in St. Petersburg, Russia, to discuss tensions along the disputed India-China border, also called the Line of Actual Control (LAC). The meeting highlighted the stark difference between New Delhi and Beijing in terms of the urgency that they each accord to the resolution of the border dispute. In its official press release, India’s Ministry of External Affairs emphasized the need to achieve complete disengagement between Indian and Chinese troops along the border and establish respect for the LAC. On the other hand, China’s statement avoided any mention of disengagement.

Even with the recent agreement reached between the two sides on disengagement and patrolling along the LAC, the contrast in the Indian and Chinese positions betrays a fundamental difference in what the dispute means for the two neighbors. For China, the lingering dispute is not as serious a threat, and may potentially even be a strategic advantage, because it keeps New Delhi’s military resources engaged on the border and thereby hinders its ability to counter Beijing across the rest of the world. On the other hand, New Delhi views the unsettled border as a strategic vulnerability impacting not only its military stance but also the internal political stability of its frontier territories — in particular, Ladakh. Incessant border tensions and the creation of military buffer zones have already upended the lives and livelihoods of several communities along the border in Ladakh. Recent demands for greater autonomy in Ladakh, led by renowned climate activist Sonam Wangchuk, have also highlighted local grievances with governance issues in the region. In this regard, India should take steps to improve access to basic amenities and the quality of governance in Ladakh. Political stability and economic growth along the border can itself be a deterrent against Chinese incursions.

Ladakh Caught in the Crossfire

Ladakh has long been at the center of the territorial dispute between India and China. In 1834, Ladakh was annexed by the founder of the Sikh Empire, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, into his dominion, which later passed into the hands of the colonial British government in India. Colonial authorities then demarcated the border between Ladakh and Tibet, and this border was later recognized by the post-independence Indian government as the official border between India and China. But the border soon became a point of dispute in the 1950s after New Delhi discovered that Beijing was constructing roads through Aksai Chin, which India considers a part of its territory. This development set off a sequence of events culminating in the war of 1962, during which India had to concede approximately 38,000 square kilometers of territory in Aksai Chin to China. The years that followed saw both countries build up significant strategic infrastructure along the disputed border to improve logistical access for their respective troops and strengthen their positions.

Over the years, the militarization and strategic imperatives emanating from the border dispute have created a sense in Ladakh that local concerns are being sidelined. The conflict with China and the creation of militarized buffer zones has resulted in the displacement of nomadic herders in Ladakh, restricting their access to traditional pasture lands. In the aftermath of the deadly clashes in 2020 between Indian and Chinese troops in Galwan, there was further buildup of military personnel in Ladakh, and more than 50,000 troops remain deployed on either side of the LAC. Indian villagers have reported encounters with Chinese army troops, who they claim have prevented them from grazing their cattle.

These local issues have long been the basis of Ladakh’s political demands for autonomy. In 1995 and 2003 respectively, the Indian government created the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Councils for Leh and Kargil to govern these areas with a measure of autonomy within the erstwhile Indian-administered state of Jammu and Kashmir. Then, in 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi abrogated Article 370 of the Indian Constitution and bifurcated Jammu and Kashmir into two union territories administered directly by New Delhi. One of the new union territories was Ladakh. But this direct federal control only sparked more resentment, and protests have gripped Ladakh this year centered on four primary demands: statehood for Ladakh, its inclusion under the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution (which would give the region greater autonomy), a separate public service commission (which would give it the right to create domicile requirements for the recruitment of its bureaucracy), and two parliamentary seats.

India recognizes the need to assuage these local concerns. In 2022, New Delhi attempted to rectify the lack of development in border villages by announcing the “Vibrant Village Programme” (VVP). The VVP attempts to enhance road connectivity and provide access to basic amenities and services for residents along the border. But it is also an attempt to leverage border communities as strategic assets for information gathering, surveillance, and logistical support in service of India’s border security. Along similar lines, in 2023, New Delhi launched Operation Sadbhavana, which aims to build human resources, skill levels, and basic amenities in remote parts of Ladakh. If New Delhi is to strengthen its strategic position relative to Beijing, it would need to undertake a comprehensive effort to develop villages along the LAC.

India Must Nurture Border Regions

In the aftermath of the 2020 clashes, there are signs that India may need to prepare for a perennially tenuous border with China. Although disengagement proposals have continued to progress — and troops have been withdrawn from four places in eastern Ladakh — it remains to be seen whether the latest disengagement plan would restore the status quo ante that New Delhi desires. Further, unless the level of disengagement is equal on both sides, the risk of further Chinese incursions remains high. China continues to build strategic infrastructure along the LAC in order to strengthen its territorial claims and facilitate the swift movement of troops. For India’s security calculations, this means a more militarized and conflict-prone LAC in its totality, which would demand the reallocation of significant resources from other strategic zones like the Indo-Pacific in order to address threats along the LAC.

In order to counter these developments, India would need to strengthen its defensive capabilities and prioritize the stability and development of Ladakh. Enhanced surveillance capabilities, border patrolling, and rapid response tactics will collectively strengthen India’s position along the LAC. But India should also pay close attention to domestic trends in its border regions instead of relying entirely on military deterrence. In times of conflict, local residents can be critical in helping Indian troops operate in high altitude areas. Local nomadic tribes may be especially useful for their traditional knowledge of the territory. Beijing already recognizes this. In recent years, China has developed infrastructure and civic amenities in its border villages in order to boost its territorial claims and support its military. India has responded to these efforts with programs such as VVP and Operation Sadbhavana, but the success of these programs will depend on whether New Delhi can involve the people of Ladakh in the decisionmaking and implementation processes. In this regard, such schemes should also include suitable mechanisms to heed and address local grievances.

Stability on the LAC and in the border regions is critical to India’s great power aspirations. In order to build its influence and project power, especially in the maritime domain, India would need to collaborate with key Indo-Pacific partners, including Australia and the United States. But the security policy of these partners is founded on the notion that India is a rising power, capable of countering Chinese aggression and maintaining political stability in its own territories. A destabilized Ladakh or losses along the LAC will be deterrents to this vision. New Delhi must therefore take care to balance its competing priorities and build a more effective counter to China along the LAC.

source : southasianvoices