Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexei Overchuk’s recent visit to Pakistan opened new avenues for bilateral cooperation between the two countries. During his trip to Islamabad, Overchuk held meetings with Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, President Asif Ali Zardari, and Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar over trade, regional connectivity, and defense. Overchuk’s visit held particular significance for Islamabad because it publicly conveyed Russia’s support for Pakistan’s membership in the BRICS bloc. Pakistan had formally applied for BRICS membership in August 2023 to benefit from economic ties with members of the bloc.

This declaration of support assumes weight in light of the fact that Russia will be hosting the next BRICS summit, to be held later this month. But for Pakistan to get membership in the coveted bloc, it would need to win the consent of all members, including India. Given tensions between the two countries, New Delhi is likely to oppose Pakistan’s application. However, Pakistan’s entry into the BRICS could be in the interest of both Islamabad and New Delhi.

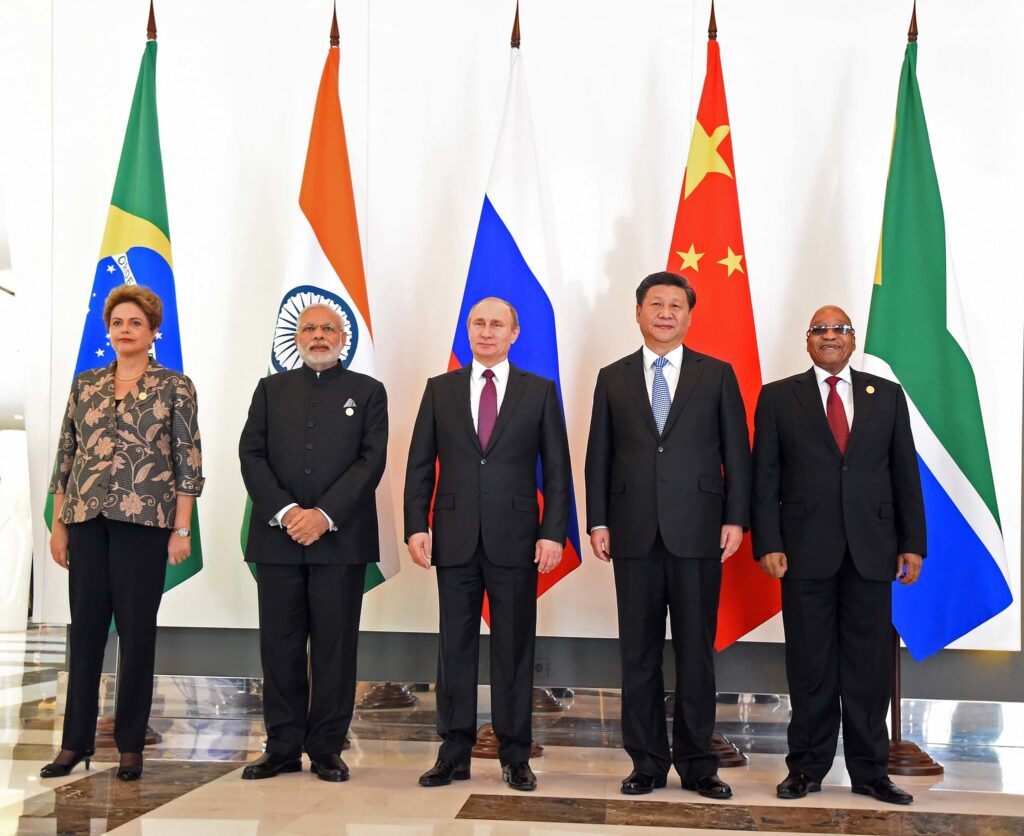

The Rapid Rise of BRICS

Originally composed of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, the BRICS bloc has risen rapidly in both membership and geopolitical significance. Earlier this year, the bloc expanded to include as many as 10 emerging economies, including Iran, Saudi Arabia, and others, and it now accounts for 36 percent of global GDP.

The key thrust of the BRICS bloc is to seek the inclusion of the Global South in what many of its members perceive to be an international order dominated by the West. At last year’s BRICS summit, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa called for reform of the United Nations, and especially the UN Security Council, to make it more inclusive and democratic. Along the same lines, in June this year, the BRICS foreign ministers released a joint statement reaffirming their commitment to “greater and more meaningful participation of developing and least developed countries, especially in Africa, in global decision-making processes.”

In recent years, the BRICS has sought to build connections across the Global South through trade, infrastructure investment, and diplomacy, positioning itself as an alternative to Western consortiums like the G7. In 2015, it established the New Development Bank (NDB) as an agency to fund infrastructure projects across the Global South. Compared to Western-led multilateral banks, such as the World Bank and the IMF, the NDB is still at a nascent stage and enjoys limited reach. But for many emerging economies — and especially those that owe heavy debt to the IMF — the NDB represents an opportunity to reduce their reliance on the West.

The BRICS and the NDB have also become more consequential owing to geopolitical tensions between the West and its strategic rivals. For instance, Russia has engaged more deeply with its fellow BRICS members after its expulsion from the Western-led G8 over the 2014 Crimean conflict and the sanctions that followed its 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Similarly, Iran seeks to build ties with the BRICS in order to counter Western sanctions.

Why Pakistan Wants to Join BRICS

Pakistan’s effort to join the BRICS is driven by its severe and long-running economic challenges. In 2022, Pakistan’s GDP growth rate stood at nearly 5 percent, according to data from the World Bank. This figure shrunk to just over 2 percent in 2023-24. The total debt-to-GDP ratio stood at nearly 75 percent in the last fiscal year compared to just under 74 percent in the previous fiscal year. A long-standing decline in foreign investment flows has added to the country’s woes, largely exacerbated by political instability and falling trust in the rule of law.

Under these circumstances, the BRICS has already emerged as a key partner. In light of its challenges, Pakistan has had trouble in securing adequate support from the IMF, which imposes several conditions for its assistance, including the implementation of fiscal adjustments, privatization, structural reforms, and social security nets. This has often necessitated intervention from BRICS states. For instance, in securing its latest tranche of financial assistance from the IMF, amounting to USD $7 billion, Pakistan was aided by financing from Saudi Arabia, China, and the UAE — all members of the BRICS.

In this context, the NDB could also be a promising opportunity for Pakistan. The NDB lends directly to BRICS members or against their sovereign guarantee, thereby making membership in the BRICS critical. Importantly, unlike the IMF, the NDB does not impose conditions for financial assistance, and no member state can veto the decisions of other members based on its economic size. The NDB also allows countries to borrow in their local currencies — a crucially important feature for Pakistan, given its volatile foreign reserves. In addition, the NDB approves loans in fewer than six months — a significant improvement compared to other multilateral development banks which can take several years to process loans.

On the whole, BRICS membership could potentially bring Pakistan much-needed trade and investment in its struggling sectors, especially energy and food production. BRICS members account for 40 percent of global oil production and 42 percent of global grain production. Stronger trade ties with BRICS members could therefore benefit Pakistan’s economy immensely.

Engaging with India Through BRICS

The next BRICS summit will be hosted by Russia this month. In this context, Overchuk’s public support for Pakistan’s membership is a significant development. Yet, induction of new members into the BRICS requires consensus among its members, which includes India.

In recent years, India has seen tense equations with both China and Pakistan, whom New Delhi sees as a unified strategic threat on its border. In his latest speech at the UN General Assembly, Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar reiterated New Delhi’s objections to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which passes through territory claimed by India in Kashmir.

However, in view of the recent setbacks that India has faced in its neighborhood, where multiple governments that were friendly to New Delhi have fallen, India would stand to gain from any opportunities that might normalize ties with Pakistan. Support for Pakistan’s BRICS membership may go a long way in building trust between the two countries. While this may be a long shot, it is not impossible considering some space for engagement between the two countries seems to be opening up with Jaishankar headed to Islamabad for the SCO summit next week.

Pakistan’s inclusion in the BRICS may also provide a forum for New Delhi to engage with Islamabad in a more productive manner. This may be especially crucial to both countries considering regional cooperation mechanisms under the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) have long been moribund. Multilateral platforms such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the BRICS that are not specific to South Asia and thus less politically sensitive could play a role in easing tensions and normalizing ties. In particular, the presence of mutual partners such as Russia can be a catalyst for engagement in these fora.

India and Pakistan may this benefit from initiating talks with each other on the issue of Pakistan’s inclusion in the BRICS. So far, the two countries have not undertaken any diplomatic discussions on this issue, and in the run up to his upcoming visit to Pakistan, Jaishankar has already ruled out any bilateral dialogue with Islamabad on the sidelines of the SCO summit. Yet, at a time of great geopolitical fissures, India cannot achieve its aspirations of becoming a global power without productive relationships with its neighbors. For Pakistan, cooperation with the BRICS can be an economic lifeline — but it cannot achieve that without normalizing ties with India.

source : southasianvoices