For all the stylistic changes and criticisms of the past, there are more similarities than differences in many aspects of Indian foreign policy. While there is plenty to criticise in India’s previous foreign policy and actions, not much appears to have been learned from these mistakes.

From the very beginning, one of these repeated mistakes is that New Delhi often found itself taking complicated positions that put it at odds with its own interests. Take the Prime Minister’s recent visits to Russia and then Ukraine. In addressing the Russian invasion of Ukraine, India is once again engaging in an unnecessarily intricate dance that is likely to hurt India’s interests by satisfying no side.

First was the state visit to Russia. This was bound to be risky and certain to have bad optics because of Russia’s continuing invasion of a smaller neighbour, whose territory Moscow itself had originally recognised. It is a war Russia is prosecuting with a savagery that is reminiscent of a medieval rampage. The purpose of this extended visit was unclear and it brought few material benefits to India, which would have justified and offset the clear risks of openly embracing Putin at this time.

If Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy was not thrilled about it, he could hardly be blamed considering what Putin and his forces were doing to Ukrainians. Implicitly criticising the killing of children, while standing next to Putin, was unlikely to have satiated Ukraine.

The subsequent, seemingly compensatory visit to Ukraine was never likely to have been satisfactory to any side. It was thus understandable that Zelenskyy was less than thrilled. He welcomed India’s help in resolving the conflict but also pointed to India’s refusal to actually sign the communique of the first ‘Peace Summit’ that Switzerland hosted earlier this year.

Not that this ‘peace’ summit was likely to solve anything, but the point was that India was at once trying to ride two horses by attending the summit but refusing to sign the final document.

Zelenskyy’s subsequent comments did not help, of course, but they suggest that while India may think it is walking the path of high moral certainty, it is not often perceived as such outside the rather large echo chamber of foreign policy ‘debate’ in India.

Strategically ‘stupid’ decisions

The problem is not morality but rather whether India’s self-interest is served by such pretzel-like dexterity. Self-interest requires convincing others, not oneself, and all the verbal dexterity is pointless if the audience is unimpressed.

Hence, the standard for the success of dexterity is not just in convincing ourselves of our own goodness. Sadly, this has often been forgotten when making Indian foreign policy. Indeed, India’s Ukraine policy repeats many of its traditional mistakes.

For example, despite waxing eloquently about colonialism and national sovereignty, India found itself unable to criticise the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. India decided instead, in the person of VK Krishna Menon, to try to talk its way out of the contradiction by criticising the near-simultaneous British-French-Israeli attack on the Suez Canal

It did not help, and by the time India made half-hearted attempts to change its line on the Hungarian invasion, it was much too late.

Another example is the Gulf War in 1991. In the changed global situation after the collapse of the Soviet Union, in dealing with the open and shut case of Iraqi territorial aggression that turned every Middle Eastern country against it, India chose to side with the thuggish dictator of Iraq, Saddam Hussein. A more strategically stupid decision would be difficult to find in the annals of diplomatic history.

India’s relative size and weight mean that it doesn’t suffer much from such foolishness. A weaker power might have suffered more and thus learnt to be more pragmatic. But India was able to avoid any serious damage other than to its reputation. For example, the US came to India’s assistance in 1962 when China attacked, despite American unhappiness with India’s position on Hungary and its general preachiness that somehow always targeted the US and the West far more than the Soviet Union or China.

Don’t rely on others’ mistakes

Will India’s traditional advantages continue to hold? Hopefully, yes. India continues to be a large and reasonably powerful state that matters sufficiently to others to give New Delhi some heft in global consideration. India has never been nor is it today as important as New Delhi thinks it is. Though India is a strong and growing power, nevertheless, India’s position is somewhat more disadvantageous today than in the 1950s or even the 1990s.

Today, for the first time, India faces a territorial threat from a neighbour that is head and shoulders above India in material strength and there is little likelihood India will catch up for decades. This is a new situation that was not true even in the 1950s or 1960s. True, India lost the war with China but this was not the result of a huge disparity in strength between the two but more the consequence of India not paying attention to its circumstances. While no doubt a huge mistake, India today faces a situation that is drastically more dangerous.

Of course, one good thing about India’s mistakes is that Xi appears to be handily winning the ‘who can make more foolish strategic choices’ competition. As with measuring power, making mistakes is also relative: those who make larger mistakes are likely to risk suffering more. China has a larger margin for making such mistakes, but even with that discount, it is being far more foolish than India. Nevertheless, New Delhi shouldn’t count on its adversaries’ mistakes.

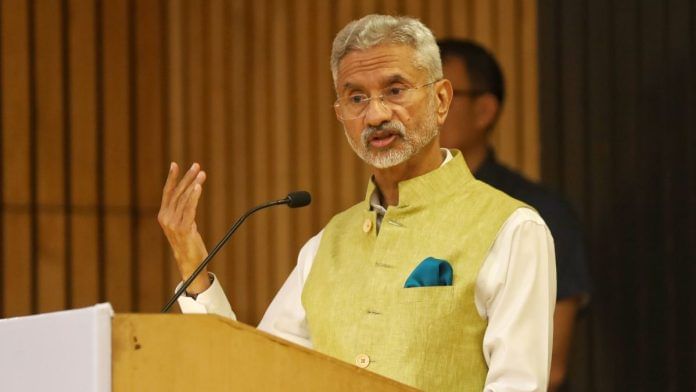

So, EAM S Jaishankar’s recent assessment of US-India relations, where he pushed back on criticisms of the US, was understandable but also surprising.

In the aftermath of the Ukraine visit, but particularly after the coup in Bangladesh, there has been feverish speculation that the US was deliberately undermining India. Such idiotic conspiracy theorising can usually be dismissed: after all, scholarly assessments, using archival evidence, have found little indication of such efforts in the past.

However, the foreign minister’s personal intervention suggests that this ‘debate’ was possibly beginning to have deleterious effects on Indian foreign policy itself. India has less room for the mistakes of the past, and it needs to outgrow them quickly to deal with India’s more troubled and unfavourable circumstances.

Rajesh Rajagopalan is a professor of International Politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. He tweets @RRajagopalanJNU. Views are personal.

source : theprint