By John Dayal :

There is a collective sigh of relief in South Asia’s security, human rights, and economic circles as the 2024 general elections effectively halted Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s arrogant campaign to win over 400 of the 543 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian Parliament.

As the June 4 official counting extends late into the night in the world’s biggest electoral process, Modi, as leader of the single largest party, still expects to be called by the Indian President Draupadi Murmu, to form his record third consecutive government.

However, he will be a much smaller persona than he was when strutting the world stage over the last ten years, embracing US presidents and Arabian kings and lording over smaller countries in the neighborhood.

At the time of going to press, TV counters gave Modi’s National Democratic Alliance 294 seats and 228 to the main opposition, I.N.D.I.A.

An absolute victory of the magnitude he sought, many Indians feared, would have empowered Modi to carry out the political dream of his parent Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), to amend the liberal democratic Indian Constitution, and lay the foundations of a far-right Hindu Rashtra (nation) in which religious minorities were disenfranchised, and indigenous people had no rights over their natural resources.

Modi was stopped in his tracks by a resurgent Indian National Congress, which welded a last-minute coalition of south Indian Dravida parties such as the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam that governs Tamil Nadu, the Marathas of western Maharashtra state, and north Indian parties representing backward classes and Dalits. The coalition was called I.N.D.I.A, the punctuation associating it with the essence of the country, but the name did not run foul of official trademark rules.

At its head was the young Congress leader, Rahul Gandhi, son of the assassinated former premier Rajiv Gandhi, and scion of Jawaharlal Nehru-Indira Gandhi political heritage.

His two-year campaign consisted of long marches across India in which he challenged Modi in every village and town, calling out the prime minister’s crony capitalists, his contempt of the constitution and the rule of law, and his disregard for civil liberties and human rights. India has the world’s largest number of political prisoners and others in its jails, a large number of them Muslims and Dalits.

The I.N.D.I.A campaign clicked, assisted in no small measure by civil society endeavors and an army of social media influencers to reach out in every nook and cranny where even Modi’s mainstream media could not be present.

Gandhi won the two seats he contested, one from Wayanad in Kerala and the other, Raebareli, from the heartland Uttar Pradesh, where he had been defeated last time.

The Congress, which many commentators had given up as a living corpse, has seemingly revived itself in unlikely places, improving its national vote percentage. So have the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and regional parties such as the Samajwadi Party in Uttar Pradesh and the Telugu Desam in Telangana.

Current speculations do not project Gandhi as a probable candidate for the prime minister’s job. Modi has also won his seat in the Varanasi constituency, which covers the Hindu holy city known by the same name in Uttar Pradesh state.

Modi was eventually rejected in his favorite Uttar Pradesh, where the party strength dwindled to half of the possible 80.

Although Uttar Pradesh, the largest state in India, has seen the maximum persecution of Muslims and Christians under BJP rule, a reduction of the party’s strength will not immediately help religious minorities and vulnerable sections.

The BJP has absolute control over the main central Indian states of Madhya Pradesh, Orissa and Chhattisgarh, which are home to a pretty large number of Christians, and Gujarat and Bihar which have sizable Muslim populations.

Modi has also failed to make a dent in Bengal in the west and Karnataka and Tamil Nadu in the south. His allies in Maharashtra have been cut to size by a state coalition of Sharad Pawar’s Nationalist Congress Party and the Hindu ethos Shiv Sena of former chief minister Uddhav Thackeray.

In Kerala, where the BJP tried to get a foothold for over half a century, the party has certainly improved its vote tally, as it has done across the country. Its film actor candidate Suresh Gopi won in the Trissur constituency, making it the Hindu party’s first parliamentary seat in the state.

It is believed that his victory was helped by elements of the various church groups in this traditional stronghold of the religion.

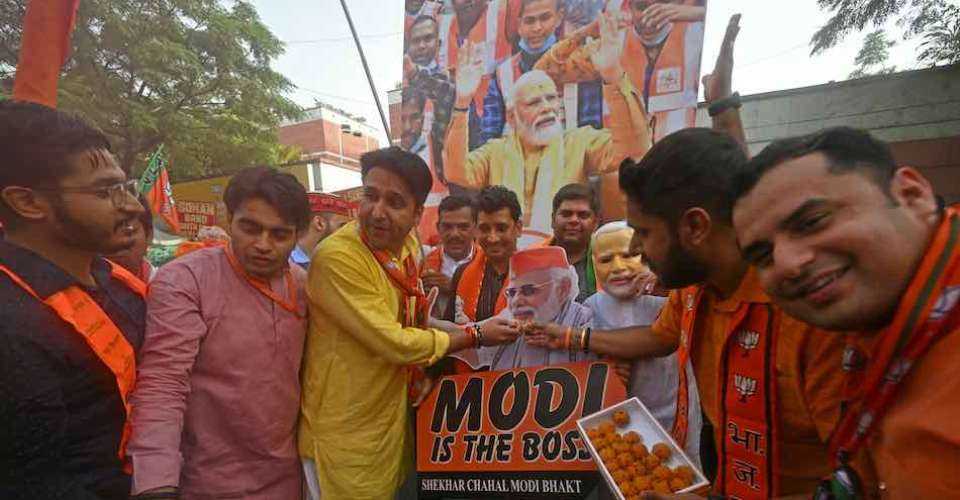

Modi may not give up his dreams so easily. He had already taken several bold steps in the ten years of his rule, encouraging his acolytes, or bhakts, to call him the Hindu Hriday Samrat, the Emperor of the Hearts of the Hindus.

When he was not dressed in the attire and headdresses of the Indian feudal nobility or the armed forces, his favorite dress was of a “sadhu” or a devotee. His massive entourage of cameramen and reporters accompanied him as he meditated in a Himalayan cage, jungles of the foothills, the depths of the Arabian Sea off the coast of his native Gujarat, and lastly at Vivekananda Rock, the extreme tip of the Deccan plateau.

In recent interviews, Modi hinted that he believed he had a divine destiny and was possibly of divine birth. He was dead serious in the interview.

His campaign was earthy. Rahul Gandhi and his mother, Sonia Gandhi, were the primary targets. And Islamophobia was its chief arsenal. He targeted Muslims as vermin and infiltrators conspiring to rob Hindus of their resources, their women, and finally, their place as the majority community.

India’s predominantly Hindu voters — eighty percent of the massive 850 million entitled to exercise their franchise, were not impressed. A two-thirds majority in the two houses, Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha — the two chambers of the Indian Parliament — remains distant, and with it goes away his hopes of altering the statues of its crucial feature of secularism, the state equidistant from all religions, and socialism with its preferential option for the poor.

Modi also faces no threat to his absolute control of the party. He will be 75 in a year, a retirement age he set for his seniors when he took control of the party and became prime minister in 2014. He sent packing his mentor and former deputy prime minister Lal Krishan Advani, who launched the Hindutva campaign in 1990 and eventually got Modi to the prime minister’s house.

The opposition Indian National Congress party hurriedly hobbled together a loose alliance, I.N.D.I.A., with strong regional groups, and had its first-time success with the electorate. The Trinamool Congress, which rules in West Bengal, is not part of this alliance but opposes Modi’s BJP. It successfully protected its turf. Congress also did well in Punjab. The Aam Aadmi Party was a net loser in Punjab and Delhi.

Over the last ten years, the biggest damage has been suffered by the Indian National Congress party, which crashed from 206 seats in the 2009 elections to 44 seats in 2014 and 52 seats in the 2019 elections. On the other hand, the biggest winner has been the BJP, which went from 116 seats in the 2009 elections to 282 in 2014 and 303 seats in the 2019 elections.

International columnist Javed Naqvi noted that in electoral terms, over the last ten years, the BJP has successfully dismantled many state governments that were led by opposition parties. Often, the BJP enticed opposition Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) to resign from the opposition and join their ranks.

Once the governments were dismantled, the BJP used the new MLAs to form its own governments. Examples of this practice can be seen in Goa in 2019 and 2022, Karnataka in 2019, Madhya Pradesh in 2020, Maharashtra in 2022, and most recently in Himachal Pradesh in 2024.

Human rights groups have noted that violence against religious minorities increased drastically from 2014 onwards. The BJP is a political party but RSS is its mother organization. The latter has hundreds of smaller organizations under its wing, including the student group Akhil Bhartiya Vidhyarthi Parishad (ABVP), the farmer’s association Bhartiya Kisan Sangh (BKS), and women’s union Rashtriya Sevika Samiti.

These all call themselves ‘cultural organizations’ with membership running into millions, all of whom are Hindus wanting India to be a purely Hindu country. Vigilantes from these organizations have wreaked havoc on religious minorities, with cases of Muslims being lynched regularly appearing on social media.

In the period 2014-2019 alone (i.e., during Prime Minister Modi’s first term), there was a 500 percent increase in hate speeches by politicians inciting hatred against non-Hindus based on religion. Correspondingly, from 2014-2022, there were at least 878 cases of hate speech and hate crimes against religious minorities in India.

Internationally, despite Modi’s high global visibility and India’s aggressive international public relations, the country does not have easy relations with any of its neighbors, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal, and with China, its main adversary with whom it has had repeated border clashes and which it sees as its main political, geo-strategic and economic competitor.

source : uca news