BY SAIRA BANO

BY SAIRA BANO

Democracy in South Asia is experiencing a troubling decline. Indicators point towards a consistent backsliding. Recent unfair elections held in Bangladesh, Pakistan and Maldives as well as the upcoming election in India against a backdrop of polarisation, highlight the ongoing erosion of democratic values in the region.

In Bangladesh, the 7 January election this year resulted in Sheikh Hasina, the leader of the Awami League, securing her fourth consecutive five-year term as prime minister. The campaign was marred by controversy and a boycott (again) by the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party – a decision that stemmed from the Awami League’s refusal to establish a caretaker government to oversee the election process. Described widely as a “sham” election, the campaign unfolded against a backdrop of violent protests and government crackdowns, contributing to a notably low voter turnout. These circumstances have heightened concerns about Bangladesh’s trajectory towards authoritarianism, casting doubts on the integrity and inclusivity of the electoral process.

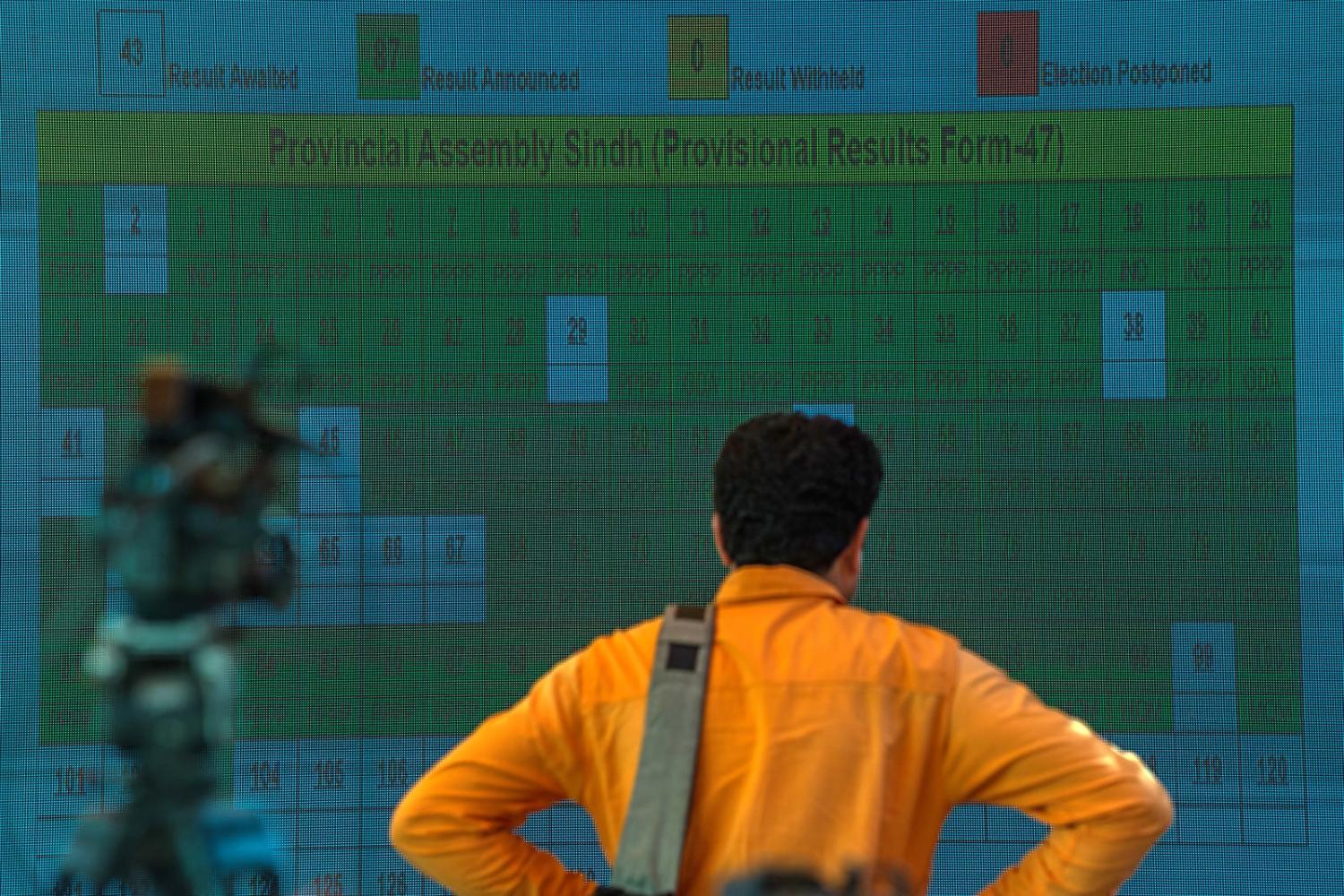

In Pakistan, the election held on 8 February was marred by allegations of irregularities and a lack of fairness, particularly with regard to the treatment of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) political party. The military’s influence remained significant, effectively orchestrating various aspects of the political process. During the election, the military appeared to favour former prime minister Nawaz Sharif, who had recently returned from a four-year exile in London. The military made concerted efforts to stop another former prime minister, Imran Khan and his PTI party, from returning to power after Khan’s removal through a vote of no confidence in April 2022.

Imran Khan himself was sentenced to decades in prison in three separate cases in the week preceding the election. The charges against him ranged from leaking state secrets to engaging in unlawful marriage. The PTI faced significant crackdowns, which included stripping the party of its political symbol, the cricket bat, by the Supreme Court. Many PTI leaders were either arrested or coerced into leaving the party.

Even in the face of such formidable challenges, candidates backed by the PTI successfully secured a plurality of parliamentary seats, winning 93 out of 266, largely attributed to their adept use of social media platforms to mobilise their voter base. However, Nawaz Sharif’s party formed a government through coalition arrangements with other parties, with Sharif’s brother Shehbaz Sharif assuming the position of prime minister for the second time on 3 March. It is evident that Imran Khan’s party will persist in challenging the newly formed government, alleging that it has usurped their mandate. This situation could exacerbate Pakistan’s political instability and compound its economic challenges. The classification last year by the Economist Intelligence Unit of Pakistan as an authoritarian regime underscores the persistent concerns about the violations of democratic norms observed in this election.

Maldives hasn’t suffered nearly the same political strife and in September last year held its fourth multi-party presidential election, resulting in the triumph of opposition leader Mohamed Muizzu. The previous president, Ibrahim Solih, lost following a split in his party close to the election with a resulting division of votes. Although the election was relatively competitive and peaceful, independent observers accused the government of using state resources to sway the electoral outcome and of incentivising the media with financial rewards in exchange for favourable coverage. Allegations of widespread vote-buying were also prevalent during this period, undermining the equity and fairness of the election.

Finally, India is gearing up for one of the world’s largest democratic exercises as it prepares to elect a new parliament in April and May. India’s fervent political environment is characterised by growing polarisation, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi a focal point for criticism over accusations that he adopts strongman tactics and advocates divisive policies. The government has launched an unprecedented attack on civil liberties, free media and minority rights, while also introducing discriminatory laws. Under this administration, India has been downgraded in the annual Freedom House index from a “free democracy” to a “partially free democracy”.

Such region-wide challenges to democratic principles pose obstacles to economic and social development. They exacerbate insecurity and impede collective state efforts to confront urgent problems including extreme poverty and climate change. South Asia represents almost a third of the global population living in extreme poverty, while environmental phenomena, from floods to droughts, have become more prevalent. Political instability resulting from democratic backsliding makes these challenges all the harder.

SOURCE : lowyinstitute