Recently, an “India Out” campaign has been heating up in Bangladesh. On social media, the “India Out” campaign mainly calls on Bangladeshis to boycott Indian products and oppose India’s interference in Bangladesh’s internal affairs, similar to the “India Out” campaign in the Maldives. Together, these two campaigns express the strong antipathy India’s neighbors feel toward India. Meanwhile, the news of a possible visit of Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to China also drew Indian attention.

Against this backdrop, Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar said on Tuesday that there are problems in every neighborhood, but ultimately “neighbors need each other.” “History and geography are very powerful forces. There is no escape from that,” he added. This seems to imply that the Maldives and Bangladesh are historically and geographically inextricably linked to India, so the current “anti-India sentiment” is “not going to create a big disturbance.”

Ironically, however, in his recent book Why Bharat Matters, Jaishankar writes extensively about the Narendra Modi government’s “Neighborhood First” policy. He argues that it has been hugely effective because it pursues reciprocity and generosity toward its neighbors, and at its core, it is a way of making India’s neighbors realize the benefits of maintaining close ties with India. However, the rise of the “India Out” campaigns has made such claims somewhat awkward.

In neighboring countries of India, there is a widespread sentiment of fear, hostility, and opposition toward India. This sentiment has deep historical roots, and the recent outbreak of anti-India sentiment expresses a sense of resentment and opposition toward India’s strong interference in the internal affairs and diplomacy of neighboring countries in recent years. Under the ” Neighborhood First” policy of the Modi government, India has become more deeply involved in the internal affairs and diplomacy of neighboring countries, cultivating support for pro-India forces by manipulating different political parties and religious groups, and suppressing nationalist forces within these countries. Furthermore, India has constructed an illusory narrative of “Akhand Bharat,” which includes almost all neighboring countries within “Akhand Bharat” domain, not only belittling and diminishing other countries but also exposing India’s pursuit of regional dominance.

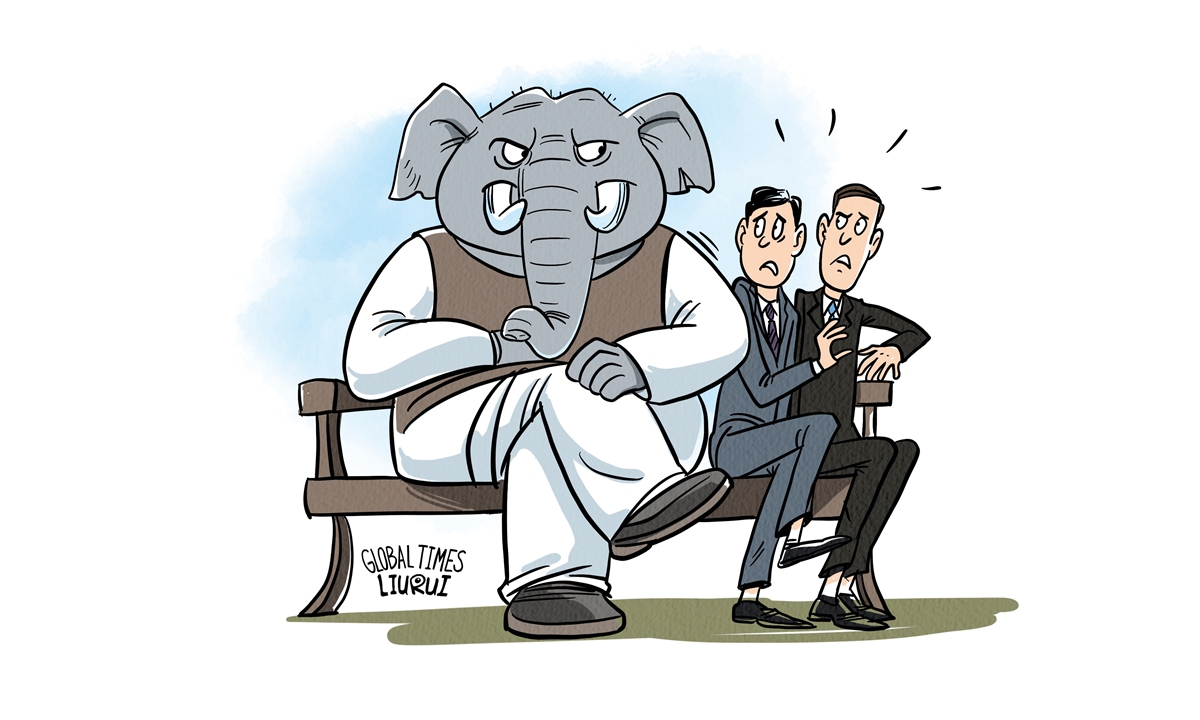

Fundamentally, foreign actions are determined by an ideological consciousness. In this mindset, India’s political elites view South Asia as their backyard and the Indian Ocean as India’s own ocean. India perceives the order in the South Asian region through hierarchical caste-based thinking, considering itself the “Brahmin” at the top of this regional structure, expecting other countries to accept and obey the privileged rule and political guidance of the Brahmins. However, with the withdrawal of the British Empire from South Asia after World War II, South Asian countries have gradually developed into modern nation-states, and the concept of sovereign equality has become deeply ingrained. No country is willing to accept being under India’s influence, and no political elite of any neighboring country is willing to submit to New Delhi. As President Mohamed Muizzu of the Maldives said, “We are not in the backyard of any particular country. The Indian Ocean “does not belong to any particular country.”

Although India does not have the same strength and geographical conditions as the US, it wants to pursue a regional “Monroe Doctrine” like the US did. India’s manipulation of Bhutan far exceeds the US’ control of its backyard country, Panama. In pursuit of regional hegemony, India’s successive leaders have followed two principles: not allowing any major country to cross the Himalayas and not sharing the Indian Ocean with any major country. It treats any major country that does not recognize India’s dominant position in South Asia and the Indian Ocean, as hostile forces endangering India’s interests. In the past, the US was a “hostile force” that endangered India’s regional hegemony. However, with the rise of China, India sees China as its biggest challenge and believes that it is precisely because of China’s “backing” that South Asian countries dare to challenge India.

In fact, it is not China that is undermining India’s regional hegemony, but India’s own policies and thinking. Indian scholar Raja Mohan said something realistic and fair: The idea that India, like the Raj, could keep the Subcontinent as an exclusive sphere of influence was an illusion. At the same time, he pointed out, “it can’t stop the world’s second-largest economic and military power from being a powerful actor in the region.”

In its peripheral diplomacy, India feels physically and mentally “worn out.” The core reason is that it sees itself as the sole hegemon in the region, putting too much of a “burden” on itself. Only by relaxing its mentality, no longer trying to treat South Asia and the Indian Ocean as its own sphere of influence, and working hard to build a multipolar South Asia with other countries, can India truly solve the predicament it faces in its peripheral diplomacy.

The author is professor with the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn