Transparency will help foster trust, which can lead to a

common river management framework for the benefit of all.

During a summer break, The Interpreter will feature selected articles each day from throughout the past year. Normal publishing will resume 15 January, 2024. This article first appeared on 11 April, 2023.

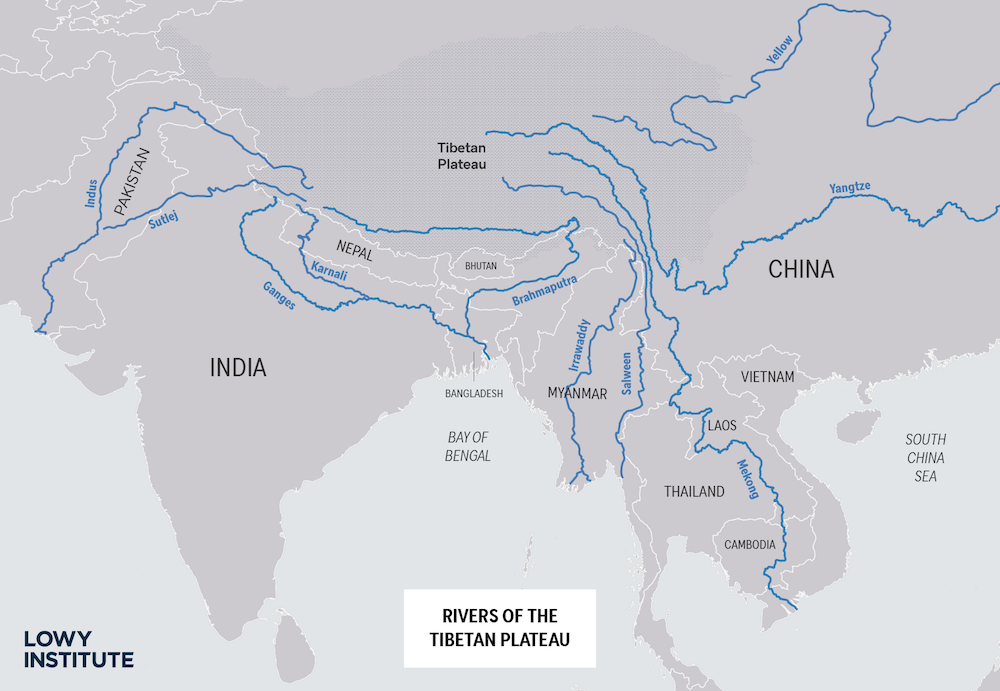

In South Asia, one of the world’s most dynamic regions and home to nearly 1.8 billion people, great rivers are the cultural and socio-economic backbone. Fed by glacial melt and annual precipitation, South Asia’s aqua stalwarts – the Ganges, Indus, and Brahmaputra – have contributed to the rise and prosperity of some of history’s earliest civilisations.

Today, the region’s rivers remain the source of livelihood for millions and are also key to economic growth, food and energy security, and sustainable development. Yet as a recent United Nations report notes, the world is facing an imminent water crisis. By 2030, water demand is expected to outstrip the supply of freshwater by 40 per cent.

In recent decades, South Asian rivers have come under considerable pressure from various factors including industrialisation, urbanisation, rapid population growth, and pollution. As the region remains one of the world’s most impoverished, each country seeks to maximise its use of (shared) rivers to achieve national and international development goals as well as ensure water security.

South Asia’s water woes are exacerbated by climate change, causing erratic extreme weather events (such as droughts) and shifting monsoon patterns, making the region highly susceptible to floods, droughts and disasters. These challenges are compounded by limited institutional cooperation and poor domestic water management, which has resulted in a “tragedy of the commons” scenario, with competition supplanting regional cooperation.

As a result, it becomes more challenging for governments to make informed, long-term decisions concerning the planning, management and development of transnational river basins. This in turn fuels fears over the implications of increased water scarcity and raises concerns over the potential for future water-related inter and intra-state conflicts.

Water management is undoubtedly a complex issue interlinked with other significant challenges, including energy and food security, agricultural production and livelihoods, and state rivalries, not to mention territorial and border disputes. The notable absence of cooperation at a regional level combined with limited bilateral agreements means navigating climate change-induced impacts and other issues such as increased water demand will become increasingly difficult.

Despite simmering regional tensions and the flaring up of bilateral tensions amid global and regional geopolitical challenges, shared water security concerns offer a chance for riparian countries to seek cooperation over conflict.

While neither basin-wide treaties nor river basin organisations may appear likely at this stage, there are measures that countries can undertake at various levels to improve this situation, simultaneously reducing rising geopolitical tensions.

First, all countries should make information on mega hydro-engineering infrastructure plans on transnational rivers publicly available in the languages of the other river basin countries. For India and China, in particular, doing so can reduce fears of “dam-building agendas” and intentions to control transnational rivers. To support these efforts, countries can invite stakeholders, including indigenous people and marginalised groups, to inspect the planned sites of hydro-infrastructure projects.

Second, countries could build on existing bilateral agreements to provide each other with real-time year-round hydrological data as part of greater efforts for basin-wide cooperation. Given China’s past refusal to share data, transparency and a willingness to consistently provide hydrological data, from China in particular, would serve multiple purposes. Aside from reducing concerns about impacts of natural disasters and supporting the planning and management of shared river resources in the downstream region, it could also alleviate suspicion over the downstream region’s fears of Chinese and Indian water manipulation.

Third, basin-wide recommendations should also be considered. Despite the lack of basin-wide institutionalised cooperation along with China’s mistrust of basin-wide multilateral organisations, China could lead by establishing research initiatives with think tanks, scientists, researchers and their counterparts in the downstream countries to discuss scientific, environmental and technical concerns. Doing so could create a basin-wide platform to discuss shared water challenges and solutions. For downstream countries, this presents opportunities to speak up about concerns and encourage further collaboration such as multilateral dialogues, potentially paving the way to create a common river management framework to benefit all countries.

Fourth, countries can follow the example of Bhutan and India by considering joint projects or other forms of collaboration. Given carbon neutrality aims, hydropower collaboration and cross-border electricity trade and exportation could be discussed as part of broader efforts to work together in “good faith” to reduce geopolitical tensions. Pakistan, for example, has suggested water resource management and climate change as potential areas of collaboration within the scope of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor.

For countries whose trilateral or bilateral relations are more complex or linked to unresolved borders, such as in the case of India-Pakistan relations, international cooperation may help reduce tensions while also supporting local efforts to obtain long-term, sustainable and equitable water management practices.

The stark reality of increasing water demand means that all riparian states must prioritise cooperation over competition and conflict on water management and related challenges, or risk (greater) political and socio-economic instability, brought on by a scramble for access to and control of water. Although considerable efforts should be made by China, the upstream country and Asia’s “hydro-hegemon”, it should be noted that the other riparian countries have the responsibility to respond positively to overtures and support bilateral, trilateral and basin-wide collaboration opportunities.