Sheikh Hasina floats into the reception room of her official residence swathed in a luxurious silk sari, the personification of iron fist in velvet glove. At 76 years old and silver-haired, Bangladesh’s Prime Minister is a political phenomenon who has guided the rise of this nation of 170 million from rustic jute producer into the Asia-Pacific’s fastest-expanding economy over the past decade.

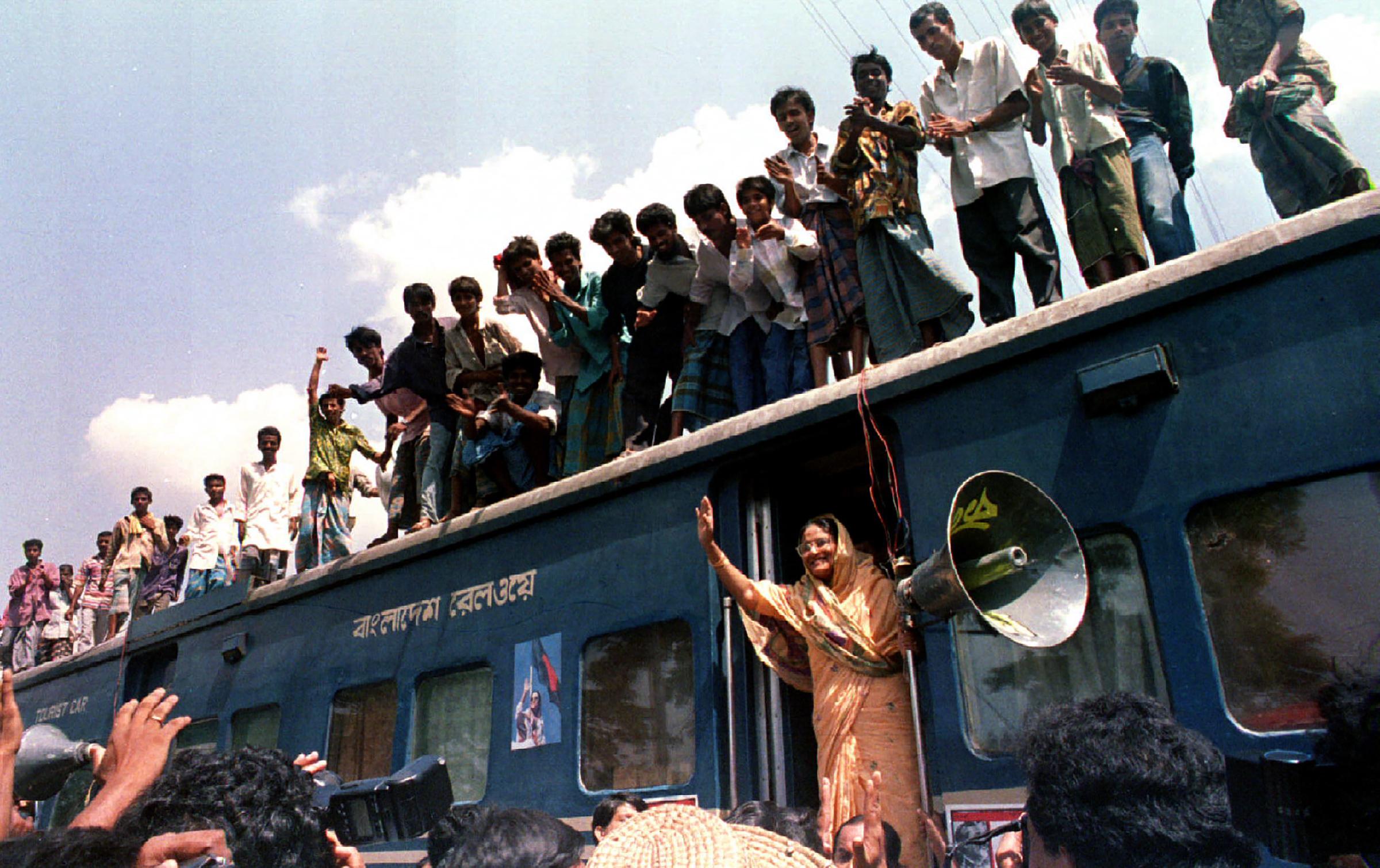

In office since 2009, after an earlier term from 1996 to 2001, she is the world’s longest-serving female head of government and credited with subduing both resurgent Islamists and a once meddlesome military. Having already won more elections than Margaret Thatcher or Indira Gandhi, Hasina is determined to extend that run at the ballot box in January. “I am confident that my people are with me,” she says in an interview with TIME in September. “They’re my main strength.”

Read More: 5 Takeaways from TIME’s Interview with Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina

Few rebuttals are as stark as the 19 assassination attempts that Hasina has weathered over the years. In recent months, supporters of the main opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) have clashed with security forces, leading to hundreds of arrests, police vehicles and public buses set ablaze, and several people killed. The BNP has vowed to boycott the election as they did in both 2014 and 2018 unless Hasina hands power to a caretaker government to shepherd elections. (Their request has historical precedent but is no longer required following a constitutional amendment.)

Bangladesh has taken an authoritarian turn under Hasina’s Awami League party. The last two elections were condemned by the U.S., E.U. and others for significant irregularities, including stuffed ballot boxes and thousands of phantom voters. (She won 84% and 82% of the vote, respectively.) Today, Khaleda Zia, two-time former Premier and BNP leader, sits gravely ill under house arrest on dubious corruption charges. Meanwhile, BNP workers have been hit by a staggering 4 million legal cases, while independent journalists and civil society also complain of vindictive harassment. Critics say January’s vote is tantamount to a coronation and Hasina to a dictator.

“The ruling party is controlling all the state machinery, whether it’s the law enforcement agencies or the judiciary,” says BNP Secretary-General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir, who has been charged in 93 cases—including vandalism and murder—and imprisoned nine times. “Whenever we raise our voices, they oppress us.”

Bangladesh matters. It is the largest single contributor to U.N. peacekeepers and regularly joins exercises with the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. Its vibrant diaspora is intrinsic to business and artistic communities across Asia, Europe, and the Americas. The U.S. is the biggest source of foreign direct investment and the top destination for Bangladeshi exports. And as one of the few developing world leaders to (albeit belatedly) condemn Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Hasina has proven herself useful for the West, not least for taking in some 1 million Rohingya refugees from neighboring Myanmar.

But Washington is concerned about Bangladesh’s drift toward despotism. Hasina was not invited to the latest two U.S.-hosted Summit for Democracy gatherings, and in May the country unveiled visa restrictions on any Bangladeshi undermining elections. In response, Hasina told parliament the U.S. was “trying to eliminate democracy” by engineering her ouster. Asked about her allegation, U.S. Ambassador to Bangladesh Peter D. Haas insists Washington is “scrupulous about not picking sides.”

What a fourth straight term for Hasina would mean for Bangladesh is a polarizing question. Most Americans know the country only from labels sewn into their tees and pants, but it’s a crucible that mixes a Muslim population bigger than any Middle Eastern nation with a significant minority of some 10% Hindus, Buddhists, Christians, and others. Although constitutionally secular, a military dictator in 1988 made Islam the state religion, creating a paradox that has proved fertile ground for radical fundamentalists.

Bangladesh also sits at the front line of the climate crisis. The nation formerly known as East Pakistan may have been forged in the crackle and smoke of a 1971 civil war, but it is water that has dictated life here for millennia. From inland, snowmelt from the towering Himalayas funnels a mind-boggling 165 trillion gallons through Bangladesh’s rivers each year. From the skies, regular cyclones batter a low-lying delta that is 80% floodplain, causing some $1 billion of damage annually. And increasingly, rising seas levels threaten the lives and livelihoods of a population over four times the size of California, crammed into a territory smaller than Illinois. Hasina has championed demands for developed countries to provide their developing peers $100 billion annually until 2025 for climate resilience, a pledge so far unfulfilled. “We don’t want to only receive promises,” she says. “Developed countries should come forward.”

Both these dynastic matriarchs draw legitimacy from their family’s role in Bangladesh’s liberation struggle while minimizing the other’s. Hasina derides the BNP as a “terrorist party,” which “never believed in democracy,” stressing its creation by a former junta. “Khalid Zia ruled like a military dictator,” she says with undisguised venom. Hasina highlights the violence BNP supporters have caused in arson attacks following the disputed 2018 election. The BNP, by contrast, points to the systemic repression of their party and trumped-up charges against its leadership. In truth, bloodletting is sadly common on all sides. “Bangladeshi politics has often included street violence,” says Meenakshi Ganguly, Asia deputy director for Human Rights Watch. “That is true for all major political parties.”

But much can change over four decades and today Bangladesh’s opposition complains of being unable to campaign on the street or express themselves in the media without fear of arrest, assault, or legal challenge. “It’s not just the day of elections that matters for free and fair elections,” says Ambassador Haas. “It is the entire process and environment leading up to it.”

The burning issue for Hasina is that were she removed from power she would likely encounter the same kind of repressive retribution that her government is currently inflicting. “The Awami League are all so scared,” says Zillur Rahman, the executive director of the Dhaka-based Centre for Governance Studies think tank and a talk show host. “They don’t have a safe exit.”

The attackers complained that Westerners’ skimpy clothes and taste for alcohol were “encouraging local people to do the same thing,” according to witnesses. They then tortured and killed any hostage that couldn’t recite the Koran. When the siege was finally ended by a police raid, a total of 22 civilians—mainly locals, Italians, and Japanese—alongside five terrorists and two police officers were confirmed killed. Fifty others, mainly police, were injured.

It was the nadir amid a spike in ISIS-inspired Islamic terrorism that besieged Bangladesh, with more than 30 violent attacks targeting Hindus, academics, and secularist writers and bloggers over the previous 12 months. The atmosphere of fear became so pervasive that many restaurants banned foreign customers lest they become another target. Today, the leafy street where that carnage unfolded hosts only plush condos and a medical clinic. Yet the memory of the violence still provides legitimacy for Hasina’s security crackdown that persists to this day.

But it’s not just rocks and sticks on the street; Bangladesh’s judicial institutions have increasingly targeted any slight criticism of Hasina’s perceived enemies. On Sept. 15, two prominent human rights activists who tracked extrajudicial killings and disappearances were sentenced to two years in prison on nebulous charges, prompting an outcry from foreign governments including the U.S. Journalists, cartoonists, and students have also been targeted.

It’s a bizarre vendetta that stokes accusations of festering paranoia. Hasina may insist her record is exemplary—“food, clothing, housing, education, healthcare, job opportunities,” she reels off. “I’m doing it and I have done it”—but scratch the surface and things don’t look quite so rosy. Freedom House considers Bangladesh “partially free” and its economy is still reliant on agriculture, cheap garment exports, and the nearly $25 billion sent home from the 14 million-strong diaspora every year. Those remittances have played a key role in helping ease economic pressure, particularly as prices for fuel and other essential commodities have soared since the invasion of Ukraine.

Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index ranks Bangladesh 147 out of 180 countries worldwide—level with Iran and one place above Taliban-ruled Afghanistan. Hasina boasts that now in Bangladesh “every person has a mobile phone” and that the nation is due in 2026 to graduate from the U.N. grouping of Least Developed Nations. But that is by any measure an extremely low bar; by then the only remaining Asian members would be Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Cambodia.

Bangladesh’s critical role on the world stage is embodied by the Rohingya crisis. Drive an hour south of the seaside resort of Cox’s Bazar and a collection of bamboo huts covered with plastic sheeting emerges from the rolling countryside. Inside Kutupalong refugee camp, around one million stateless Rohingya refugees eke out a meager existence after fleeing government pogroms in western Myanmar, which claimed an estimated 24,000 lives. Children wallop threadbare soccer balls while women in niqab veils barter over samosas and sour plums. Those that fled brought little with them other than tales of slaughter, arson, and rape.

Read More: ‘There Is No Hope’: Death and Desperation Take Over the World’s Largest Refugee Camp

When asked about the Rohingya, Hasina reminds the world that “for six years my sister and myself lived outside the country as refugees, so we can feel their sorrow and pain.” But her government has proved deaf to demands to allow the refugees formal education and legitimate ways to earn a livelihood. Instead, the Rohingya’s welcome has expired. “It’s a big burden for us,” she says. “The U.N. and other organizations that are supporting [the Rohingya] here can also do the same inside Myanmar.”

The Rohingya crisis was never for Bangladesh to solve alone, of course, and the international community bears collective responsibility. Still, their plight raises fresh doubts regarding American influence in Dhaka. Historical baggage also plays a part. Bangladesh’s liberation struggle was opposed by the U.S., which valued its close ties to the Pakistani junta (famously dubbed “our most allied ally” by Nixon).

“Democracy has a different definition that varies country to country.”

Hostage to its size and geography, Bangladesh has artfully balanced U.S. ties with links to India, China, and Russia. The latter, in particular, has a significant history of people-to-people relations dating back to the Cold War, with Russian institutions hosting Bangladeshi students and civil society. The risk is that pressing too hard pushes Dhaka away from Washington and closer to Moscow and Beijing. To date, Hasina has both abstained from and supported U.N. resolutions calling for Russia to withdraw from Ukraine. “On some issues, we didn’t vote against Russia; then on some other issues, we vote against Russia,” she says, adding without a hint of irony: “Our position is very clear.”

It’s an approach designed to make Dhaka appear not openly antagonistic to either side. While Hasina has blocked more than 69 sanctioned Russian ships from docking in Bangladesh, in September Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov became the first ever top Russian official to visit, and Russian state-owned firm Rosatom is building the nation’s first nuclear plant 90 miles west of Dhaka. On Oct. 6, Bangladesh received the first shipment of Russian uranium for the plant, which is due online next July. Asked where to assign blame for the Ukraine war, Hasina issues a bromide reply: “They should all stop. Putin should stop and the U.S. should stop instigating the war and supplying money. They should give the money to the children.”

But that dream wasn’t necessarily a democratic Bangladesh. On Feb. 24, 1975, some six months before his assassination by renegade soldiers, Mujib dissolved all political parties and installed himself as head of a one-party state known as Baksal, ostensibly to see the nation through a state of emergency. Whether democracy would ever be restored is a divisive question, though critics have already dubbed Hasina’s regime “Baksal 2.0.” Even Hasina suggests Bangladesh exists in a gray zone: “Democracy has a different definition that varies country to country.”

—With reporting by Astha Rajvanshi/London