by Ajmal Khan A.T 24 March 2021

The south Indian state of Kerala has become one of the laboratories of the impacts of climate change in India over the past few decades. Looking at the changes in temperature, observed changes and experiences from the state, this article shows the peculiar vulnerability of Kerala to climate change.

Karkidakam (normally from mid-July to mid-August) is that month of the Malayalam calendar of Kerala when it rains incessantly. The old women of the upper caste Hindu households will often be found reading Kilippatu in this month, the dominant Malayalam version of the Ramayana, they call Karkidakam as the month of Ramayana. It’s believed that drinking Kanji, the typical rice soup of Kerala is a staple food during this rainy month, there is special rice soup in Karkidakam called Karkidaka Kanji. Ayurveda has special treatments in this month for the bodies that are tired working the whole year to rejuvenate the body and mind. These images of Karkidakam are also part of the collective Savarna Malayali nostalgia. However, this month is very difficult time for the laborers who have to step out of their homes and go for work. Hence, for the majority, meaning of Karkidakam is poverty and misery as they don’t find jobs or not being able to step out for work due to heavy rain. For the fishermen, sea will be prohibited by the annual trawling ban regulations; this is the month of scarcity and hunger for them. These sections call this month Kalla Karkidakam (a rogue season). This is also the month when the hill stations will have passing shades of clouds with a spectacular monsoon view, waterfalls will flow like silver linings on the green mountains. Rivers will overflow, and in the paddy fields, cannels and ponds often farmers will be found with fishing net or a fish trap. This is the month Kerala will be seen as green as possible in the whole year. However, Kerala has started to witness unprecedented ecological changes in the past decades.

The Raising Temperatures

Kerala’s ecology, climate and seasonal patterns have drastically changed over the last decades and it’s visible in all walks of life, changes in climate are more visible and felt. Karkidakam has become the month where temperate is more than 30 degree Celsius, it was mostly between 25 to 32-degree Celsius during the day time in 20201, of course this vary from region to region and district to district. Strangely, in 2019 the month of August was also recorded as the highest rain fall in the state since 1951 in the recorded history of the Indian Metrological Department2.

It has become hot and humid during Karkidakam if it’s not raining. Kerala is a tropical humid state and there were months in Kerala that were not very hot and humid, Karkidakam was one of them. The south west monsoon beginning from the month of June in Kerala continues until August- September and then north east monsoon arrive with comparatively less rain until early December when it slightly get cold across the state and particularly temperature drops in Wayanadu and Idukki, the hill districts. In Munnar, one of the favorite hill stations in the Idukki district had recorded the lowest temperature ever recorded as -3 degree Celsius in January 20203. The morning dew had turned into frost and it seemed like snow clad hills Munnar in pictures.

However, on the other side, most houses even in the villages have AC’s now. Air conditioners have become an essential home need in Kerala and it’s difficult to survive without them during the non-monsoon months when the temperature shoots up by 40-42 degrees. Especially in the Palakkad district, where the highest temperature in the planes of India were recorded in February 2020 and Kottayam district had recorded 38.5 Celsius as the highest temperature in India during the month of February 20204. The work schedule of the laborers who have to expose to sun light has changed for summer months, they get on to work very early in the morning and finish their work by the forenoon and some of them again get back to work after the sun set. In the month of February 2020 there was unusual rise in temperature 2-3 degrees Celsius above normal and the State Disaster Management Authority had warned Pregnant women, the elderly and children to be outdoors and avoid direct sunlight exposure. Since past few years, during every summer people die in Kerala due to sun burn and sun stroke5.

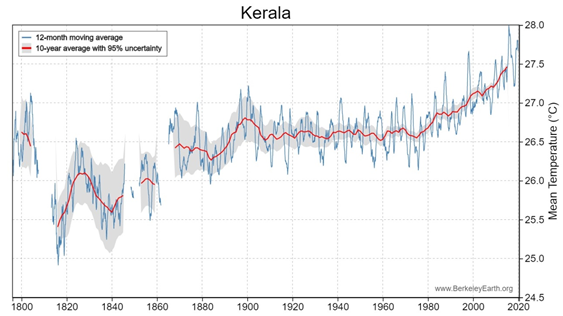

Graph: 1

Source: http://berkeleyearth.lbl.gov/regions/kerala

Graph 1 gives a historical sense of the average temperature changes from 1800 to 2020 in Kerala, it shows how temperature is increasing constantly with a significant increase from 1980’s and this is expected to further increase several folds in the coming decades. According to the Kerala State Plan on Climate Change in 2014, the temperature is likely to increase by 2 degree Celsius by 2050 and the minimum surface air temperature in the Western Ghats region may rise by 2 degree Celsius to 4.5 degrees.

For Keralites water scarcity and draught was something of a distant event that happens only in Rajasthan in the northern India or in the middle-eastern deserts. However, today most part of the state experience water scarcity during summer months which lasts from mid-February to June until monsoon arrive. Rivers, ponds and wells dry in the summer months to the extent that there is no water left. Then, local collectives, political parties, community organizations and voluntary groups supply water in many districts that face water scarcity and others buy water. The center had declared Kerala as draught affected state along with Tamil Nadu, Andra Pradesh and Karnataka in 2017 and according to the predictions by the State Draught Monitoring Cell of the Kerala State Disaster Management Authority the draught years are likely to increase in the state. This should also be looked at in the context of historically erratic and decreasing rain fall over India and particularly in the state of Kerala (IMD 2020, Krishnakumar et al 2009, Roxy et al 2017 and Pal, I., & Al-Tabbaa 2009) along with the mismanagement of the available water sources and lack of systematic water conservation plans.

Floods and the agriculture productivity

Another significant change is the annual floods now. Kerala only had floods in the history, Vellapokkathil (In the flood) is a famous short story by the well know Malayalam writer Thakazhi Shivashakara Pillai who wrote about the flood during 1924 when a devastating flood hit Kerala. After that, nobody in Kerala have the experience of what a flood looks like. However, 2018 was the year that everything changed. Kerala witnessed one of the biggest floods ever, a major part of the state was under water for a few days. Around 500 people died, many went missing, the society and economy of the state got devastated with an estimated economic loss of more than $3.8 million6. Kerala, however managed the flood in its own unique ways, help and support flowed from all corners of the world but it took many months for the state to recover. The flood in 2018 was looked at as a rare event occurred once in a 100 year, however, flood came again in 2019 during the same month. This time around 120 people died and with the experience of a flood last year the damage was relatively less, in 2020 it didn’t flood but there was a major landslide in Idukki due to heavy rain and 42 people died. Though the general assumptions about the anthropogenic reasons such as dams and barrages, hydropower projects, unsustainable mining, deforestation, catchment degradation and encroachments in the riverbeds and climate change have contributed to the cause and nature of floods (Pathak2020) the warnings about the probability of ecological catastrophes such as floods in Kerala (Gadgil et all 2011) were also ignored or no attention was paid.

These changes in the state have also impacted the agricultural productivity. Agriculture is vulnerable to the slightest changes in temperatures, hence crops like paddy, coconut, coffee, pepper and cardamom are visibly showing the impacts of these changes7. Wayanad district was known for its air-conditioned climate where coffee, pepper and other spices grow in surplus. However, now the coffee and pepper farmers complain of the raised temperature erratic rain fall, erosion of the forest cover and less productivity of coffee and pepper8. Cardamom farmers in Idukki have also started to feel the heat of climate change. They complain about the increased capsule rot in cardamom plants in the district9. There are also peculiar regional vulnerabilities within the state. This is where Kuttanad come, a region that is 2.2 meters below the sea levels and known as the rice bowl of the state has been in crisis with the flood and sinking of the land. Kuttanad is known for the globally important agriculture heritage system where they practice farming based on flood control and salinity management system. Farming in Kuttanad is based on an agricultural calendar which is changing; the farmers are preparing to update their implanting and swaying on to these changing calendars (Krishnanunni and Vishnu 2018). Chellnam a coastal village between the Arabian Sea and the backwaters near Kochi in Ernakulum district has been another case. Chellanam is highly susceptible to the coastal erosion and sea takes over the homes on the coasts every year. Half of the village is under water now due to coastal erosion since past many years making lives of the fisher folks more vulnerable10. These changes are of course not only peculiar to Kerala, similar changes are happening around the world and most part of India. However, the case of Kerala like many other vulnerable and fragile ecological regions in the country, is more visible and felt. When more hot and humid Karkidakam bid farewell to Kerala and the next month of the Malayalam calendar Chingam arrives, the changed Malayalam calendar gives us a glimpse of the changes and for the new generation in Kerala, Karkidakam along with rain, will also be a month of heat and humid now. What emerges from Kerala is first however, the need for more in-depth and local studies on the various impacts of climate change across the state and the need for an urgent comprehensive preparedness plan for the projected impacts of the changes in the state.

- In July- August 2020 most part of the state was recorded the highest temperature of 30-32 degree Celsius based on the IMD records. See https://malayalam.indianexpress.com/weather/kerala-weather-report-2020-july-30-rain-trivandrum-kozhikkode-kochi-400648/

- See August rain in Kerala highest in IMD data https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/thiruvananthapuram/august-rain-in-kerala-highest-in-imd-data/articleshow/70941896.cms Sep 2, 2019.

- Temperature touches freezing point at Munnar, The Hindu https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/temperature-touches-freezing-point-at-munnar/article30552037.ece

- Palakkad in Kerala records country’s highest temperature on Saturday. The Hindu buisnessline Weather, February 16, 2020.

Also see Kottayam records highest temperature in India, Mathrubhumi February 25,2020.

- Indian Metrological Department had issued heat-wave warming on 27-04-2016 in Kerala, first time such a warning was issued in the state and the temperature of Palakkad district was 6 degree Celsius above the normal with a record of 41.6 degree Celsius and from this year every year sunburn deaths were also reported from Palakkad. See Kerala State Disaster Management Plan, 2016. Government of Kerala. https://sdma.kerala.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Kerala%20State%20Disaster%20Management%20Plan%202016.pdf

- See Kerala Post Disaster Needs Assessment Floods and Landslides – August 2018 https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Climate%20and%20Disaster%20Resilience/PDNA/PDNA_Kerala_India.pdf

- Various studies conducted in the state about the changing climate and its impacts on agriculture productivity shows how the productivity of paddy, coconut, coffee, pepper and cardamom have significantly impacted and reduced in the state. See Saseendran et al 2000, Murugan et al 2012, Kandiannan et al 2014, Abhinav et al 2018, Pham et al 2019.

- See” why is the climate changing like this? https://www.in.undp.org/content/india/en/home/climate-and-disaster-reslience/successstories/pari-undp-series/climate-wayanad.html

- See In Idukki, Cardamom feels the heat of climate change https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/in-idukki-cardamom-feels-the-heat-of-climate-change/article29429170.ece

- See Assessment of Climate Change Induced Vulnerability of Fisher folk in Kerala-A case study of Chellanam. University of Kerala IUCAE Report No. 25 / 2019. http://www.iucae-ku.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Saradadevi.pdf

References

Krishnakumar, K. N., Rao, G. P., & Gopakumar, C. S. (2009). Rainfall trends in twentieth century over Kerala, India. Atmospheric environment, 43(11), 1940-1944.

Hunt, K. M., & Menon, A. (2020). The 2018 Kerala floods: a climate change perspective. Climate Dynamics, 54(3), 2433-2446.

Pal, I., & Al-Tabbaa, A. (2009). Trends in seasonal precipitation extremes–An indicator of ‘climate change’in Kerala, India. Journal of Hydrology, 367(1-2), 62-69.

Pham, Y., Reardon-Smith, K., Mushtaq, S., & Cockfield, G. (2019). The impact of climate change and variability on coffee production: a systematic review. Climatic Change, 156(4), 609-630.

Murugan, M., Shetty, P. K., Ravi, R., Anandhi, A., & Rajkumar, A. J. (2012). Climate change and crop yields in the Indian Cardamom Hills, 1978–2007 CE. Climatic change, 110(3-4), 737-753.

Thakkar, H. (2018). Role of dams in Kerala’s flood disaster. Economic & Political Weekly, 20-23.

Pathak, S. (2020). Comparing Floods in Kerala and the Himalayas. Economic & Political Weekly, 55(5), 27.

Krishnanunni and Menon (2018) Kuttanad after the Flood, Economic & Political Weekly, 53(47) https://www.epw.in/journal/2018/47/postscript/kuttanad-after-flood.html

Gadgil, M., Krishnan, B. J., Ganeshaiah, K. N., Vijayan, V. S., Borges, R., Sukumar, R., … & Gautam, S. P. (2011). Report of the Western Ghats ecology expert panel. submitted to the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India.

Roxy, M. K., Ghosh, S., Pathak, A., Athulya, R., Mujumdar, M., Murtugudde, R., … & Rajeevan, M. (2017). A threefold rise in widespread extreme rain events over central India. Nature communications, 8(1), 1-11.

Nair, A., Joseph, K. A., & Nair, K. S. (2014). Spatio-temporal analysis of rainfall trends over a maritime state (Kerala) of India during the last 100 years. Atmospheric Environment, 88, 123-132.

2014, Kerala State action plan on climate change, Department of Environment and Climate Change, Government of Kerala.

IMD (2020) Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes over Kerala State; Climate Research and Services India, Metrological Department, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Pune. ESSO/IMD/HS/Rainfall Variability/14(2020)/38

http://imdpune.gov.in/hydrology/rainfall%20variability%20page/kerala_final.pdf

KSDMA(2018)Drought – Situation Assessment Report, 2017 (1 st June 2016 – 31st March, 2017). Kerala State Drought Monitoring Cell, Kerala State Disaster Management Authority Department of Revenue and Disaster Management Government of Kerala. https://sdma.kerala.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Drought-Situation-Assessment-2017-April.pdf

Kerala State Disaster Management Plan, 2016. Government of Kerala. https://sdma.kerala.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Kerala%20State%20Disaster%20Management%20Plan%202016.pdf

Kerala Post Disaster Needs Assessment Floods and Landslides – August 2018 https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Climate%20and%20Disaster%20Resilience/PDNA/PDNA_Kerala_India.pdf

Temperature Anomalies over Kerala and Lakshadweep. Indian metrological Centre, Government of India, Trivandrum.

https://mausam.imd.gov.in/Thiruvananthapuram/mcdata/max%20and%20min%20anomalies.pdf

Regional Climate Change: Kerala, Berkley Earth

http://berkeleyearth.lbl.gov/regions/kerala

UNDP, Why is the climate changing like this? Vishaka George https://www.in.undp.org/content/india/en/home/climate-and-disaster-reslience/successstories/pari-undp-series/climate-wayanad.html