Catholic priest Father Abid Habib followed Muslim funeral traditions after the death of his father.

UCA news 16 June 2020

A cleric read aloud the Salatul Janazah (Islamic funeral prayer) as the former Capuchin superior joined his relatives in burying the coffin in the Muslim graveyard of Chak Hakeem Imam-ud-Din in Punjab province this month.

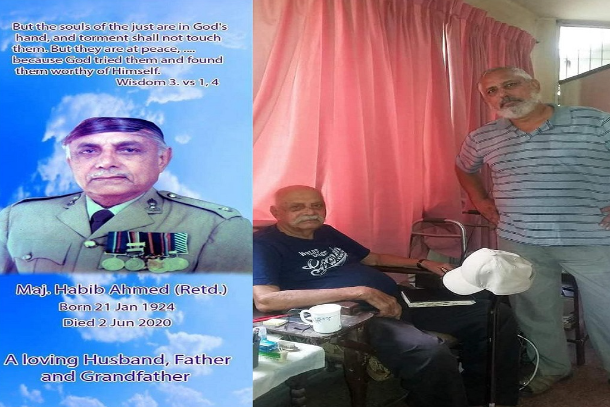

Retired major Habib Ahmed, 96, was among the first recruits to the Pakistan army soon after independence. His family shunned him after he married Maria, a Catholic from Goa, India, in 1950 at Sacred Heart Cathedral in Lahore. She was buried in a Catholic cemetery in 2007.

Ahmed’s six Catholic children prayed silently as Muslim relatives recited tasbih at Rasm-e-Qul, the three-day congregational prayers.

More than 20 priests concelebrated his Requiem Mass led by Father Habib at St. Mary’s Church in Lahore. The priest thanked all for attending the Mass despite the coronavirus pandemic.

“I couldn’t administer the sacrament of anointing the sick since he didn’t know about the sacraments. He suffered for us being Christians,” Father Habib told UCA News.

“Sometimes he expressed displeasure at mother praying in church. We conducted daily family prayers without him. He used to go for a jog during Mass. In grade five, he called me a bad boy for studying the catechism. In grade 13, my friend used to invite me to become a Muslim as per my father’s faith,” he recalled.

According to the priest, the increasing questions inspired him to explore the Bible and the Quran.

“I would fiercely counter their questions but that was before 1980 when the military government of General Zia-ul Haq started adding additional clauses to the blasphemy law. I wanted to follow in the footsteps of my father but failed the army recruitment test twice. The emptiness kept growing,” he said.

In 1976, he met Father Andrew Francis, who later became the bishop of Multan, during the silver jubilee celebrations of St. Mary’s Minor Seminary in Lahore.

“He lauded my altar boy robe and talked about another priest in Karachi whose father was also a Muslim. It finally cleared the obstacle. My mother was referred to another elderly priest for further counseling. Finally, the death of my elder brother changed my father forever,” said Father Habib.

“My father’s biggest sacrifice was allowing me to become a priest. He accompanied me to the Capuchin house in 1979. My relatives were kept in the dark about the priesthood.”

The 63-year-old priest has served as regional coordinator of the Justice and Peace Commission of the Catholic religious major superiors, president of the Major Superiors Leadership Conference of Pakistan, seminary professor and director of Joti Educational and Cultural Centre in Hyderabad Diocese of Sindh province.

Dialogue of life

With his Islamic background, Father Habib pursues interfaith dialogue in Muslim-majority Pakistan, where religious minorities often face persecution and violence. From parishes to prisons, the writer of several research papers on Islam regularly holds peace sittings with Muslims.

Father Habib has also converted 10 Muslims. The two-month process involves instructions from a priest, learning about the Christian faith, the teachings of the Bible and the Church as well as evaluation of those interested.

“All of them were inspired by their neighbors, not a priest or a nun. They were baptized on Easter vigils in small churches away from media attention,” he said.

‘Interfaith dialogue has its roots in day-to-day life. I dialogue about ecology and common issues with ordinary people. The clerics only focus on sawab [spiritual merit]. I don’t stop Muslims standing outside listening to my homilies.”

With conversions come challenges. Pakistan’s Penal Code does not mandate the death penalty for apostasy. However, it is interpreted as a capital crime by traditional clerics and the Council of Islamic Ideology — a constitutionally mandated body tasked with ensuring that all legislation complies with the Quran and Sunnah (life of Prophet Muhammad).

In order to avoid attention, Father Habib gives appointments to candidates according to different schedules. However, in the late ‘90s, police agencies tracked Father Habib while he was serving in Lahore.

“My first task for Muslim candidates is about finding Jesus in the Quran. I was giving instructions to a couple when they fled after seeing a visitor in church and hid in the friary. Upon individual investigation, both accused the other of being a spy. They were banned from the church. Their miscommunication saved my life,” he smiled.

Father Habib now plans to move to Dubai to continue his mission of interreligious dialogue.

Bishop Samson Shukardin of Hyderabad expressed “heartfelt” condolences to the family of Habib Ahmed over their loss.

“Military personnel follow strict standards, but Ahmed gave us a gift of a dedicated priest. This is a rare example of interfaith harmony based on love,” he said.