Alka Kurian, University of Washington, Bothell

Women are among the strongest opponents of two new laws in India that threaten the citizenship rights of vulnerable groups like Muslims, poor women, oppressed castes and LGBTQ people.

The Citizenship Amendment Act, passed in December 2019, fast-tracks Indian citizenship for undocumented refugees from Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Pakistan – but only those who are non-Muslim. Another law – the National Register of Citizens – will require all residents in India to furnish extensive legal documentation to prove their citizenship as soon as 2021.

Critics see the two laws as part of the government’s efforts to redefine the meaning of belonging in India and make this constitutionally secular country a Hindu nation.

Since Dec. 4, 2019, Indians of all ages, ethnicities and religions have been protesting the new citizenship initiatives in scattered but complementary nationwide demonstrations. The uprisings have persisted through weeks of arrests, beatings and even killings across India by the police.

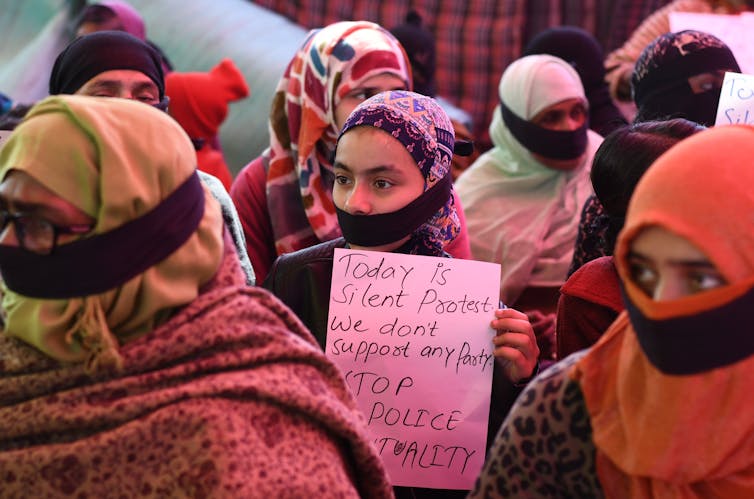

But the most enduring pocket of resistance is an around-the-clock sit-in of mostly hijab-wearing women in a working-class Delhi neighborhood called Shaheen Bagh.

Women take charge

Since Dec. 15, 2019, women of all ages – from students to 90-year-old grandmothers – have abandoned their daily duties and braved near-freezing temperatures to block a major highway in the Indian capital.

This is a striking act of resistance in a patriarchal country where women – but particularly Muslim women – have historically had their rights denied.

The Shaheen Bagh protests are as novel in their methods as they are in their makeup. Protesters are using artwork, book readings, lectures, poetry recitals, songs, interfaith prayers and communal cooking to explain their resistance to citizenship laws that, they say, will discriminate against not just Muslims but also women, who usually don’t have state or property papers in their own names.

On Jan. 11, women in the Indian city of Kolkata performed a Bengali-language version of a Chilean feminist anthem called “The Rapist is You.” This choreographed public flash dance, first staged in Santiago, Chile in November 2019, calls out the police, judiciary and government for violating women’s human rights.

A dangerous place for women

India is the world’s most dangerous country for women, according to the Thompson Reuters Foundation. One-third of married women are physically abused. Two-thirds of rapes go unpunished.

Gender discrimination is so pervasive that around 1 million female fetuses are aborted each year. In some parts of India, there are 126 men for every 100 women.

Indian women have come together in protest before, to speak out against these and other issues. But most prior women’s protests were limited in scope and geography. The 2012 brutal gang rape and murder of a 23-year-old Delhi woman – which sparked nationwide protests – was a watershed moment. All at once, the country witnessed the power of women’s rage.

The current women-led anti-citizenship law demonstrations are even greater in number and power. Beyond Shaheen Bagh, Indian women across caste, religion and ethnicity are putting their bodies and reputations on the line.

Female students are intervening to shield fellow students from police violence at campus protests. Actresses from Bollywood, India’s film industry, are speaking out against gender violence, too.

Women’s secular agenda

With their non-violent tactics and inclusive strategy, the Shaheen Bagh women are proving to be effective critics of the government’s Hindu-centric agenda. Their leaderless epicenter of resistance raises up national symbols like the Indian flag, the national anthem and the Indian Constitution as reminders that India is secular and plural – a place where people can be both Muslim and Indian.

The Shaheen Bagh movement’s novel and enduring strategy has triggered activism elsewhere in the country.

Thousands of women in the northern Indian city of Lucknow started their own sit-in in late January. Similar “Shaheen Baghs” have sprung up since, in the cities of Patna and even Chennai, which is located 1,500 miles from Delhi.

Global women’s spring

India’s Shaheen Bagh protests form part of a broader global trend in women’s movements. Worldwide, female activists are combining attention to women’s issues with a wider call for social justice across gender, class and geographic borders.

In January 2019 alone, women in nearly 90 countries took to the streets demanding equal pay, reproductive rights and the end of violence. Young women were also at the forefront of the 2019 pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, Lebanon, Sudan, Brazil and Colombia.

As I write in my 2017 book, such inclusive activism is the defining characteristic of what’s called “fourth wave feminism.”

There isn’t a common definition of the first three feminist waves. In the United States, they generally refer to the early 20th century suffragette movement, the radical women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s and the more mainstream feminism of the 1990s and early 2000s.

Fourth wave feminism appears to be more universal. Today’s activists fully embrace the idea that women’s freedom means little if other groups are still oppressed. With its economic critique, disavowal of caste oppression and solidarity across religious divides, India’s Shaheen Bagh sit-in shares attributes with the women’s uprisings in Chile, Lebanon, Hong Kong and beyond.

The last time women came together in such numbers worldwide was the #MeToo movement, a campaign against sexual harassment which emerged on social media in the United States in 2017 and quickly spread across the globe.

Shaheen Bagh and similarly far-reaching women’s uprisings underway in other countries take #MeToo to the next level, moving from a purely feminist agenda to a wider call for social justice. Women protesters want rights – not just for themselves, but human rights for all.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Alka Kurian, Senior Lecturer, School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences, University of Washington, Bothell

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.