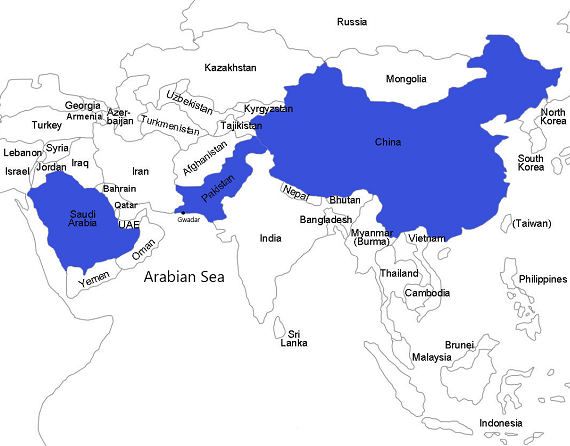

Pakistan received substantial US military and financial aid since 2001, and the Trump administration canceled those payments in 2018, with the president suggesting that the country doesn’t “do anything for us.” Pakistan still has support from China, an ally since 1962, and Saudi Arabia also steps forward to invest. The benefactors have two goals in mind – propping up a struggling neighbor and positioning Pakistan as a link for two national economic plans, China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the Saudi Vision 2030, explains author Dilip Hiro. China has long viewed Pakistan as a strategic connection to the Arabian Sea, along with the region’s oil and other resources. Saudi Arabia, criticized by Western businesses and institutions for its role in the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at a Saudi consulate, is keen to build new ties. The Pakistani port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea, part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, is a prominent transportation hub for new connections, including a host of energy and infrastructure projects as well as trilateral military sales and activities. – YaleGlobal

China and Saudi Arabia step in to support Pakistan after the US cuts $2.1 billion in financial and military aidDilip HiroThursday, March 7, 2019

LONDON: A trilateral alliance of China-Pakistan-Saudi Arabia, driven by geo-economic interests, is emerging, with the Pakistani port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea as its hub. This builds upon a geopolitical foundation dating back to the mid-1960s. With the Trump administration cutting $2.1 billion worth of financial and military aid to Islamabad, neighboring China and friendly Saudi Arabia have taken cash-strapped Pakistan under their wings to strengthen its economic base. In contrast to the wavering Washington-Islamabad relationship, Sino-Pakistani ties have become tighter with each passing decade.

China’s interest in Gwadar dates back to 2001 when the visiting Chinese Prime Minister Zhu Rongji signed an agreement with Pakistan to turn the facility into a deep-water port. China covered three-quarters of the $250 million cost of building the port commissioned in 2007. Yielding to pressure by the United States, Pakistan’s president opted for giving the 40-year operating lease to PSA International, owned by the Port of Singapore Authority. The port was not operationally profitable, and Pakistan transferred control to state-owned China Overseas Ports Holding Company Limited, or COPHCL, in 2013.

Gwadar is strategically important for China, as 60 percent its imported oil originates in the Gulf region and passes through the Strait of Hormuz, a gateway for a third of the globe’s traded petroleum. The port is 650 kilometers from this strait whereas the Chinese port of Xingjian is 15,000 kilometers away. Crude oil arriving at Gwadar is to transported to China’s far western Xinjiang Autonomous Region overland by pipeline and the upgraded 1,300-kilometer Karakoram Highway, which opened to public in 1986.

During Chinese President Xi Jinping’s 2015 visit to Islamabad, Pakistan and China inked an agreement to start work on the $46 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, or CPEC, a network of infrastructure and energy projects. The corridor is an integral part of Beijing’s $900 billion One Belt, One Road, later renamed Belt and Road Initiative, that was unveiled in 2013. With that, Gwadar became the end point for one of six economic corridors stemming from China. The total investment in CPEC rose to $62 billion.

In 2016, CPEC became partially operational when Chinese goods were transported over the Karakoram Highway to Gwadar Port for maritime shipment to the Horn of Africa and the Middle East. Five months later, the Pakistani government leased Gwadar Port to the COPHCL for 40 years, authorizing the Chinese port holding company to carry out development work on the port and the vast adjoining free economic zone. Scale of the enterprise could be judged by Pakistani media reports suggesting that Gwadar’s population would rise exponentially to 500,000 by 2023, with gated residential quarters being constructed for about 10,000 Chinese and Pakistani professionals and their families.

By all accounts, the future of the Gwadar port and the free economic zone is rosy. That was why during Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Sultan’s February visit to Islamabad, $8 billion of the $20 billion his government committed to invest in Pakistan were earmarked for an oil refinery in Gwadar.

With its foreign exchange reserves at $506 billion, the fourth highest in the world. Saudi Arabia can easily invest the sum it promised Islamabad – and even throw a $6 billion lifeline to save Pakistan from defaulting on servicing a huge loan secured from the International Monetary Fund in 2013. However, the kingdom did so only after Pakistan’s newly elected Prime Minister Imran Khan agreed to attend October’s Future Investment Initiative conference in Riyadh, boycotted by Western governments and financial institutions following the grisly murder of the dissident Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul earlier that month.

Underlying these moves by the Saudi Kingdom is the realization, shared by China, that only by building new infrastructure in Pakistan and repairing its dilapidated facilities can its chronic economic ills be cured.

While China is forging ahead with Xi’s signature Belt and Road Initiative, Riyadh’s overambitious economic blueprint – Saudi Vision 2030, announced in 2016, to wean the kingdom away from oil, diversify its economy, bolster public services, build infrastructure and shore up its defense industry – has failed to take off. Most of the funding for the Saudi initiative was to have come from phased privatization of state-owned Saudi Aramco, the globe’s largest oil corporation. The $100 billion initial public offering of the company’s 5 percent share, expected in 2018, was postponed indefinitely due to legal concerns and the kingdom’s failure to achieve its total desired valuation of $2 trillion, based on oil barrel selling for a minimum of $70.

Briefed on the hurdles facing Saudi Vision 2030, Xi broached the subject with Bin Salman during his February visit to Beijing. “Our two countries should speed up the signing of an implementation plan on connecting the Belt and Road Initiative with the Saudi Vision 2030,” he said. No details were released.

In contrast, the Trump administration is unlikely to end its shunning of Islamabad. In January 2018, Donald Trump canceled government plans for $1.3 billion of military aid to Pakistan and announced on Twitter that Pakistan had “given us nothing but lies and deceit,” accusing the nation of providing “safe haven to the terrorists we hunt in Afghanistan.” In addition, Washington cut $800 million to reimburse Islamabad for expenses incurred to support the US-led coalition’s counter-insurgency operations.

Altogether, since 9/11, Pakistan received more than $33 billion in US assistance, including more than $14 billion from Washington’s Coalition Support Funds.

By contrast, China’s diplomatic entente with Pakistan after the 1962 Sino-Indian War graduated to military cooperation with the common aim of containing the power of India, then backed by the Soviet Union. China’s military aided its Pakistani counterpart to set up ordnance factories with improved technologies. China started selling battle tanks and armored vehicles to Pakistan. Later Chinese military engineers designed tailor-made advanced weapons for Pakistan’s army, and issued licenses for domestic production.

Around the turn of the century Beijing started turning attention to the Pakistani air force and navy. This led to the co-production of China’s JL-8 fighter aircraft in Pakistan and China. In 2009, Pakistan became the first foreign country to receive China’s advanced fighter aircraft, JL-10. The two countries also turned to joint development of the JF-17 Thunder fighter aircraft and K-8 Karakorum training aircraft.

During a 2015 visit of Pakistan’s Army Chief, General Raheel Sharif, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi described Pakistan as China’s “irreplaceable, all-weather friend.” Three months later, China agreed to sell Pakistan eight conventional submarines worth $5 billion, the biggest arms sale by Beijing. In addition, China’s weapons deliveries to Pakistan include naval patrol vessels, unmanned aerial vehicles and surface-to-air missiles. Last December, a Special Forces contingent of China’s military arrived in Pakistan to participate in the sixth Pakistan-China joint military exercise.

Pakistani troops played a major role in overpowering the armed militants who had seized the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979, threatening the Al Saud dynasty. Since then the nation has signed periodic contracts with Riyadh to post its soldiers in the kingdom. Pakistan has lent military expertise to Saudi Arabia, and the two nations conduct joint exercises annually. Joint naval exercises, called Naseem Al-Bahr, began in 1993 and have become a biennial feature. With Pakistan becoming a declared nuclear power in 1998, its strategic value to Saudi Arabia, wary of rival Iran’s nuclear ambitions, has risen sharply.

On the other side, India and the United States are worried about the prospect of China building a military base at Jiwani, 60 kilometers west of Gwadar, which already hosts a small naval base and airport.

Dilip Hiro’s latest and 37th book is Cold War in the Islamic World: Saudi Arabia, Iran and the Struggle for Supremacy, published by Oxford University Press, New York; Hurst & Co., London; and HarperCollins India, Noida). Read an excerpt.