3 September 2018

Some 1,000 people have been sent to detention centres in India’s north-eastern state of Assam after being declared illegal citizens. BBC Hindi’s Nitin Srivastava reports on what life has been like for some of them.

Ajit Das, 33, fears he may never recover from the three months he spent in a detention camp in the city of Silchar.

He was granted bail a few weeks ago to help his wife care for their four-year-old daughter, who is autistic.

During his time in the camp, Mr Das lost his job, his health deteriorated and his wife spent a large portion of their savings to visit him regularly.

“I lost 5kg in three months. The food was awful and often half-cooked,” he says.

Mr Das was sent to the detention camp after he was declared an illegal citizen by a special court set up to identify illegal immigrants from neighbouring Bangladesh.

- Will India really deport four million people?

- What happens to India’s four million ‘stateless’ people?

Since 1985, these special courts have heard some 85,000 cases of people suspected of being foreigners by India’s border police. They have reached decisions on the cases of at least 1,000 people, who are now in six detention centres across Assam.

The government is yet to release information on the status of the remaining cases.

Illegal migration from Bangladesh to India’s north-east, including Assam, has always been a serious concern. Estimates of illegal foreigners range from four million to 10 million – and they have a sizeable presence in at least 15 of Assam’s 33 districts. Most of them are engaged in agriculture.

Mr Das says his parents arrived from Bangladesh in the 1960s and they died a few years ago. He says he was born in India but the court classified him as a “doubtful Indian citizen”, claiming that his documents did not prove it.

Although the citizenship of Mr Das’s wife has not been questioned, their two children have been found to be illegal citizens. The couple have hired a lawyer to challenge the government’s decision but Mr Das says that is costing them a lot of money.

Although those who have been declared foreigners can appeal the decision, it will be a lengthy process that could take months or even years. Until they get a final decision on their legal status, Mr Das and his family will have to live in limbo.

However it is unclear what will happen to them even if they lose the appeal as India has no official treaty with Bangladesh in relation to cross-border illegal immigration.

Earlier this month, the Indian government published a list of Assam’s proven citizens, which left out the names of some four million people. This has complicated the situation further as the government is yet to clarify if the two processes overlap in any way.

Meanwhile, Mr Das is afraid that his bail might be cancelled at any time, forcing him to return to the camp.

He says the camp was a large but cramped room in a red building that houses a prison. All the detention camps in Assam are located within a prison compound.

Mr Das recalls at least 35 people eating and sleeping in the single room that was the Silchar camp. And they all used one toilet which had no locks – they waited for 30 minutes every morning for their turn.

He was woken up each morning at 05:00 (23:30 GMT) by a thunderous shout. He had to be ready within the hour or he would miss the daily cup of tea served with two biscuits. Everyone was then ushered out of the room to spend the day out in the open ground surrounded by 40ft (12m) high brick walls.

Lunch comprised of rice, pulses and a vegetable, while dinner was hurriedly served before 17:00. They had to return indoors by 18:00, after which the doors would be locked.

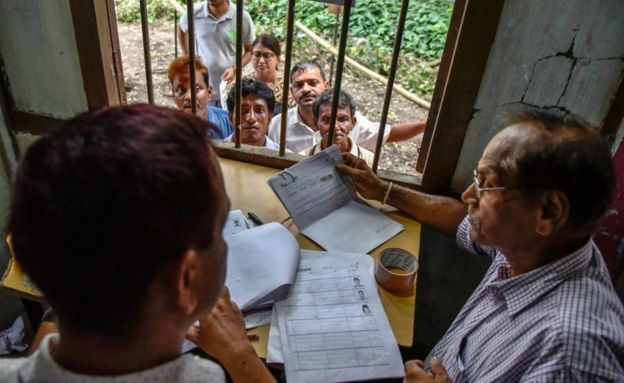

Outside the camp, people can be seen queuing through the day to meet family members who were inside the walls. Most of them will meet for just 10 minutes, separated by a row of thick iron rods. Those who can afford it buy themselves some extra time.

Mohammed Yunus (his name has been changed on his request) says he has visited his father in the Silchar camp every week since he was sent there a year ago.

“Despite having the right to vote and owning a small piece of land, we are forced to prove our citizenship in court,” he says.

Some people have been declared foreigners due to bureaucratic errors – such as Suchandra Goswami, a part-time music instructor.

She received a legal notice in 2011 to prove her citizenship. She says she did not respond since her first name was misspelt. But in 2015, she was arrested. She was in prison for three days before she was able to secure bail.

“Three days in prison for a spelling error was enough to destroy my confidence in everything,” says Ms Goswami. “I was sobbing for three nights.”

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESMs Goswami says she was placed in a regular prison, not a detention camp. Mr Das, too, says he was first put in a prison cell with people who “were serving time for murder or rape” and he was moved to the detention centre only after he complained.

India’s Supreme Court recently asked both the federal and state governments to submit reports on living conditions in the camps.

“Some [of those identified as “doubtful citizens”] have had to stay with prisoners in a common jail because of space constraints,” S Lakshmanan, a district official, told BBC Hindi. “But we are committed to improving living conditions. We provide free medical aid and we are in the process of overcoming staff shortages.”

Chandradhar Das, who claims he is more than 100 years old, could not escape the detention camp either. And he can barely walk without support.

But his name made it to the “doubtful Indian citizen” category and despite his age, he spent three months in a camp. He says he managed with the help of others in the camp.

“I won’t die before I prove my Indian citizenship,” he says.