The recently concluded 20th congress of the Chinese Communist Party will be best remembered for what it revealed and what it obscured. BENJAMIN HO notes that images of former president Hu Jintao being escorted out of the meeting on the last day will be etched in the minds of international observers even as Xi Jinping keeps the world guessing on what happens next, both in terms of the political succession and China’s foreign affairs.

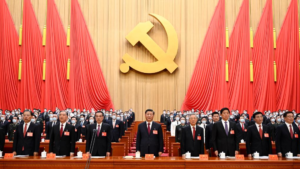

Xi Jinping cementing his place as the most powerful leader of the Chinese Communist Party since Mao. Photo from CGTN.

To many international observers, the week-long 20th congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), held from 16 to 23 October 2022, will be best remembered for President Xi Jinping’s thorough consolidation of power within the party. This was symbolically evidenced by the image of a forlorn-looking former Chinese president Hu Jintao being escorted out of the meeting on the last day. Beyond this, however, what were some of the key storylines that have emerged in the course of the week-long meeting? And, what would they mean for the future of China?

Political Allegiance above All

Hindsight is always 20/20, and there were all sorts of speculation as to who would make the final list of the CCP’s Politburo Standing Committee. The final line-up however suggested a more straight-forward selection logic: political allegiance to Xi trumps everything else. Whether there was any horse-trading, compromise or concessions behind the scenes would never be known, but it would seem that in the final reckoning those who would lead China into the future are those who demonstrated loyalty to Xi in the past.

In this respect, governing competency is considered less important than political compliance as the former attribute can be trained and picked up along the way but not the latter. The example of Li Qiang — who will replace Li Keqiang as Chinese premier — was clear proof that those who obeyed Xi would be rewarded and those who challenged him dropped. More importantly, such a line-up will remove all speculation regarding any competing factions within the party’s top echelons — at least for the next few years — and any uncertainty that such factional struggles within the party might bring about.

China and the International Security Environment

In terms of foreign affairs, China increasingly views the world in a binary, the West-against-us manner. As observed by my colleague Stefanie Kam, the need to strengthen China’s image as a “great power”, construct a global order favourable to Beijing’s core interests, and acquire a global leadership role commensurate with the CCP’s perception of the country’s status has been a core foreign policy imperative.

At the same time, strategic competition with the United States has led China to view the world with general suspicion and to categorise countries it comes into contact with as being either friends or enemies of China. As it stands, the CCP is seized with a virtual siege mentality, suspecting that the West — led by the United States — is out to contain its rise, including wanting to destabilise it internally by overthrowing its political regime. The term “peaceful rise” — a slogan from Hu Jintao’s days — is not spoken about much today, suggesting that for President Xi, “peaceful rise” was only the first step to a bigger objective, which is that the Chinese nation should be rejuvenated and China respected as a great power internationally.

It is no secret that China views Asia as its backyard and the region where its strategic interests are mostly concentrated. The fact that Foreign Minister Wang Yi and China’s ambassador to the United States, Qin Gang, have both been promoted to the Politburo shows that Xi approves of what they have done over the years in defending Beijing’s interests internationally, while promoting and projecting China’s strength regionally. Barring Xi’s change of heart, we are likely to witness a continuation of the existing tensions between China and the United States and other Western countries. In this respect, Xi is unlikely to worry about what the rest of the world might think or say about China’s international behaviour so long as he retains the broad support of the party and the Chinese people.

COVID-19 and China

The need to legitimise the CCP’s rule among the Chinese people then ranks as President Xi’s foremost priority. Given this priority, China’s COVID-19 pandemic response is one that is borne not purely out of medical science or health concerns, but rather out of concerns that the party — and the entire CCP edifice — should be portrayed as being different and better than Western governments. As I have argued elsewhere, Xi cannot back down on the pandemic response, for doing so would represent a severe loss of face for him and the CCP, which in turn would delegitimise both him and the party in the eyes of its own people.

There is still ongoing speculation about when the Chinese government would re-open its borders and reintegrate China with the rest of the world, and whether Xi — his position now entrenched — would roll back the harsh pandemic-related measures of the past two years. Given Xi’s maximalist approach to safeguarding Chinese security, it is unlikely that any form of grand re-opening would take place as this would send the signal that China has no choice but to accept reality for what it is. Instead, Xi is likely to insist that any form of re-opening should take place on his terms and that the party remains in control.

Indeed, the need for control is a central tenet of Marxist-Leninist thinking, as evidenced by the drama of former president Hu Jintao’s ignominious exit from the party congress. Whether the event was choreographed or unexpected is not so much the point; what is more pertinent is that Xi had cleverly utilised Hu’s awkward response to send a very public signal, both domestically and internationally, that he is in control. The extent to which this narrative of control can be sustained in the coming years will be a vital factor in China’s international relations and domestic politics.

Benjamin HO is an Assistant Professor in the China Programme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, and Deputy Coordinator of the Master of Science (International Relations) programme.