Tanzil Shafique, University of Melbourne 2 August 2019

Imagine a community of 200,000. Convivial, walkable, six times the density of Manhattan but with a smaller ecological footprint. It provides low-cost services and affordable housing mixed with productive uses such as recycling, farming and trading. It’s a city within a city.

But the streets aren’t wide enough to allow cars. The houses seem makeshift and the drains need work. The adaptations make it look like a place under perpetual construction.

In fact, the landlords and local leaders have incrementally built their houses and urban amenities over the last 40 years. They have self-organised to provide services such as gas, electricity and water. Non-government organisations (NGOs) have often provided extensive support to help with this process.

Read more: Design in the ‘hybrid city’: DIY meets platform urbanism in Dhaka’s informal settlements

The only catch is this community has been built on unused public land. Now the residents face threats of resettlement to allow for “development” projects planned by the state. After spending six months in such a place, I can attest to their simultaneous desire to live their lives and the fear of uprooting that underlies their daily life.

The story of a billion people

The place is Karail, the largest informal settlement in Dhaka, but the story is not particular to there. A billion people live in such places around the world. That number is slated to reach 3 billion people in the next 30 years.

This means informal settlements are one of the major ways developing cities are being produced. Conventional planning approaches such as slum clearance, cookie-cutter high-rises, peripheral resettlement and back-to-village programs have often failed to manage them.

UN-Habitat, the body with global responsibility for issues of urban growth, advocates city-wide slum upgrading and integration with metropolitan plans. Such programs are explicitly “participatory” and inclusive. Specifically, UN-Habitat recommends member states “recognise the rights and contributions of slum dwellers and change the view that they are illegal”.

Read more: Will Habitat III defend the human right to the city?

However, these recommendations are non-binding. It is up to the state and NGOs to implement policies on the ground. While funding agencies and local civic bodies have important roles too, they are ineffective in formulating the upgrading programs by themselves.

Read more: When planning falls short: the challenges of informal settlements

What’s the plan for Karail?

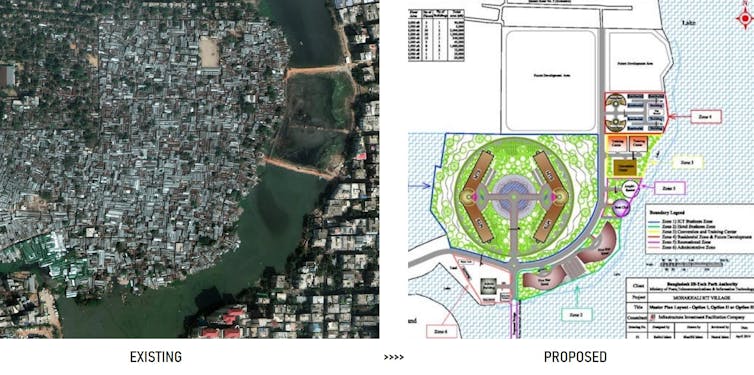

In Karail’s case, the land belongs to the Ministry of Science and Information & Communication Technology (MoSICT). It plans to establish a software technology park to replace the settlement. In 2014, several NGOs providing pro bono legal aid filed petitions in court challenging the authority to carry out evictions on such a massive scale. The final verdict is still pending, but the word on the streets in Karail is that the wheels are in motion to make the project happen by any means.

If the project proceeds, the demolitions will begin soon. The resettlement plan for the project proposes six options, none of which are slum upgrading.

In the best-case scenario, about 6,000 economy flats (roughly 25 square metres) will be built on site. Remember, at least 40,000 families live in Karail. The other options – including off-site resettlement or cash compensation – are far worse.

The draft plan shows no understanding of the site as an existing city, nor are there any attempts to integrate slum upgrading into the project, as UN-Habitat recommends. Note that the objective of the project is “to establish knowledge-based industries contributing to the national economy and helping achieve the goals of Vision 2021: Digital Bangladesh”. The project is predicted to create 30,000 jobs.

Such is the cruel irony of “development”. For an estimated investment of AU$300 million, the project will generate 30,000 future jobs, replacing the estimated 116,000 jobs that Karail supports. The project will displace 40,000 families from their current affordable housing and build high-rise apartments to house only 6,000.

In a city already on the verge of collapse with traffic congestion, the project is set to attract more traffic to the centre. Vehicle-based infrastructure will replace the non-motorised walkable neighbourhood of Karail. The cost of losing the accumulated social capital of the people of Karail only makes it worse.

‘Development’ that fails people

Such “development” in pursuit of a techno-ideological spectacle, without a sense of equitable well-being, is empty and is particularly threatening to informal settlements due to land value. Even when the state operates with the best of intentions and provides off-site resettlement, it has proven to be disastrous in Bangladesh, as exemplified by the Bhashantek Rehabilitation Project.

As Karail’s case shows, conventional “development” and policymaking do not know how to deal with such settlements. Planning is conducted with half a mind in the absence of empathy. “Inclusive cities” and “sustainable development” become empty motherhood slogans.

New practices can only emerge when we begin to learn how the other half lives and become allies in their struggle. Will Karail survive the onslaught of development? Well, it has survived decades of adversity so far and there is never any scarcity of hope.

Tanzil Shafique, PhD Researcher in Urban Design, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.