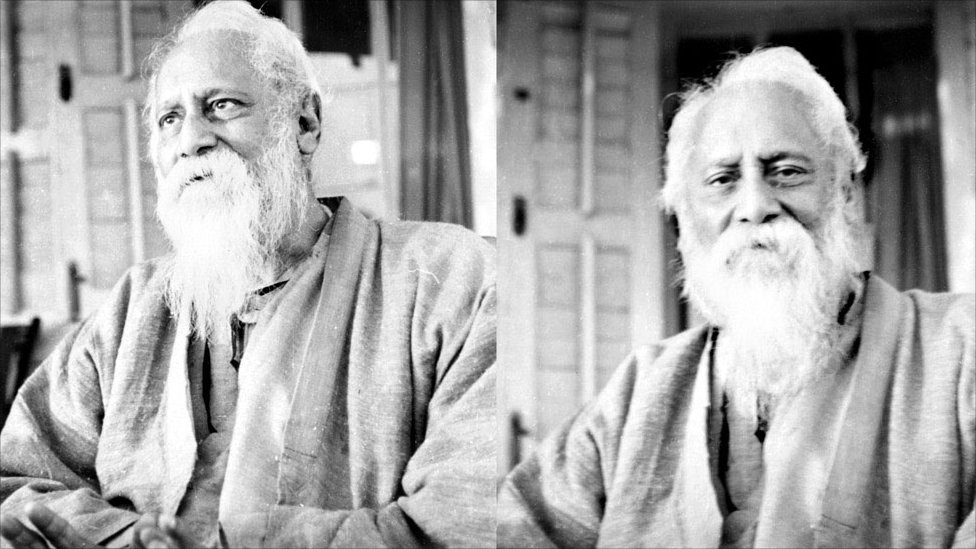

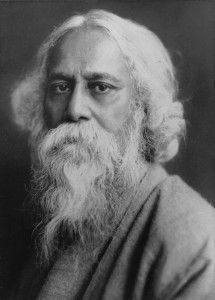

The year 2011 was the sesquicentennial of the birth of India’s distinguished polymath and Nobel Prize-winning poet Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941). The occasion was celebrated with great éclat not only in India and Bangladesh, but in cities and countries throughout the world where there are enclaves, large and small, of expatriate South Asians, especially Bengalis, and on the Internet as well. While all such celebrations noted the multiple nature of Tagore’s intellectual and artistic achievements, what biographers Krishna Dutta and Andrew Robinson term Tagore’s “myriad-minded” genius, the centerpiece of all such ceremonies was Tagore’s poetry, sung to the music either Tagore himself wrote for his 2,265 songs. Many of the lyrics for these songs were published in the poet’s own English translations in various volumes starting with Gitanjali in 1912.

The year 2011 was the sesquicentennial of the birth of India’s distinguished polymath and Nobel Prize-winning poet Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941). The occasion was celebrated with great éclat not only in India and Bangladesh, but in cities and countries throughout the world where there are enclaves, large and small, of expatriate South Asians, especially Bengalis, and on the Internet as well. While all such celebrations noted the multiple nature of Tagore’s intellectual and artistic achievements, what biographers Krishna Dutta and Andrew Robinson term Tagore’s “myriad-minded” genius, the centerpiece of all such ceremonies was Tagore’s poetry, sung to the music either Tagore himself wrote for his 2,265 songs. Many of the lyrics for these songs were published in the poet’s own English translations in various volumes starting with Gitanjali in 1912.

What many people–South Asian and otherwise–may not know is that Tagore’s poetry has a parallel existence, a western avatara, in the form of music written by many western composers who have found Tagore’s poems so engaging that these individuals made their own western musical settings of these works as well. Nearly all of these western composers have avoided writing music in the Hindustani musical style, but have used Tagore’s words and images as vehicles for their own artistic expression, creating works that attempt to capture Tagore’s sense of musicality, majesty, and mystery.

I came to know of these western compositions quite fortuitously. One day as I waited to start my lecture in my“Introduction to India” class, I noticed that one of my students, a young lady who I knew to be a vocal performance major was quietly humming as she looked at a musical score entitled “Gitanjali.” For a moment I thought to myself, rather fancifully and, as it turned out, naively: Could she possibly be singing rabindrasangit! I came to know of this musical genre during my graduate-school days years before at the University of Chicago through various lecture-demonstrations and classes given by the sublime vocalist Rajeshwari Datta (1918-76), a distinguished visiting professor there at the time who had been coached by Tagore himself on how he wanted these compositions sung. I quickly asked my student what she was doing with a copy of Gitanjali. She retorted with a smile and the kind of glee students the world over exhibit when they have found, or think they have found, their teacher in error: “No, Professor Coppola, it isn’t ‘gi-TAN-jali ,’” she replied imperiously; “it’s ‘gi-tan-JA-li!’” I asked to see the score.

To my amazement, it was a setting of six songs from Tagore’s Gitanjali composed by John Alden Carpenter (1876-1951), a Chicago-born American composer of some modest reputation. Later that afternoon I checked in my Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, at the time the most comprehensive musical encyclopedia in English, and found an entry for “Rabindranath (Sir) Tagore” with—to my amazement–cross-listings to several dozen western composers who had set Tagore’s texts to western music.

Thus began what has been a nearly four-decade research project that has fascinated me, combining my avocational passion for vocal music (both western and South Asian) with my professional passion for South Asia: uncovering the works of western composers who have set texts from South Asia to western music, with special reference to Tagore. While Tagore’s works have been, by far, the ones most often set by western composers, I have also discovered, for example, western settings of the poetry by Mahatma Gandhi’s colleague, friend, and sometimes-nemesis, Sarojini Naidu (1879-1949), as well as hymns from the Rig Veda and a chamber opera based on the Savitri episode from the Mahabharata by that most English of composers, Gustav Holst (1874-1934), who studied Sanskrit at the then newly established School of Oriental Languages, which later morphed into the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. Also notable are the operas Satyagraha (1978-79) by Philip Glass (b. 1937), based on the Bhagavad Gita, sung in Sanskrit, and recently staged at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in a spectacular production, and Haroun and the Sea of Stories, based on the novella (1990) by Salman Rushdie (b. 1947), a work of Charles Wourinen (b. 1938), which received a highly acclaimed production by the New York City Opera in 2005. Both works are highly political.

To date, I have identified over 350 western composers to have in some way used Tagore’s words—exactly, or edited, or pa

raphrased—to music. They come from widely diverse backgrounds and have used translations of the poems in their own languages, including (in alphabetic order): Czech, English, French, Greek, Italian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, and Turkish. There is some interesting symmetry in the fact that I have also discovered an Indian—a Bengali, Comolata Banerji—who has set Tagore’s English translations to western-style music and has composed western-style music to his Bengali text, and an American—Jeffrey Bauer—who has used the original Bengali in his Indian-style setting. I have also uncovered a number of non-vocal works: for example, solo piano works and incidental music composed for productions of Tagore’s The Post Office and Chitra.

Interestingly, several of the numerous women composers in the group have used men’s names in order to get their compositions published, or have used only a last name in order to get around the question of the author’s sex, which seems to have been an important consideration in the music-publishing business in the first half of the twentieth century. (Women were not supposed to be doing ‘men’s work,’ such as composing music; and if they did compose music, it would get published only rarely because it would not sell.) I have also seen several of Tagore’s poems used as hymns for Protestant liturgical services.

————————— • —————————

In a review of works dealing with the Nobel Prize-winning Indian poet, Rabindranath Tagore, the American Indologist Edward C. Dimock, Jr., states: “Immediately before the publication of the English Gitanjali in 1912, and for about two decades thereafter, Tagore flashed across the western skies like a comet. Like a comet, he disappeared. And, like a comet, he is again appearing, a little dimmed with time.”

By contrast, Tagore has always been a brilliant sun in the firmament of Indian, and more particularly Bengali, literature. Between 1913 and the mid-1930s, the brightest period of his western literary career (which he referred to as his “foreign reincarnation”), Tagore visited Europe, and both North and South America on a number of occasions, as well as other countries in Asia, notably China and Japan. These journeys to the west were undertaken in most instances as fund-raising activities on behalf of his international school, Visva-Bharati, later Visva-Bharati University. On his trips to Europe and the Americas Tagore would lecture on various literary, aesthetic, political, and social topics, and would meet the illustrious and the famous, including heads of state (viz., Herbert Hoover [1874-1964] and Benito Mussolini [1883-1945]), noted literati (viz., Romain Rolland [1866-1944] and George Bernard Shaw [1856-1950]), intellectual leaders such as Albert Einstein (1879-1955), and social reformers such as Jane Addams (1860-1835), to mention only a few.

Not only were the political, literary, and humanitarian “greats” of the world impressed with Tagore, but so were the musical greats, the yet-to-be-greats, and the not-so-greats. The tributes to Tagore by such notables as Helen Keller (1880-1968), Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945), and André Gide (1866-1951) are largely remembered today as bits of ephemera. However, the tributes of composers in the form of musical settings of Tagore’s poems live on. While Tagore’s poems are generally no longer anthologized in books of western verse (Spanish-speaking countries are the exception), his poems remain alive as western avataras in concert and recital halls wherever western music is performed.

Tagore published five major volumes of English translations of his poetry: Gitanjali (Song Offerings; 1912, 1913), The Gardener (1913), The Crescent Moon (1913), Fruit-Gathering (1916), and Love’s Gift and Crossing (1918). Preparing these volumes, he and his translators took freely from both his poetry and his songs, as well as other sources; at no point were any of his published English renderings identified as either a poem or a song in the Bengali original. Thus, what appeared as a poem in an English volume may have been either a song or a poem in the Bengali original. In some instances, such works, whether poems or songs, were once again set to music by western composers. As a result, there exists in many instances T

Tagore’s own musical setting for a piece as well as one or more by a western composer or composers. It is also interesting to note that several western composers have set the same Tagore text to music, not unlike, for example, the numerous renderings of certain famous Goethe poems, e.g., “Kenst du das Land” (Do You Know the Land), by scores of composers. Like the many musical versions of Goethe’s poems, the Tagore poems have been set by composers of varying talent, and the resulting songs range widely in artistic quality.

(The full version of the article is accessible only in print. To subscribe, please click here.)