Image credit: https://www.legacyias.com/kushiyara-river-treaty/

by Rahul M Lad 18 March 2023

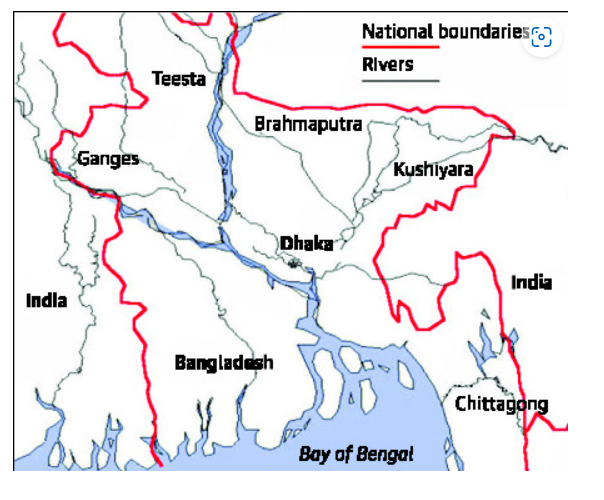

India and Bangladesh are close neighbours and share 54 rivers in between them.1 Out of these rivers, the sole river Ganga has a proper management regime in place in the form of The Ganges Waters Treaty 1996. Article IX of the treaty explicitly mentions that both India and Bangladesh are responsible to conclude a treaty/arrangement with regards to other common rivers. But, the negligible efforts from either riparian could not cut much ice. A noted water expert Ramaswamy Iyer expressed the need to develop a management regime over at least six to seven rivers. According to Iyer (1999), Sooner or later, agreements may have to be reached on at least some, say six or seven, of these rivers.2 The low-intensity disputes over the utilization of these rivers have already begun between India and Bangladesh. For instance, the proposed dam on river Barak on the Indian side at Tipaimukh has raised concerns in Bangladesh as it is likely to affect the fishing and Boro paddy production in the Sylhet division.3

Amid these uncertain environment, the major breakthrough was achieved as both the countries successfully signed a Pact over the management of shared river Kushiyara on September 2022. The first water sharing deal since the historic Ganga Waters Treaty of 1996 was signed between India and Bangladesh during Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s visit to India in September 2022. A memorandum of understanding (MoU) was signed on the distribution of water from the Kushiyara River, an outflow of the Barak River that travels through Bangladesh before entering Assam.

The Kushiyara pact assumes importance because it came into existence after a long gap of more than 25 years. The last agreement over shared water between India and Bangladesh was The Ganga Waters Treaty signed in 1996. The unnecessary silence prevailed on that front despite of overwhelming numbers of common rivers being shared by these two neighbour countries. Nonetheless, the impasse was finally broken by the implementation of an appropriate management system for the sharing of the Kushiyara river. This may usher in a new era of cooperation between India and Bangladesh on the transboundary river.

Even though the long-awaited agreement finally materialised, it may be considered a first step towards greater expectations for the management of other common rivers that are now on the waiting list.

After the Kushiyara, the attention has been shifted to one of the most awaited river i. e. Teesta. The conflict over the sharing of river Teesta could not resolved due to bunch of reasons. The Teesta River has caused conflict since the Ganges issue was resolved. Under a special deal signed in July 1983, India and Bangladesh agreed that 36% of the Teesta water would go to Bangladesh and 39% would go to India. The agreement was not, however, put into practise. Since then, there have been numerous high-level political gatherings and talks, with the most recent taking place in 2010 during the 37th ministerial meeting of the Joint Rivers Commission.

In this meeting, the two countries decided to sign an agreement on Teesta water sharing by 2011. The proposal calls for sharing 40% of the real flow at the Gazaldoba Barrage in West Bengal between India and Bangladesh and 20% of the actual flow at Gazaldoba. The formula for distributing water, however, was unsuccessful.

In 2011, draft agreement on the distribution of water from the Teesta river was produced during the visit of Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to Bangladesh, according to which India would receive 42.5 percent of the water and Bangladesh would receive 37.5 percent. For the sake of maintaining the navigability of the river, the remaining 20% of water would be set aside. This proposed arrangement, however, never materialised because of the West Bengal chief minister’s objection. The non-cooperation by the Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee might be due to the political compulsion in the state along with the reduced water flow in Teesta. But, However, Banerjee knows she cannot keep denying water to Bangladesh, a country that shares 57 rivers with India. “I support providing water to Bangladesh, but not from the Teesta, which sustains north Bengal and does not have enough water to provide to Bangladesh. Instead, I suggested to both Prime Ministers that a study be conducted to determine whether water might be provided to Bangladesh from other rivers in the area, such as Torsa, Jaldhaka, or Raidak”, she said.

From the aforementioned claim, it is clear that the Teesta is the main point of contention that may prevent India and Bangladesh from discussing their shared water resources on a bilateral basis. But, as the Chief Minister of West Bengal stated, it is important to include the management of the other rivers in order to build a cooperative environment. The Kushiyara pact must be seen as major breakthrough in this regard.

Future Path roads

It is vital to prioritise rivers because there are 54 rivers that run between Bangladesh and India. As one cannot have a management regime on all of the rivers at once, there must be some standard for classifying the rivers for shared control. The criteria may include things like how dependent the population is on the rivers, the irrigation system, the type of crops grown in the basin, the length of the river, etc. The entire river system should be divided into two or three phases based on these criteria. The rivers’ phase-wise management regime can then be developed.

The statistics on water flow for the previous 30 to 40 years is unquestionably the most important requirement to establish an agreement over shared water. The water sharing agreement between India and Bangladesh was developed for the Ganga River using historical water flow data going back 40 years. Thus, having aforementioned data is a vital prerequisite in order to get a water sharing agreement on any common river. Both the governments should take studies in this regard.

Finally, it is concluded that the momentum created by the signing of the Kushiyara Accord must be maintained. Both nations should adopt a flexible stance towards water sharing, which could create new possibilities for the administration of shared water resources. While it is clear that Teesta rivers need a water sharing agreement quickly, just like Kushiyara, both countries must take the necessary precautions to ensure that Teesta does not become a roadblock for other shared rivers.

References

- Baten, M. A., & Titumir, R. A. M. (2016). Environmental challenges of trans-boundary water resources management: the case of Bangladesh. Sustainable Water Resources Management, 2(1), 13-27.

- Iyer, R. R. (1999). Conflict-resolution: Three river treaties. Economic and Political Weekly, 1509-1518.

- Thakur, J. (2020). India-Bangladesh Trans-Boundary River Management: Understanding the Tipaimukh Dam Controversy. Observer Research Foundation, 18. Available at https://www.orfonline.org/research/india-bangladesh-trans-boundary-river-management-understanding-the-tipaimukh-dam-controversy-60419/ (Accessed on 2 December 2021).