March 18, 2020 By Shreya Paudel

To our readers: As the COVID-19 emergency unfolds around the globe, the health and safety of the communities where we work is our top priority. As we protect and care for one another, we are working hard with our partners, grantees, and staff to continue the Foundation’s important programs in Asia. We will also continue to bring you InAsia during this challenging time, knowing that readers may be more interested than ever in news of our world.

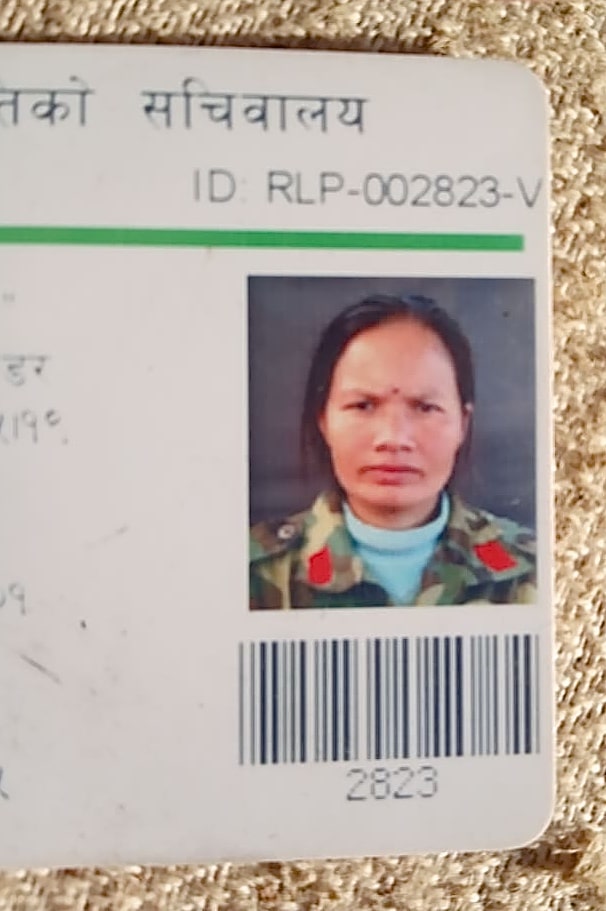

“Inequality itself is violence,” declared Tripani Bijali, speaking to a Kathmandu youth conference in January, as the auditorium of 300 young men and women erupted in applause. Tripani can speak of violence and inequality from personal experience. Swept up at age 16 into the front lines of her country’s Maoist insurgency, she is now a facilitator with a dialogue program in Nepal that aims to heal scars and divisions left by the country’s political upheavals.

Tripani was in the ninth grade at Bal Udaya Secondary School in Madichaur, Rolpa, in 1998 when the government launched operation Kilo Sera II to suppress the escalating Maoist movement. Her school was near the local police station, and police began to appear in class and take students away for interrogation. Many of Tripani’s friends disappeared into custody and were never seen again. On a Saturday morning, while she was shopping at the weekly grocery bazaar, the police came to her home and questioned her parents about her whereabouts.

“Had the police not threatened my parents, I would not have become a Maoist. It was an act of desperation,” she says of the day she fled her family home. “I became, for five years, a full-time Maoist cadre. Then, in 2003, when the party needed members from its political department to join the military wing, I was made a company commander. I have led soldiers in frontline combat.”

It was also in 2003 that Tripani married a comrade in arms. Their first child was born in 2007, a year after the Maoists agreed to join the peace process. That year, the UN Mission in Nepal verified her status as a Maoist combatant, along with 19,000 others, many hoping for integration into the Nepal Army. But the Army eventually accepted only a handful of the Maoist soldiers, and Tripani was asked to remain in the party as a civilian.

“Many of my friends found it difficult to return to society. It was like coming to a different world,” she says. This alien world, with its traditional rules and values, posed unexpected challenges for the young revolutionary couple. “When my husband and I started our relationship, we wanted to transform the world. But when we returned to society, he became a husband, and I had to become a wife. With time, I changed, but he could not transform himself, and we had to separate.”

When her second daughter turned two, in 2013, Tripani started looking for a role outside the home. She got involved in local forestry groups and finance cooperatives and started earning about $30 a month to support the family. The alien world she had reentered opened new doors for Tripani, and also motivated her to finish high school.

In 2018, The Asia Foundation’s local partner, the Nepal Peacebuilding Initiative (NPI), began looking for dialogue facilitators in Rolpa to work with individuals from different ideological backgrounds to untangle some of the region’s knotty social and political problems. The dialogue groups are meant to be a peaceful forum to work through the divisions left by Nepal’s political upheavals, including 10 years of active civil war, and to tackle new issues arising from the country’s dramatic transition to federalism. Tripani was chosen in the selection process.

At first, local officials and security forces didn’t trust her, but she has slowly and patiently built her credibility as an even-handed facilitator. The dialogue groups have helped to create a democratic space to discuss issues ranging from boundary disputes between local jurisdictions to tax issues and conflicts over natural resources. In addition to resolving conflicts, the dialogue process rebuilds relationships in the community by encouraging parties to understand one another’s point of view and promoting empathy and compassion.

In the youth group she works with, Tripani has inspired many formerly radicalized young men and women to seek political solutions within the framework of democracy. She has also encouraged women from marginalized castes and ethnicities to participate in the dialogues.

“Working with the dialogue group, leading young people and women, has made me feel connected to society again,” she says.

Tripani has also started building a house for her daughters in Rolpa. “I have a political background, and politics seeps in like a drug—you cannot escape it. But in the future I will not be directly associated with a political party. I plan to work with women and youth for their empowerment. We have seen that violence is not the answer to our biggest political problems. I believe that dialogue and peaceful means are better ways to create social change.”

Shreya Paudel is a program officer for The Asia Foundation in Nepal. He can be reached at shreya.paudel@asiafoundation.org. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author, not those of The Asia Foundation.