by Dr. Kalam Shahed 7 February 2021

Numerous great leaders have changed the historical and sociopolitical landscape in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. They include, among others, Karl Marx, Abraham Lincoln, Vladimir Lenin, Mao Mao Zedong, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, and Nelson Mandela. Additionally, there are other impressionable nationalist and populist leaders, such as Gamal Abdel Nasser, Sukarno, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Ahmed Ben Bella, Kwame Nkrumah, Robert Mugabe, Nelson Mandela, Mujibur Rahman, Saddam Hussain, Hafez al-Assad, Muammar Gaddafi, and Narendra Modi. The inclusion of Modi in this category of towering leaders may appear a historical oddity and analytically misleading. Still, he epitomizes a vibrant Hindu nationalism of over a billion people: a population that has embraced communal and religious populism over secular discourses. Lincoln, Nkrumah, Nasser, and to a lesser extent, Gandhi advocated national and regional unity for social empowerment. At the same time, other leaders struggled successfully to decolonize, seek secession, independence, and access to political powers. This commentary attempts to scan through some of the second category of nationalist leaders’ narratives: their professed political dreams and eventual delusions in claiming and realizing their dreams. This short essay is not an attempt to make an exhaustive academic survey of the political narratives, the dreams, of these leaders, as well as their successes and failures. Moreover, this discussion does not reflect on leadership in Central Asia’s ex-Soviet republics, who embraced token democracies but perpetuated authoritarian and repressive rule. The article makes a cursory survey of some notable political dreams, eventual delusions, and fallouts on the nation-states they had led.

Donald Polkinghorne termed narrative as “The primary form by which human experience is made meaningful”[1]. Narratives are deliberately designed to enable understanding of reality in a particular way. The value of narration lies in helping people comprehend their environment, their visible or perceived world, and their relation to both. Political narratives offer people easy access to relatively complex political issues by providing access to knowledge in a simplified form. Individuals’ political “common sense,” as one author argues, is shaped by not only their experience but also by the stories they read and hear on social media; or obtain from their friends and acquaintances. At some point, the audience comes to the belief that the narrated stories and experiences are indeed their own. Thus, depending on the narrative, they become instrumental in either forging changes or reinforcing, and revitalizing, the prevailing socio-political order. Therefore, the political narrative is a concept, and a device used deliberately by political strategists and their leaders to influence people’s thoughts and actions. It involves creating often imagined, and sometimes partially real, conceptions of the past, present, and a promised utopian future in contrite terms. Pan-Arabism, Jamahiriya, or People’s republic; akhand Varat, indivisible India; pan-Africanism, sonar Bangla, or golden Bengal; and Hindu rashtra, Hindu state,[2] are some popular phrases that parallel utopian-communist propaganda about the rule of the proletariat, class-free society, and borderless international socialism. In all of these cases, the narrators strived to realign with the audience’s perceptions of reality by telling multiple stories and promises.

Gandhi, Sukarno Mandela, Mugabe, Nkrumah, Nasser, Ben Bella, and Mujib were great mobilizers and used political narratives to promote their political dreams. They led their movements to fruition, curving out nation-states from the colonial and semi-colonial rule. Gandhi converted the elitist Indian Congress Party organisation into a broad-based, mass-oriented organisation. In 1921, Gandhi launched the civil disobedience movement, in which he labelled the British as alien, exploitive, and no longer desirable in India. He appealed to the audience’s Indian roots, and heritage and, thus, his meta-narrative sought self-rule in India with a promise of a better future. Muhammad Ali Jinnah expanded the narrative of “alienness” to Hindu-Muslim dichotomous social identities, seeing the need for a differentiated political destiny of his Muslim audience in British India. Nasser ignited the flame of Arab nationalism, based on distinctive historical and cultural narratives of Arabness. Furthermore, he ignored and unheeded the prevailing colonizing narratives, which were faithfully legitimized by fragmented Arab regional tribal leadership. Nasser’s meta-narrative appealed to most Arab masses, but many traditional Arab leaders continued to offer storylines along with narrower tribal and colonial discourses. Other revolutionary leaders, such as Saddam Hussain, Hafez al-Assad, and Gaddafi, who subscribed to a Pro-forma ideology of Arab nationalism and internal socialism but remained largely confined to a much narrower focus on territorial nationalism and one-person rule.

Although doctrinal Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, with the avowed proletarian revolution policy, succeeded in creating the socialist Soviet Union and communist China, these countries were, in parallel, saddled with one-party rule, with perfunctory roles for proletariat workers, marginal farmers, and landless labourers. Political reality fell glaringly short of the utopian dreams of “socialist” societies. Indeed, the one-party dictatorship had replaced the former system of “have and have-nots,” but the parties remained above scrutiny in both cases. Nestling corruption within the party hierarchy and prolonged economic stagnation obscured all other commendable social indicators of progress. Sukarno, Ben Bella Mujib, Mugabe, Mandela, and several others led to successful political mobilization with narratives for independence, economic emancipation, and democracy. Although they succeeded in freeing their nations from the colonial yoke, Western colonialism was only replaced with newly created indigenous structures: neocolonial states with façade democracies. These leaders turned the nascent democracies into one-person and one-party ruling systems.

During this period, these nationalist leaders believed in emancipation from alien power and nationalization of resources but could not overcome their inherent autocratic trends. To speak generally, aside from the rare exception of Mandela, they did not contemplate power-sharing or strengthening democracy and human rights. They viewed the newly- mobilized domestic contenders for power through the old colonial lens, considering them as inferior transgressors or belonging to an underserved group or political underclass. They made monopolistic claims to patriotism, glorifying their roles in struggles for independence, and strived to marginalize or eliminate contending socio-political elites by reshaping and reinforcing their political narratives. Nehru’s dismissive attitude towards Kashmiri demands and the need for autonomy for tribal states of Northeast India; Jinnah’s disparaging attitude to East Bengal’s language and culture; Ben Bella, Nkrumah, and Mugabe’s autocratic rule; Mujib’s disdain for the opposition and political critics, as well as his denial of a separate tribal identity for the people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, resided in those leaders’ condescending, undemocratic, and neocolonial mindsets.

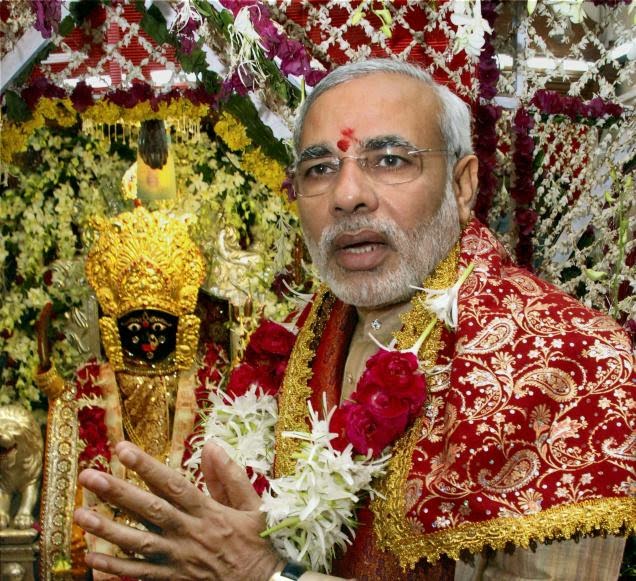

Francis Fukuyama, a political scientist, has elaborately narrated the characteristics of populist-nationalist leaders in modern democracies. A narrow, often Fascist connotation of people, based on a social class, religion, or geography, forms the core of a singular national identity. The nationalist narrative demands supreme loyalty to a nation and its components, such as race, social class, religion, tribe, and language. Populist nationalists are also experts at capitalizing on their supporters’ cultural and religious fears, ranging from fear of a loss of status in society to competing for alien socio-political forces.2 In recent times, populist leaders such as Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, and Narender Modi derived insight from Fascist propaganda to build their political narratives in their bids to strengthen radical “base”; and enable a particular political class to consolidate and claim state power. In mature democracies, such as the United States of America, this may be a fortuitous and transient phenomenon. Still, in more fragile democracies, including Brazil and India, these narratives could have a lasting impact.

In South Asia’s context, Modi’s version of Hindutva, with an accompanying neo-liberal programme, combined with a somewhat confusing policy-package of friendship and discord with smaller South Asian neighbours, creates a potently ominous pathology for South Asian societies. The prevalence of caste, class, and gender-based violence, thriving on ideological narratives that justify these social conflicts, is now increasing in India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, and to a lesser extent, in Bangladesh. More fragile democracies, such as Pakistan and Bangladesh, will inevitably be influenced by Hindutva’s meta-narratives, which have been successfully articulated and practised by Modi and his Sangh Parivar allies. With Modi at the helm of the Hindu-dominant Indian society, leaders in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal could emulate Hindutva’s popular reach and success and attempt using similar narrow and exclusionary religious ideologies to recraft their own national socio-political trajectories. Sangh Parivar’s Hindutva trappings now appear to be an enduring and expansive socio-political reality as they manifest in electoral successes: extending beyond the ideological heartland of Gujrat and Maharashtra to the states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Assam, Tripura, and West Bengal. The near-term espousal of these populist narratives would irrevocably give way to long-term delusions domestically. More importantly, they would create counter-narratives based on religious and confessional dogma in the entire South Asian region.

Modi has succeeded in dismantling the Gandhi-Nehruvian consensus of secular polity and has created enough space for a propitious growth of Hindutva. The concept of Hindutva, which envisions a society and polity based on a paradigm framed within dominant Hindu culture and identity, is not, however, Modi’s brainchild. It has a long historical growth, but Modi has been a recruit, an ardent frontline advocate, and now, the lead person to promote and implement the philosophy. His meteoric rise in Indian politics largely results from his popularizing Hindutva with a mixture of neoliberal-appealing economic programmes. As with the absolutist Taliban ideology in Afghanistan, Hindutva has become a strong and enduring religious and political force; but more than the theocratic Taliban, it provides rigour and legitimacy for successes in electoral democracy. Thus, Modi belongs to the epoch-making national leaders who have dismantled old political dreams and revitalized, if not created, an alternative. Although this rejuvenated political dream appears widely popular in India, a storm could be brewing to engulf other countries in the region. Pakistan and Bangladesh could slide irrevocably towards fundamentalist Islamic politics. Therefore, Modi’s Hindutva and its neoliberal platform could morph into a catalyst for constant regional contestation for power and legitimacy, unleashing ominous threats from polarized and antagonistic militant ideologies. Polkinghorne reminded us that citizens were mere players in meta-narratives of national and international discourse. South Asia will possibly have to pay a costly price for competing for ideological narratives, political dreams, and their delusions.

The author is a Canada-based researcher specializing in international security.

[1] Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences, Suny Press, New York, 1988

2 Francis Fukuyama , What is Populism?: Was Ist Populismus? Tempus Corporate, ein Unternehmen des Zeit Verlags, 2017