Chitralekha Zutshi, College of William & Mary

Tensions between India and Pakistan have diminished in recent days after repeated military clashes in Kashmir led to fear that the two nuclear powers could be on the verge of war.

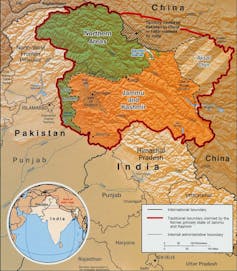

Kashmir is a disputed territory divided between India and Pakistan but claimed in its entirety by both sides.

The latest Kashmir standoff was triggered by a Feb. 14 suicide bombing by Jaish-e-Muhammad, a militant group with links to al-Qaida and founded by the Pakistan-based cleric Masood Azhar. More than 40 Indian soldiers died.

India blamed Pakistan for providing moral and material support to the terrorist organization, which is banned in Pakistan but operates openly there. On Feb. 26, India launched air strikes against Jaish-e-Muhammad’s training camps on the Pakistani side of Kashmir.

Pakistan retaliated, claiming to have shot down two Indian fighter jets on Feb. 28. Indian sources said that just one Pakistani jet and one Indian jet had been downed, and an Indian pilot taken hostage by Pakistan.

Pakistan has since released the pilot, soothing tempers – for now, at least.

Why Kashmir?

The Kashmir issue has caused tension and conflict in the Indian subcontinent since 1947, when independence from Britain created India and Pakistan as two sovereign states.

Jammu and Kashmir – the full name of the princely Himalayan state, then ruled by Maharaja Hari Singh – acceded to India in 1947, seeking military support after tribal raids from Pakistan into the state’s territory.

The two countries have fought three wars over the region since.

The first, which began in 1947, ended with the partition of Jammu and Kashmir between India and Pakistan under a 1949 United Nations-brokered ceasefire. Wars in 1965 and 1999 ended in stalemate.

But Kashmir is not simply a bilateral dispute between India and Pakistan.

As illustrated in my recent edited volume on the history of this contested territory, Kashmir is a multi-ethnic region with several internal subregions, whose inhabitants have distinct political goals.

Pakistani Kashmir consists of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, jurisdictions that want to become formal provinces of Pakistan to gain more political autonomy over their internal affairs.

Indian Kashmir includes Jammu, Ladakh and the Kashmir Valley. While the first two regions desire to remain part of India, the Muslim-majority Kashmir Valley wants independence from it.

A many-sided conflict

The desire for autonomy in different areas of Kashmir has led to repeated uprisings and independence movements.

The most prominent is a violent insurgency against Indian rule in the Kashmir Valley that began in 1989 and has continued, in ebbs and flows, over the past three decades. Thousands have been killed.

The Kashmir Valley has become a militarized zone, effectively occupied by Indian security forces. According to the United Nations, Indian soldiers have committed numerous human rights violations there, including firing on protesters and denying due process to people arrested.

The UN also cites Pakistan’s role in the violence in Kashmir. Its government supports the movement for Kashmir’s independence from India by providing moral and material support to Kashmiri militants – allegations the Pakistani government refutes. Pakistan also tacitly supports the operations in Kashmir of non-Kashmiri extremist groups like Jaish-e-Muhammad.

As a result, consecutive Indian governments have managed to write off unrest in the Kashmir Valley as a byproduct of its territorial dispute with Pakistan.

In doing so, India has avoided addressing the actual political grievances of Indian Kashmiris.

An entire generation of young Kashmiris have been raised during the 30-year insurgency. They are deeply alienated from India, research shows, and view it as an occupying power.

Militant groups in the region tap into this discontent, recruiting young people to use violence in their quest for Kashmir’s freedom. Indeed, the man who under the auspices of Jaish-e-Muhmamad blew himself up in the Feb. 14 suicide bombing of the Indian military convoy was a young Kashmiri.

Ending the conflict

Tensions in Kashmir may have subsided, but the root causes of the violence there have not.

In my assessment, the Kashmir dispute cannot be resolved bilaterally by India and Pakistan alone – even if the two countries were willing to work together to resolve their differences.

This is because the conflict has many sides: India, Pakistan, the five regions of Kashmir and numerous political organizations.

Establishing peace in the region would require both India and Pakistan to reconcile the multiple – and sometimes conflicting – aspirations of the diverse peoples of this region.

Only when local aspirations are recognized, addressed and debated alongside India and Pakistan’s nationalist and strategic goals will a durable solution emerge to one of the world’s longest-running conflicts.

Chitralekha Zutshi, Professor of History, College of William & Mary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.