When fertility rates drift from an average of about two births per woman, societies must manage population bulges of very young or old. Nigeria has a fertility rate of 5.5 children per woman, with a median age of 18. The median age for Italy, with a rate of 1.3 children per woman, is 45. Such regional differences encourage opposition to migration, especially during a coronavirus pandemic, and reproductive rights. “For many nationalists, far-right political parties and their vocal supporters, demographics have simply come down to “‘too few of us and too many of them,’ and the phrase ‘demography is destiny’ has become a powerful political sentiment sweeping across the globe,” explains demographer Joseph Chamie. Birth rates, deaths and migration are the basic building blocks of every community, and Chamie highlights how Africa’s population swells while North America, Asia and Europe represent a smaller share of the world’s population despite overall growth. As age structures change, countries respond with targeted policies: Some try paying families to bear children, and others welcome migrants. Communities with high fertility rates must provide education and create jobs. Those with low fertility rates prepare with automation, healthy lifestyles and increased pension costs. Regardless, governments must satisfy many more people. The global population is projected to reach 8 billion by 2023 and 11 billion by the end of the 21st century. – YaleGlobal

Global Population: Too Few Versus Too Many

Countries confront uneven fertility rates, bulges of young and old populations with diverse needs, along with extremism Joseph ChamieTuesday, March 31, 2020

NEW YORK: Demographics, both domestic and international, provide volatile tinder fueling social conflict, religious intolerance, racial animosity, political struggles and cultural fears – in India, Indonesia, Iraq, Israel, Italy, Iowa and more.

For many nationalists, far-right political parties and their vocal supporters, demographics have simply come down to “too few of us and too many of them,” and the phrase “demography is destiny” has become a powerful political sentiment sweeping across the globe. Authors of books such as Death of the West, You Will Not Replace Us! and The Strange Death of Europe see population trends largely determining the future of cities and entire countries. Such publications warn that the demographic changes underway challenge existing social norms, economic systems and political governance, undermining a fundamental way of life. These writers equate demographic decline to a “dying population” headed to “near extinction,” below replacement birthrates to a “perfect demographic storm” and increased immigration to an “invasion.”

The pandemic has given the extremists a “justification” for keeping migrants, refugees and asylum seekers out of the country.

Many certainly take issue with the far-right political perspective on demographics. Still, throughout human history, demographics have altered the size, composition and distribution of world populations – the result of varying rates of births, deaths and migration, the basic building blocks of every community.

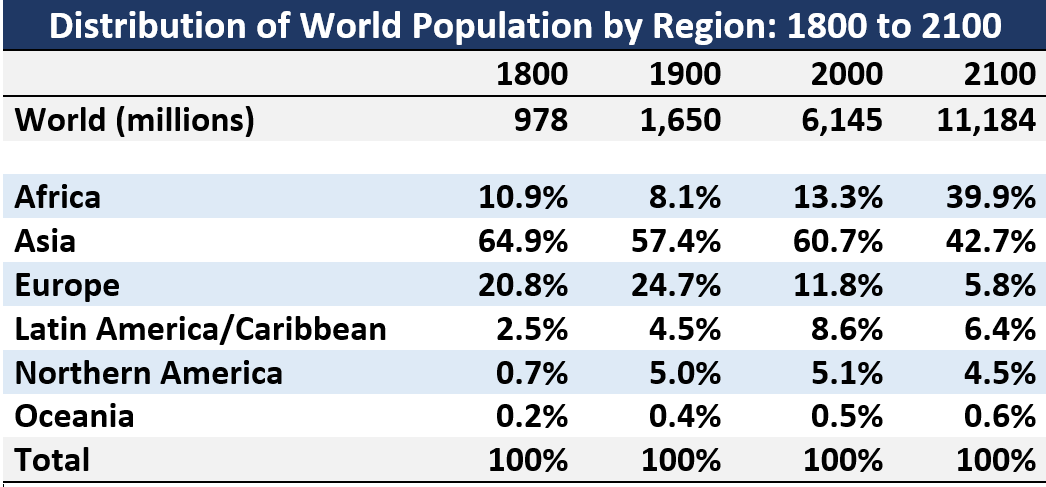

During the past two centuries, the regional composition of the world’s population has changed markedly, a consequence of differences in rates of demographic growth. Northern America, for example, increased its share of world population sevenfold from 0.7 percent in 1800 to 5 percent in 2000, largely due to immigrants and their descendants. The United States alone received an estimated 66 million legal immigrants, largely of European origin, over this period, a number many times greater than the Native American population in the country during that period. Today, immigrants represent close to 15 percent of the US population.

Similarly, the population of Oceania increased from 0.2 percent of world population in 1800 to 0.5 percent by 2000. Again, that rapid demographic growth was largely the result of immigrants and their descendants. In the case of Australia, for example, close to 8 million immigrants arrived since the middle of the 20th century, with immigrants now accounting for nearly 30 percent of the country’s population.

The relative standing of Europe’s population also changed markedly during the past century. While Europe was three times more populous than Africa in 1900, by the close of the 20th century the populations of the two continents were approximately the same size, largely due to Africa’s substantially higher birthrates. As differences in fertility rates are expected to persist throughout most of the century, Africa’s population is projected to be nearly four times as large as Europe’s by 2050 and seven times as large by 2100. Europe at the end of the 21st century is expected to represent slightly more than 5 percent of the world’s population, or about one-fifth its level at the start of the 20th century.

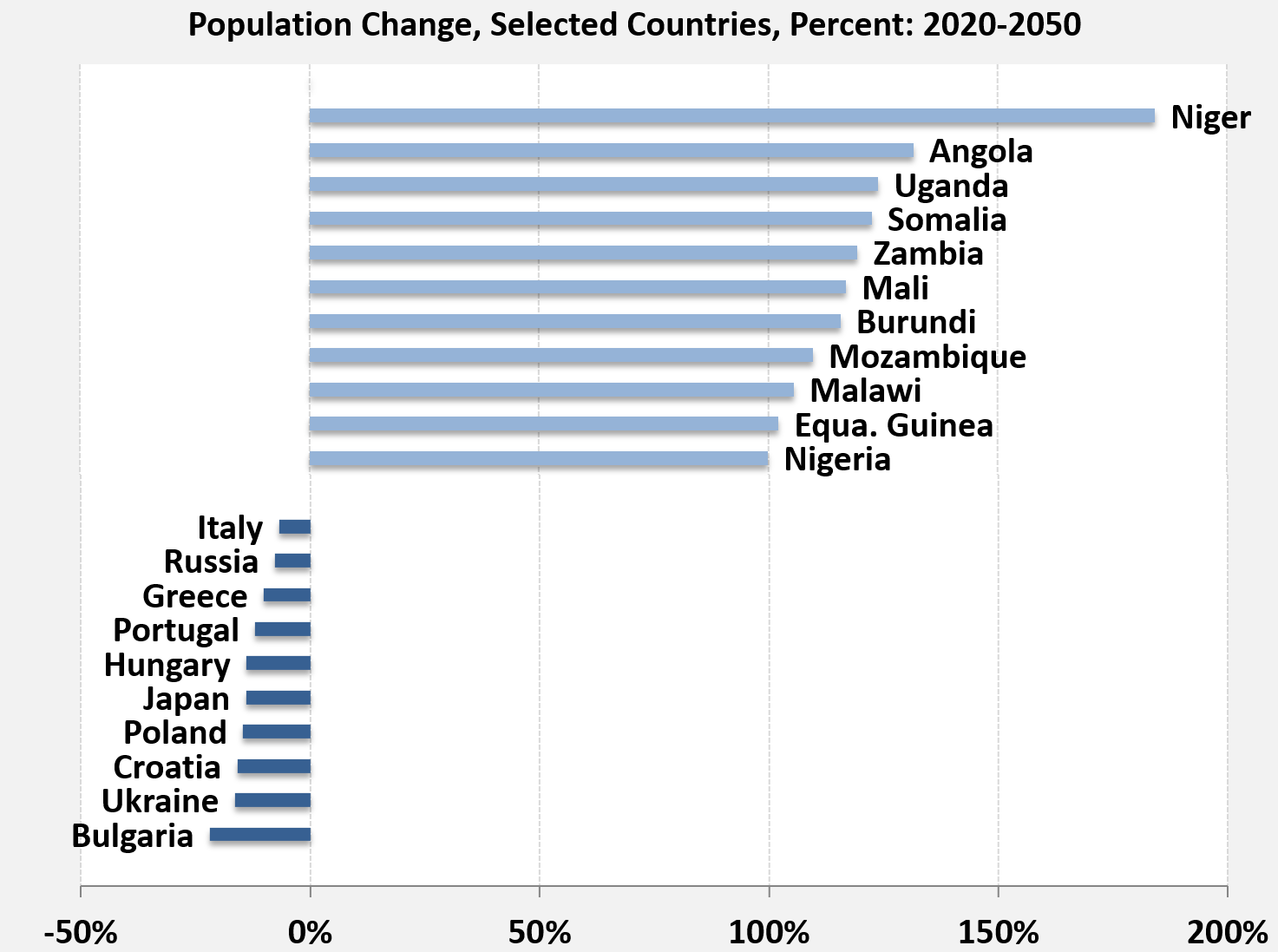

Over the next 30 years the populations of 26 developed countries, nearly all in Europe, are expected to decline by no less than 5 percent. During the same period, the populations of 16 developing countries, all in sub-Saharan Africa, are projected to more than double.

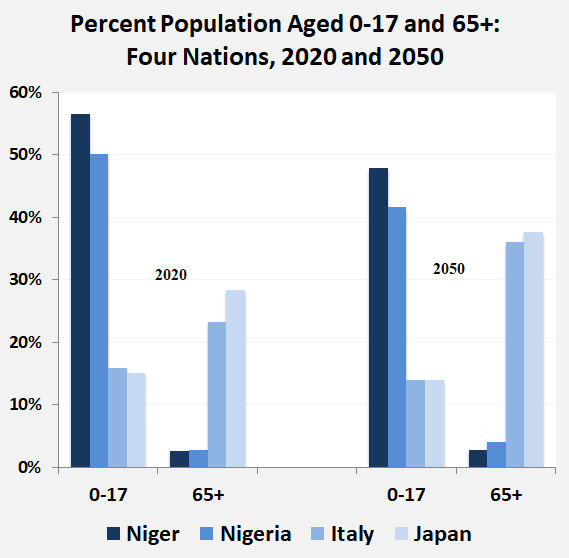

Population age structures will also shift. At one extreme are the less developed African countries – the bulk of their populations are children with few elderly. At the other extreme are wealthy developed countries with comparatively few children and considerably more elderly. In Niger and Nigeria, for example, children 17 years and younger account for more than half of the population and the elderly aged 65+ years are a few percent. In contrast, for Italy and Japan, children aged 17 and younger represent 15 percent the population and elderly make up about a quarter of the population. The age structure differences are expected to be more pronounced by mid-century, with more than one third of the Italy’s and Japan’s populations aged 65 or older.

Facing population decline and rapid aging, many countries try a variety of policies aimed at altering the course of their demographic futures. Greece offers €2,000; Japan offers 1 million yen, or about $9,400, for a fourth child; and some provinces in China consider subsidies. Such policies focus on providing incentives to encourage women to marry early and bear more children to arrest the rapid decline and aging of their country’s population.

Increasing immigration is typically not among the policy options considered to arrest population decline. Instead, in virtually every region governments have adopted policies to limit international migration – restricting levels and composition; reducing refugee flows and rejecting asylum seekers; repatriating those unlawfully resident; redefining or denying citizenship to certain groups; and most recently closing borders in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

World population is expected to reach the 8 billion mark in 2023 and 11 billion at the close of the 21st century. The distribution of that global population growth, however, is skewed, varying enormously across regions of the world. At one extreme of the world’s population growth are most of the developed countries. Largely as a result of sustained below-replacement fertility rates, these countries experience demographic decline and rapid aging of their populations.

At the other extreme are the rapidly growing, young populations of sub-Saharan Africa. These nations confront enormous development challenges and consequently are unlikely to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. In fact, many countries face difficulties simply providing the basic needs of water, food, shelter and security for their youthful and growing populations. Not satisfactorily addressing basic needs of daily life in the near term will push those countries closer to collapsing with repercussions extending beyond their borders.

Regional differences in population growth rates and age structures produce powerful push and pull forces affecting migration flows. With declining labor forces and aging populations in wealthier developed countries and growing youth populations with limited employment opportunities in poorer developing countries, enormous pressures fuel an exodus of migrants, both legal and illegal.

Without large scale immigration, which appears unlikely given current government policies and public sentiments, especially during the COVID-19 crisis, most developed countries are unlikely to raise fertility rates sufficiently to stem demographic decline and rapid aging. Governments must anticipate and plan – the advanced economies for declining, aging populations who require retirement and other social programs and the less developed economies for education and child care.

Those major trends coupled with urbanization, immigration and refugee flows give rise to increased diversity of people living side by side in dense urban agglomerations.

Growing diversity presents a major choice for governments. Communities can welcome ethnic, religious and cultural diversity as a valuable source of social, economic and cultural enrichment, economic growth and innovation, as demonstrated throughout history. Alternatively, nations can view changing demographic composition as an existential threat and resist change with intolerance, xenophobia and hostility. Growing nationalism and rise of far-right political parties suggests that many countries are gravitating toward the latter choice.

Joseph Chamie is an independent consulting demographer and a former director of the United Nations Population Division.

The article appeared in the Yaleglobalonline on 30 March 2020 and is published with permission.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published