In late February, a video featuring a man in a skull cap attacking another man started to circulate on Twitter. “You can recognize them from their clothes,” tweeted Naveen Kumar, a politician with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), in a clear reference to the attacker’s presumed religious identity. As a spokesperson for the ruling party with more than 25,000 Twitter followers, Kumar is able to reach a wide audience for his Islamophobic messaging in the majority-Hindu country.

The tweet attracted the attention of Mohammed Zubair, the co-founder of Alt News, one of India’s most reputable fact-checking organizations. Every day, Zubair sifts through the hundreds of pieces of possible misinformation that gush through India’s social media and WhatsApp channels. The video Kumar posted to his Twitter page was already going viral by the time Zubair zeroed in on it.

On March 2, Alt News published a post showing that the attacker in the video wasn’t an Indian Muslim lashing out, unprovoked, at a Hindu, as the BJP spokesperson’s post might have been read to imply, but a mentally ill man in Sri Lanka. The fact-check was uploaded on Alt News’s website, mobile app, and social media pages. Zubair also sent his findings to Kumar on Twitter. The politician didn’t delete the post.

Misinformation is a challenge globally, but in India, it’s practically baked into the ruling party’s communications. And while the platforms that are host to this misinformation, like Facebook and Twitter, have made attempts to curtail it, it hasn’t been enough to stem the tide. The average Indian media consumer is inundated with misinformation from the time they open the day’s paper to when they lie in bed scrolling on their smartphones at night, so much so that if they don’t make the effort to seek out facts for themselves, they risk responding to a fictional reality.

It’s why two engineers, Zubair, 38, and his colleague Pratik Sinha, 39, banded together in 2016 to form Alt News, which debunks false information with meticulous documentation. But while their profile has risen in recent years, they still find themselves playing whack-a-mole in a country increasingly hostile to the truth.

Alt News is based in Ahmedabad, the largest city in Gujarat. Before the pandemic forced its team to stay home, 12 full-time staffers worked out of its office, located in a quiet residential lane. Now, back home in the southern city of Bengaluru, Zubair, a charismatic extrovert, manages fact-checking assignments as well, in part, Alt News’s massive social media following — more than 1.3 million across its multiple platforms, including Zubair and Sinha’s own followings.

Every day, Zubair pores over his smartphone, scanning social media accounts that he knows exist only to pump out misinformation. He also monitors Alt News’s WhatsApp number, where people are encouraged to send images and videos. Usually, there will be requests to verify gossip about Indian movie stars, and now, as the country reels from the impact of a second Covid wave, bogus home remedies are doing the rounds.

But what makes the Indian media ecosystem unique, Zubair told me, is that much of the misinformation is focused on religious minorities, particularly Muslims, India’s largest such minority. “Typically,” he said, “it’s a Muslim doing something”: images from Egypt misrepresented as Ramadan gatherings in India at the height of the pandemic, scenes from Bangladesh misleadingly shared as anti-Hindu violence.

By 11 a.m., Zubair starts to assign stories. Some fact-checks are fairly straightforward: a reverse image search, calls with subject experts. But when the sleuthing requires more technical skills, such as when the team decides to track down the people behind a right-wing website, Zubair calls Sinha, who lives in Ahmedabad.

While Zubair manages fact-checking assignments, Sinha is the editor, and he controls everything under the hood. He helped create a mobile app that, on top of giving a rundown of the day’s fact-checks, allows users to submit material for verification, elevating them from passive recipients of the misinformation cycle to participants who actively seek out the truth.

Sinha is also the one who keeps Alt News out of trouble. India is ranked 142nd out of 180 in the World Press Freedom Index, whose creators noted in a recent report that “pressure has increased on the media to toe the Hindu nationalist government’s line.” Dozens of journalists have been charged with sedition, a crime that is punishable by life imprisonment. Some have ended up dead. Sinha manages the company’s digital security, but it’s more than just that — keeping the Alt News team physically safe is also part of his every day.

With the frequency of misinformation in today’s India, it’s easy to forget that it wasn’t always this way.

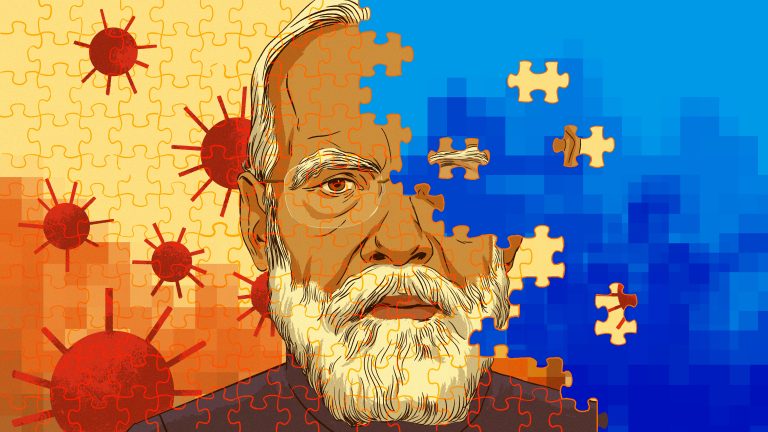

When misinformation first started circulating widely across the country, it was the run-up to the 2014 general election. The elections pitted Rahul Gandhi, the scion of Congress, the country’s oldest party, against a rising star, Narendra Modi of the BJP. At the time, the center-left Congress Party had held power for most of the nearly seven decades since India had become independent in 1947. It was known for its ambitious welfare programs, which had contributed to a steep decline in poverty. But it was controlled by a single family, the Gandhis, and dogged by corruption and complacency.

Modi, on the other hand, belonged to a low-caste family of modest means. He was known as a business-friendly Mr. Clean who had attracted major companies like Tata Motors and Ford to his native state of Gujarat. Gujarat was already one of India’s most industrialized states when Modi came to power, but members of his team had coined the term “Gujarat model,” a foundational in the myth-making of the politician’s legacy. This reputation endeared him to India’s middle class and its prosperous diaspora, who were frustrated with the country’s slow progress relative to the superpower next door, China. These groups contributed so liberally to Modi’s campaign that the 2014 election started to look like a one-horse race.

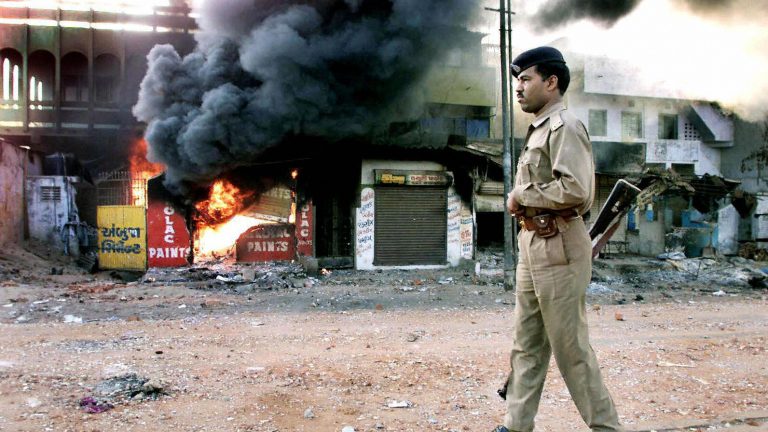

There was, however, a stain on Modi’s record. In February 2002, a few months into Modi’s first term as chief minister, a train predominantly carrying Hindu pilgrims caught on fire, killing 59 passengers. Modi claimed that the fire was an “organized terrorist attack” and decided to put the bodies on public display. His claim was supported by Gujrati-language media, which spearheaded what amounted to a hate campaign against Muslims in the region. The very next day, Hindu mobs, determined to get their revenge, set upon their Muslim neighbors, burning their homes and businesses. More than 1,000 people were killed while state police, who answered to Modi’s government, mostly stood by.

Although a Railway Protection Force report later concluded that the killings resulted from a “spontaneous altercation” between Hindus and Muslims, and a Human Rights Watch report implicated Modi’s administration in the violence, for many in India, Modi’s version of these events stuck. Nirjhari Sinha, the director of Pravda Media Foundation, the parent company of Alt News, and Pratik’s mother, calls Modi’s train story a “myth” — “one of the biggest pieces of misinformation” ever to be circulated in India.

But Modi was elected to a second term as chief minister, and then a third. By the time he was running for prime minister, two goals of his party’s nationwide misinformation campaign were evident. First, to project Modi as a capable leader by disseminating false stories of his heroism, such as the time he supposedly rescued 15,000 people stranded by a flood. And second, to project him as a global leader who would command respect for India. In one instance, a photo of the then-President Barack Obama made the rounds with the caption “Even Obama listens to the speech of NaMo [Narendra Modi].”

In advance of the 2014 elections, an army of right-wing trolls descended on Twitter. Some observers dismissed these anonymous accounts as “Modi toadies” working independently of one another. However, as a former troll would later tell the press, some were part of a large propaganda machine coordinated from within the BJP. (The former head of social media for the BJP denied this account in an interview with the Indian Express.) The opposition was ill-prepared for the charge. Rahul Gandhi didn’t get on Twitter until 2015, by which point Modi had more than 12 million followers. Today, Gandhi is still playing catch up, with 18 million followers to Modi’s 67 million. “Modi was in a position to set the narrative,” says Nirjhari Sinha, “and no one was in a position to counter it.”

The trolls mainstreamed a new language into the previously more anodyne world of Indian social media. They used hate speech and threats of sexual violence to intimidate people who expressed skepticism of Modi: opposition leaders, Bollywood celebrities, journalists, even ordinary voters.

The campaign may have left some Indians feeling like they had no option but to elect Modi; he was projected as a messiah. By then, the term “Gujarat model” was a byword for development in India.

As a native of Gujarat, Sinha had witnessed Modi’s policies firsthand. “In Gujarat, civil rights activists were telling the media that the Gujarat model was not a model of development,” Sinha said. (Critics of the model point to its hollowing out of public institutions during the period of rapid corporate development.) “It’s a model of authoritarianism, oppression of minorities, and fearmongering, and it will repeat itself.”

Modi won the 2014 election in a landslide. And anyone who thought his dalliance with misinformation was just a campaign trick was mistaken.

Alt News published its first post in February 2017, debunking a GIF that showed Donald Trump holding up a folder that read “Vote for BJP.” The viral GIF was amateurish; it was watermarked with the name of the application it was made with. But by then, it was typical of the kind of content shared by the BJP. Three years after Modi’s election victory, all Indian political parties were guilty of spreading misinformation, but only the BJP was making it integral to their entire communications strategy.

That year, Alt News showed how a slew of right-leaning websites claiming to publish “news” were actually pumping out misinformation. But Alt News does more than just address individual posts. Its team chronicles how these right-wing “news” sites are one piece of a complex jigsaw puzzle. Anything the sites posted on Facebook, Twitter, or WhatsApp would go viral in seemingly coordinated drops. Some of the websites, which appeared on Facebook groups with names like “We Support India” and “I Trust Bhartiya Janata Party,” became so popular that they had more traffic than many legitimate news sites at the time. Through its investigations, Alt News was able to uncover direct links between one of the sites and BJP party workers.

Alt News’ sleuthing led it to wonder about the core of India’s misinformation factories. One 2019 news story, about Indian airstrikes on a rural area of neighboring Pakistan during a period of heightened tension, demonstrated how primed the mainstream media had become for Modi’s brand of misinformation. While local and foreign journalists reported that the strike had likely hit a few trees, Indian cable-news channels reported that it had killed around 300 terrorists, citing “top government sources.”

The airstrikes in Pakistan came as retaliation after a terrorist attack killed 40 Indian soldiers in the contested Kashmir region, a show of force typical in the decades-long conflict with Pakistan. But in the days after the airstrike, the mother of one of the slain Indian soldiers said her family had yet to see proof that anyone in Pakistan had died. “We need to see the dead bodies of the terrorists,” she told reporters.

“Immediately after that, the images started circulating,” recalled Sinha: a set of five images allegedly showing the bodies of Pakistani terrorists killed in the airstrike. But it only took a reverse image search for Alt News to discover that four of the photos were of victims of a 2015 heat wave in Pakistan, and another appeared to be of victims of a bombing — in 2013, from a completely different part of the country.

“Someone tried to set the narrative,” said Sinha. “First, they used mass media to claim that nearly 300 people were killed, and literally every newspaper and TV channel relayed the information. Then, they filled in the missing pieces with the images and flooded everyone’s WhatsApp.” Sinha says he doesn’t believe that one person did both, but the messaging — the Islamophobic dog whistles are a real giveaway — suggests the process was organized.

Sinha’s public efforts to debunk falsities didn’t go unnoticed. In 2017, he received his first death threat via phone call: “Likhna band kar do nahin to goli maar denge”: Stop writing, or we’ll shoot you dead.

If anyone saw this dark reality for India coming, it was Pratik Sinha. He grew up in Ahmedabad, the city where Modi built his political reputation. Sinha’s parents, Mukul and Nirjhari, worked as scientists, but they were activists too. “In many of my childhood photographs, I’m sitting on someone’s lap at a demonstration,” Sinha said. His parents stood out in their business-minded family; his relatives aspired to the luxury of well-paying jobs in the West over entanglements with powerful people. In the Sinha home, the TV was set to a news channel, and at dinnertime, the conversation was all politics.

At first, Sinha chose a conventional path that endeared him to his extended family: He became a software engineer. When the Gujarat pogrom happened in 2002, he was living and working in Bengaluru. He moved to the United States, where the sort of challenges he faced couldn’t have been farther removed from the world his parents occupied; one of his projects involved digitizing grocery-store coupons.

His father Mukul, on the other hand, had lost his job because of his trade-union activities and subsequently trained as a lawyer. He was soon to become the public face of a small but powerful resistance movement. “Please don’t say this was a riot. It was genocide, pure and simple,” Mukul Sinha told The Telegraph in June 2002.

Mukul Sinha represented many of the pogrom’s victims in court. He also went on to represent the families of victims of a string of extrajudicial killings that appeared to bear the fingerprints of the state. His work was foundational to the 2010 arrest of Modi’s closest ally, a politician named Amit Shah. The day of Shah’s arrest, Nirjhari Sinha recalls, the city police commissioner’s office phoned Mukul to tell him that a mob was headed toward his house. The mob didn’t show, but such death threats were routine for Mukul. Shah was released on bail after three months in jail, and in 2019, Modi appointed him India’s home minister.

In 2013, the year before Modi’s landslide victory, Mukul Sinha was diagnosed with cancer, and his son, then 31, decided to stay home in Ahmedabad, having returned several months earlier. “That’s when my political education really began,” Sinha said. After years of being away, Sinha drew close to his family, determined to learn everything he could from his father.

Sinha was reminded of how deeply his parents had investigated the events around and following the 2002 pogrom. They were the ones who introduced him to the concept and danger of misinformation, who showed him how an entire massacre had been built on a lie. They had acquired witness testimonies and police files. His mother had personally analyzed call records that contained evidence that the state government had turned a blind eye to human rights abuses. The main lesson he learned, said Sinha, was “how to work for the cause of justice under an authoritarian regime.”

Although the Sinhas were sitting on a minefield of potentially explosive data, they couldn’t find anyone to publish it. So tech-savvy Pratik suggested that his parents publish their findings online. As his father talked, Pratik typed, putting together a dossier on Modi’s activities in Gujarat. The Sinhas’ investigations condemned the BJP leader for failing to prevent the mass murders of the riots. It made for frightening reading.

The website that resulted, Truth of Gujarat, was first published in July 2013 and quickly developed a cult following. Sinha says the mainstream media picked up some of their stories, but it wasn’t enough to create an impact at a national level. “Nowhere close.” By then, Modi’s star was already on the ascent.

Zubair, then a telecoms engineer prone to spending hours on social media, was part of the Sinha family’s growing following. To Zubair, it was apparent that Truth of Gujarat was an outlier in Indian mass media. The trend, on Facebook certainly, was barrelling in the opposite direction: A vast number of pages had mushroomed with no apparent goal other than to boost Hindu morale. Zubair, who started off thinking these were simply informative communities, soon saw that their real aim was to mobilize support for the BJP and ultimately help Modi win. “They related anything and everything to Hinduism,” he recalled.

One of their persistent claims was that everyone in the world had originally been Hindu, but that Hindus were now under threat of extinction. Zubair noticed how easily people fell for these narratives, showing their appreciation with thousands of likes on various platforms.

These “Internet Hindus,” as such content creators and their audiences came to be known, were drawn primarily to Modi, but many were also fans of a politician named Subramanian Swamy. In 2011, Swamy was removed from his teaching post at Harvard for reprehensible comments about Muslims. Afterward, he took to Twitter, where his often bizarre tweets found a huge audience. Zubair noticed that Swamy didn’t have a Facebook page, so in June 2014, in a moment of fun, he made one on the politician’s behalf.

“Did you know Mona Lisa was an Indian?” Zubair wrote on the page alongside an image of the painting photoshopped to include a sari and bindi. He posted under the handle “SuSuSwamy” (meaning, in Hindi, “PeePee” Swamy). The Mona Lisa, read the post, was actually painted by “our Hindu ancestors” and named “Mona-li Shah.”

“People believed me!” Zubair said, still incredulous. His cheeky brand of humour offered respite in an increasingly hostile online atmosphere. SuSuSwamy quickly amassed more than 50,000 followers. Before long, the real Swamy threatened to send Facebook a legal notice. Zubair affixed “unofficial” to the page and continued merrily on.

In 2015, Zubair used an infographic from Truth of Gujarat without attribution on his page. “I dropped him a not very pleasant message on Facebook,” remembered Sinha with a laugh. Zubair apologized, and the two got to talking. They discovered they had quite a few things in common: their backgrounds in tech, the fact that, despite neither of them being journalists, they had both carved out a niche in the rapidly changing world of Indian media. They loved politics. They believed in holding people accountable. And they were highly driven — each was maintaining a hugely popular web presence while also working a full-time job.

After multiple chats, the two men discovered they even shared a common vision: to leave things better than they had found them. But how?

The next year, in 2016, when work took Zubair to Ahmedabad, he sought out his new friend. Mukul Sinha had succumbed to cancer two years earlier, and Pratik had stayed by his mother’s side. Zubair, Pratik, and Nirjhari spoke of collaborating, but it wouldn’t be until the summer that their conversations led to the founding of Alt News.

After Modi was elected prime minister, Hindu mobs unleashed a spate of deadly attacks on minorities, low-caste people, and Dalits, a historically marginalized community in India. On July 11, 2016, the Gujarati city of Una became the latest to witness radical-Hindu terror when a group of men publicly flogged four Dalit cattle skinners. On August 5, Dalit groups and supporters set out on a protest march from Ahmedabad to Una, more than 300 kilometers away. Sinha and his mother went along, and he documented the 10-day long march on social media.

Despite the size of the march — several hundred people joined, by Sinha’s count — it was largely ignored in the mainstream media. But Sinha’s updates became popular and the hashtag #chalouna (“let’s go to Una”) started to trend. He realised, not for the first time, that with easily accessible technology — a smartphone and some social media accounts — he had been able to fill a hole in the media landscape and draw attention to critical issues.

Sinha’s personal struggle about whether to stay a contracted software engineer was finally resolved. He wanted to do something that really mattered.

When Sinha next saw Zubair after the rally, they came up with the idea of Alt News. Although Zubair wasn’t ready to quit his job, he was nevertheless hugely enthusiastic. Nirjhari took charge of the paperwork; the initial seed money came from savings. They were shortly afterward joined by a fourth member, who goes by “Sam Jawed” online and prefers to remain anonymous.

The impassioned group set about laying the groundwork for Alt News, its mission to counter misinformation all the more pertinent a few years into Modi’s first term. “We completely believed in the cause,” Sinha said.

While the flames of misinformation were already on the rise in 2016, one company unintentionally added fuel to the fire. That year, the Indian billionaire Mukesh Ambani launched Jio, a mobile network that offered new users free unlimited voice and 4G data for a trial period, all for the exceptionally low price of a SIM card. The offer forced rivals to drastically drop their rates, making the internet affordable and accessible to millions of Indians for the first time.

Rural India witnessed the greatest transformation, with mobile internet penetration growing at a rate of 26% in one year. In three years, there would be 227 million internet users in India’s villages. But while Indians suddenly had cheap unlimited data, many of them didn’t have the tools to differentiate between true and false online content.

The lack of computer literacy and, in some cases, literacy itself created a naïve and pliable audience. “If they got a forward from a friend or family member, they considered it the truth,” says Nirjhari Sinha. It influenced the form of misinformation that was soon to flood devices. “It’s quite rudimentary,” says Sinha. “In the U.S., misinformation involves a huge amount of story making. In India it’s two or three lines of text and an image, all tailored to WhatsApp rather than a web browser.”

By the time Jio drove down data prices in 2016, WhatsApp was already more popular in India than anywhere else in the world. One feature made it easy to weaponize information on WhatsApp: the ability to forward a single message to more than 200 people (a feature that WhatsApp subsequently removed in large part because of its role in the spread of viral misinformation). A spliced-together video, or a hoax image that would have given sophisticated internet users pause, was accepted at face value by many Indians and, with a few clicks, widely circulated. “The rise of misinformation in India is directly linked to WhatsApp,” Zubair said.

A month after Jio introduced its low-priced data packages, another major digital shift was about to take place: In November 2016, Modi took to national television to announce that the country’s largest currency bills would no longer be in circulation, starting the very next day. The move, which was introduced ostensibly to clamp down on money laundering, eliminated 86% of India’s paper currency. Indians rushed to exchange their old notes, and in the days-long melee that ensued, wild rumours circulated online: that shops were set to hike the price of essential commodities, that new notes were imprinted with a “nano GPS-chip” that would enable the government to track down money launderers.

Within a couple of years, however, such misinformation started to have more serious consequences. One persistent piece, which was still making the rounds this year, relates to the impending arrival of “baccha chors”: child kidnappers. The rumors, which often took the form of out-of-context videos, started to gain traction in the summer of 2018. They fed into old fears about a specific kind of bogeyman many Indians had grown up hearing about: a mysterious bad guy who kidnaps children to harvest their organs.

Alt News has fact-checked more than three dozen such videos and found them all to be manipulated. But the rumors have led to the murder of at least 33 people.

To Sinha, the WhatsApp rumours are the most telling example of how India’s novice internet users, particularly in the rural hinterland, are being let down by the very people who should be most concerned about what information they consume. “The government can put up billboards,” he said, “or it can get the news out on the radio, which is still very popular.” But for them, says Sinha, “stopping misinformation isn’t a priority.”

When it comes to speech on social media platforms, the Indian government’s stance is clear. In February 2021, in the midst of anti-government protests by farmers, Twitter suspended hundreds of accounts, likely at the request of the Indian government, including ones belonging to activists and journalists. Later that month, it enacted a draconian order giving it virtual control over all social media in the country. And in April, it doubled down on censorship, directing Twitter to remove tweets documenting the scale of India’s worst Covid-19 outbreak. Although the posts are visible outside the country, Twitter complied. It’s rare that the same standards are applied to accounts that regularly spread misinformation. Observers have only recently noticed the site labeling tweets by Indian politicians as misinformation.

Twitter isn’t the only Silicon Valley platform that has enabled the spread of false news in India. As far back as 2013, the link between social media and Hindu radicalization had already become apparent. In September of that year, a video most likely shot in Pakistan was misrepresented as showing Muslims killing Hindus in India, a misinterpretation that fueled a mob in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh; 49 people were killed and as many as 42,000 displaced in their wake. The next year, a Muslim was beaten to death in the city of Pune as a result of altered images circulated on Facebook. And last year, Facebook Live broadcasts drove the February anti-Muslim pogrom that took place in Delhi. “In India,” Zubair said, “Facebook doesn’t do 1% of what it should to stop hate, even when users threaten genocide.”

Although Silicon Valley platforms have often failed to address the problem of false information in India, as in much of the developing world, Sinha’s view is pragmatic: “It’s no coincidence that one of Facebook’s top people” — Shivnath Thukral, serving as an interim public policy director for India — “used to run a propaganda website for Mr. Modi. They hired him for his background, not despite it.” (A Facebook spokesperson denied this, saying, “Our recruitment process evaluates the credentials and skills of the candidate as required for a role.”) Sinha says that for a company like Facebook, connections with the BJP make business easier— or even just possible. “You can’t be in the bad books of the government.”

When Alt News first started, Sinha says, executives at Facebook would call him to talk about how to combat misinformation. It seemed like a good opportunity, a potential way to address the misinformation spread on the platform directly. But, Sinha says, it soon became clear that Facebook put money into outside fact-checking operations in order to “neutralize critical commentary.” Those who are employed by Facebook, he suggests, are less likely to scrutinize it.

In a statement to Rest of World, a Facebook spokesperson said, “Facebook is the only company to partner with over 80 fact-checking organizations around the globe, connecting people with credible information and providing context through strong warning labels, alerts and other notifications.”

Alt News never joined Facebook’s third-party fact-checking operation, and the calls dropped off.

Last November, Alt News worked on a fact-check in parallel with the fact-checking websites BOOM and the Quint, which work with Facebook, to debunk a video that was shared by a BJP leader on social media and picked up by news channels friendly to the government. The video purported to show a Muslim opposition politician being welcomed by a crowd with chants of “Long Live Pakistan,” the subtext being that a Muslim politician couldn’t help but be loyal to majority-Muslim Pakistan and therefore wasn’t to be trusted.

After the fact-check was published, Facebook flagged the video as “false information.” Three days later the flag was removed and a Facebook representative told the Indian Express newspaper that it had been applied erroneously, as politicians were exempt from the platform’s third-party fact-checking program. Emails from Alt News to communications staff at Facebook received a response pointing it to the same policy. But, that same month, Facebook had flagged a post by then-President Trump, though the post wasn’t labeled as false information outright. And, as an Alt News investigation showed, it has also flagged posts by other political figures, including leaders who belong to India’s opposition parties. A Wall Street Journal exposé published the same year highlighted instances of Facebook’s favoritism for the ruling BJP party.

The double standards may be part of the reason why the “curve of misinformation in India isn’t flattening at all,” says Sinha. When it first began, largely because of its small team, Alt News fact-checked about seven pieces of misinformation a week; they now sometimes publish that same amount in a day. On some days, they get as many as 1,000 requests for fact-checks from people on the receiving end of pictures, videos, and messages they aren’t sure are real.

And because so much misinformation in India is really just hate speech, the lack of oversight has fundamentally altered the face of social media. Certain politicians, Zubair says, publish “genocidal posts” over and over for attention. Wannabe influencers, sniffing the potential, follow suit, and the result is an online ecosystem in which people like Vikas Phatak, known as Hindustani Bhau online, have flourished. Phatak became so popular for his Islamophobic and misogynistic rants that he was invited to participate in a well-known reality TV show. The attention encouraged him to become even more vile, says Zubair. Despite this, his social media accounts were given the status symbol of a blue check.

In August 2020, Alt News became so concerned by the potential impact of Phatak’s words that it started tagging social media executives and demanding action. Their followers amplified the call, seemingly forcing the hand of Facebook and Instagram who suspended Phatak’s accounts. (He had already been removed from YouTube).

The outcome proved to Alt News what it already knew: Social media platforms respond only to pressure. It was a reminder that the ambit of their already considerable responsibilities had extended to keeping Indian social media safe. Tech companies worth many billions of dollars had in effect outsourced their responsibility to a tiny group of people.

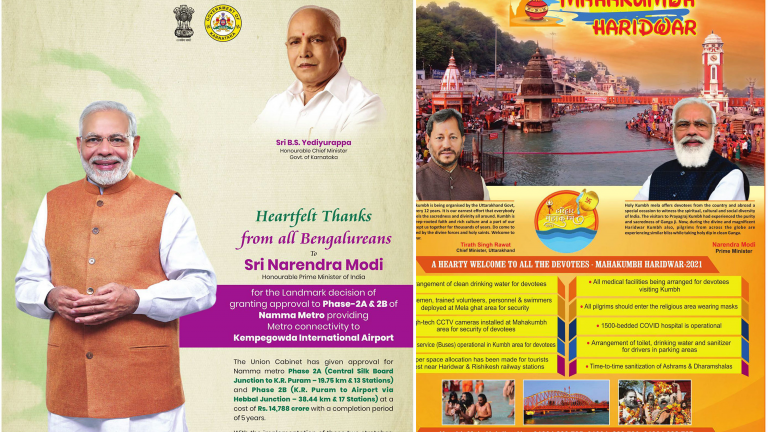

On March 21, readers of India’s major newspapers found themselves leafing through full-page ads featuring a photograph of Modi welcoming devotees to the Kumbh Mela, a Hindu festival that draws millions of pilgrims to the northern town of Haridwar. On April 22, the prime minister’s face again peered out from the front pages. This time BJP leaders were praising him for his leadership during the ongoing elections. The sheer number of ads appeared to dwarf the reports that India was on the brink of a second wave of coronavirus infections.

By the next week, Modi faced a barrage of criticism, including from experts and the international media. The papers that had run all those ads a few days prior, however, were limited in their response. The Indian Express, one of the beneficiaries of the BJP ads, published an op-ed that said that, rather than complain about the political rallies (which many now label as superspreader events that spurred the current spike in Covid-19 cases), Indians should be grateful that they live in a democracy where elections are held.

Since coming to power, the BJP government has tried to use advertising to control the Indian media. Government ads are worth millions of rupees, and many outlets rely on them to stay afloat. In 2019, the government pulled advertising from three major English newspapers, including the Times of India, in what appeared to be retaliation for critical stories. The Times lost nearly 15% of its ad revenue as a result.

The government also seems to use its proximity to major business interests as leverage. In one instance, ads for Patanjali, a company run by a billionaire yogi with close ties to Modi, were suddenly withdrawn from the Hindi news channel ABP after it ran a fact-check on a Modi quote. The Wire, an independent news website, reported that a senior BJP leader had told a group of journalists that he planned to “teach ABP News a lesson.” The loss of revenue was followed by the exit of the high-profile anchor who had reported the fact-check. (A Patanjali executive, in an email to the Wire, denied any connection between the pulling of the ads and the fact-check.) “How many TV debates do you see on the chaos in India?” says Nirjhari Sinha. “On the complete failure of the administration? Hardly any, because the government is backed by big industrialists.”

It isn’t just the fear of losing advertisements, but also the fear of tax raids, that hangs heavy over India’s media houses. Nirjhari Sinha uses the Hindi phrase “sham dham dand bhed” to describe the government’s relationship with the media: “persuade, purchase, punish, and exploit every weakness.” “That’s why people aren’t ready to speak out,” she says.

The government’s leverage means that the most objective insights on India come from operations like Alt News. The website receives financial support from The Independent and Public-Spirited Media Foundation, a grant-making group in Bengaluru. But the staff’s salaries are largely paid through fundraisers that they run most months on social media. Some of the donations are as little as 12 cents, the minimum amount allowed, but it still takes them only about two days to raise a significant portion of what they need. They boost their income with training programs and plan to publish a guide to fact-checking.

And because Alt News asks probing questions, the publication has had a real impact. Some of the websites they unmasked as right-wing misinformation have shut down. In one instance, the government had to investigate an image posted by the Home Ministry after Alt News debunked its premise. The mainstream media sometimes carries Alt News’s fact-checks, as though to compensate for its own failures.

“Zubair didn’t commit a crime. Pratik hasn’t committed a crime. They don’t need an incentive to put you in jail.”

The platform’s success has brought scrutiny. In the first couple of years of his tenure with Alt News, Zubair was doxxed by an anonymous Twitter account that circulated private photos of him with the slanderous accusation that he was a Middle Eastern plant, “funded by Arabs from Dubai,” he recalled from the post. Last year, he was the target of two criminal cases accusing him of harassment and torture of a minor. He dismissed the case as “completely bogus.” And in February, a sinister video calling for Zubair and several other journalists to be hanged circulated on Facebook, which, according to Sinha, did not act on requests from Alt News to take it down. The video also appeared on YouTube, WhatsApp, and Twitter, where a BJP leader shared it with his more than 100,000 followers.

It doesn’t escape Zubair that he’s often the main target of harassment facing Alt News. He is the most prominent Muslim face of the organization, and the prime minister’s Hindu-nationalist supporters circle him like vultures. “They could have gone after so many things,” he says. “But they chose me.” For years, he had shrugged off the abuse. But the hanging video shook Zubair. His family too, some of whom suggested that he return to the safe terrain of telecoms engineering. Zubair even, briefly, considered it, but ultimately, he stuck with Alt News. “My job is risky,” he conceded. “But it’s the need of the hour.”

Throughout our many conversations, Zubair and Pratik Sinha were careful to

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published