It is now widely recognized that the South Asia region in general and the coastal belt of the Bay of Bengal (southern parts of Bangladesh, West Bengal and Orissa) in particular, will suffer heavily in socio-economic terms from global warming. In recent years, the countries on the Bay of Bengal delta have been enjoying high to moderate growth. As a result, this region has been improving living conditions since the concluding quarter of the 20th century. While the nations of this region have been continuing to make progress in the early part of the 21st century (the global economic crisis notwithstanding), there have emerged new challenges. The most important among them is global warming and its impacts on the livelihoods of millions in the Bay of Bengal delta, particularly in the active delta parts of Bangladesh.

According to the World Bank, South Asia’s poorest of the poor are most at risk from global warming induced climate change. In particular, almost 30-40 million people of the coastal belt of the Bay of Bengal will suffer from inundation by 2050. Professor Nicolas Stern is in the view that even a moderate rise in temperature could cause serious changes to the South Asian environment.

Moreover, according to Oxford University climatologist Professor Mark New, over the past 30 years, snow cover and ice cover may have been reduced by 30 per cent in the eastern Himalayas. There is now a real risk that these glaciers might disappear altogether in the coming decades. If this happens, Bangladesh’s mighty rivers originating in the eastern parts of the Himalayas would be severely affected. The availability of fresh water would decline, and drought, as well as diminished water sources for irrigation, would become new permanent features for an ecosystem once abundant with freshwater. The Copenhagen summit (COP15) held in 2009 has found Bangladesh as one of the most vulnerable countries (MVCs) on earth with respect to climate change.

With this bleak picture in perspective, let us attempt to investigate extreme weather conditions in the Bangladesh part of the Bay of Bengal delta from 1960 to 2009. We shall examine two major areas of weather and weather related extreme conditions: rainfall and sea water surge due to cyclone and sea-level rise.

Earlier Studies

Studies on global warming induced extreme weather conditions in the Bay of Bengal delta have been previously conducted. The major findings are: Bangladesh will receive heavier rainfall during the monsoon because the rate of evaporation is expected to increase by up to 12 per cent. Mean monthly rainfall may significantly change over current variability. Monsoon rainfall may increase by 11 per cent by 2030 and 27 per cent by 2070. Over the past 100 years temperatures have increased on average by 0.50 degrees Celsius. By 2050, the mean temperature in Bangladesh is projected to rise by between 1.5 and 2.00 degree Celsius (Ahmed 2006, see also Islam and Neelim 2010). Other studies have found that high temperatures would reduce the yields of high-yielding varieties (HYVs) of rice over all seasons throughout Bangladesh. A recent study reveals that a 60 per cent moisture stress on top of other effects might cause as much as a 32 per cent decline in Boro (winter) rice yield. A quarter of the country’s landmass is currently flood prone in a normal hydrological year, which may increase to 39 per cent, and prolonged flooding can effectively reduce overall potential for HYV Aman (summer) rice production. Global warming will make tropical cyclones and tornadoes in Bangladesh stronger and more frequent. The frequency of recent cyclones, Sidr in November 2007, Aila in 2009 and Nargis in southern Myanmar in 2008 have drawn world-wide attention for the destruction they caused for lives and properties in recent years (SMRC 2007; Cline, 2009). It has been thus recognized by the international donors of Bangladesh that out of its 150 million people more than 30 million are likely to be affected directly by global warming in the next 30 years. Let us now analyze the socio-economic consequences of the two major aspects of extreme climatic conditions: rainfall and cyclonic storms (including sea-level rise).

Impact of changing Rainfall pattern

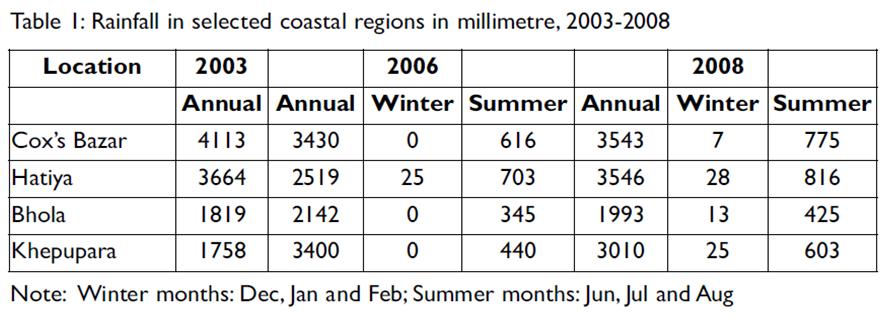

The Bay of Bengal delta is no stranger to extreme weather conditions, in terms of high precipitation, variable temperature and frequent sea water surges together with sea-level rise. The Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) combined rainfall catchment area is over 12 times larger than the size of Bangladesh, and all the rain water flushes through the Bay of Bengal delta. Table 1 presents rainfall data for various coastal districts over 2003 and 2008.

Four coastal weather stations have been chosen to investigate the climate variations. Cox’s Bazar is located on the south eastern point of the Bay, Hatiya is one of the island stations in the Bay, Bhola is also an island station located almost 50 km north (close to mainland) of the coast, Khepupara is located right on the coast. Over the 5 years covered in the Table 1, the data shows that while two centers captured increased precipitation, the rest have declined. The summer season carries the bulk of the precipitation. The rainfall in the summer (June, July and August) was one quarter of the total at Cox’s Bazar and Hatiya. This was only one-fifth at Bhola and Khepupara in 2008. The summer rain increased at all weather stations between 2006 and 2008. This increase was 23 per cent for Cox’s Bazar, 16 per cent for Hatiya, 23 per cent for Bhola and 37 per cent for Khepupara.

Historically, it is established that since the nation is located north of the Bay of Bengal/Indian Ocean and in the south of the great Himalayan Mountains, the nation is geographically vulnerable to rainfall variations. According to Mirza (2002), about 80 per cent of the total rainfall occurs during the monsoon period, in the months of June, July, August and September. The average annual rainfall of the country varies from 1200 mm in the west to 5000 mm in the east.

Cyclonic Storms and Sea-level Rise

The Bay of Bengal is known as the world’s largest delta both in length and population size. The delta is more than 700 km long and more than 40 million people live within the range of 100 km from the coast. The livelihood in this vast wet region has been based for centuries on agriculture, fisheries and small scale tourism, particularly in the south east corner (Cox’s Bazar) and south west parts (Sundarban) of Bangladesh (aid in Orissa Coast in India, as well as tourist over flow from the port city of Kolkata, that was for long the crown city of British India). The environment and the climatic conditions have been very hostile in the region, yet population density has been growing unprecedentedly compared to any other deltaic parts of the world. Cyclonic storms, hurricanes and depressions in the Bay are regular occurrences in this region.

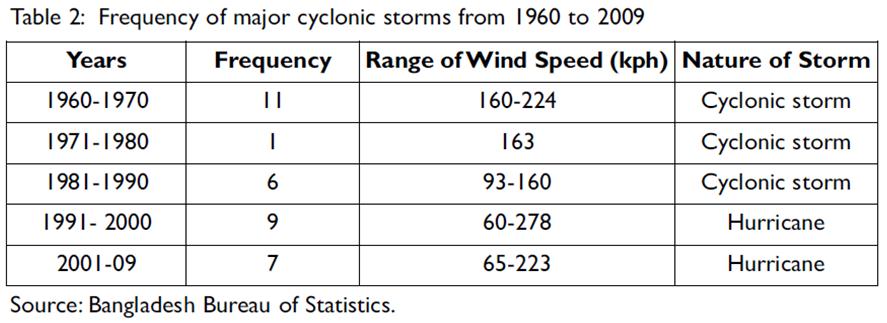

Table 2 presents a picture of the occurrence of natural disasters in deltaic Bangladesh between 1960 and 2009. On average, over the last 50 years at least one cyclonic storm or a storm with hurricane intensity has hit the coast of the Bay of Bengal every 1.5 years. Over the last five decades, the frequency of cyclonic storms has been very high, except between 1971 and 1980. The highest frequency was observed between 1960 and 1970 and the second highest was between 1991 and 2000. Due to the frequency and the strength of storms and sea water surge more than half a million lives were lost between 1960 and 1970. In the 1980s, about 100,000 people perished due to the cyclonic storms. The damage was unprecedented both in terms of loss of lives and property in the 1960s and 1970s, since the disaster management capacity and the early warning devices were almost absent during those days.

In the post-1990 period, the nation has been establishing with the support of the inter-national donors cyclone shelters on the coast and early warning systems have been put in place making use of radio and TV networks and local volunteer corps. These have kept the loss of lives within tolerable limit, however, the damage to properties, businesses and crops have increased in recent times. The population more than doubled over the last 30 years, together with new settlements taking place in newly formed islets (char land).

Most recently, rare back-to-back cyclones hit the coastal belt in 2007 and 2009. Both were rated as category 5 cyclones namely, Sidr and Aila, respectively. Sidr claimed more than 3000 lives, 9 million people were affected in 25 districts out of Bangladesh’s 64, 750,000 acres of crop land were destroyed and 175,000 acres were partly damaged. On top of these, livestock, fisheries and wild-life were the major casualties of simultaneous tidal surges.

The debate on sea-level rise in recent years has been directed mainly towards long-term impacts to 2100. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and Bangladesh-sponsored studies, in recent years, have found that the Bay of Bengal delta is highly vulnerable to sea-level rise due to ice melt in the Arctic and Antarctic, and the melting of glaciers in Greenland and the Himalayas. For South Asia, the SAARC Meteorological Research Center (SMRC)

began looking into this phenomenon in 2002 and the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Paper examined this issue in 2007. The SMRC, concluded that the sea-level along the Indian coast in and around Visakhapatnam (south-west coast of Bay of Bengal), has been rising by 0.9 mm per year between 1937 and 1991. The variations in sea-level rise between seasons appear to be higher in the Bay of Bengal coast than any other coasts of South Asia. It appears that this region has been experiencing minimal rise in the post-monsoon period. According to the IPCC (2007), however, a 10 cm rise is expected by 2030. In Bangladesh this would be sufficient to inundate 2500 sq. km, which is about 2 per cent of the total land of Bangladesh, along the 700 km long coastal belt. The IPCC’s long term prediction on the sea-level rise along the Bay of Bengal coast suggests three scenarios: rising up to 1 m, up to 2 m and up to 5 m by 2100. With a minimum 1 m rise, it is expected that all the districts located within 50-60 km of the coastal belt (of Bangladesh and India) and most of the offshore islands on the Bay would be submerged making 30-40 million people homeless by 2100.

The IPCC’s prediction has been countered by a Bangladesh-based study, which claims that the IPCC failed to consider the role of sedimentation in its prediction for sea-level rise (CEGIS, 2010). This study concludes that even if sea levels rise by a maximum of 1 m in line with the IPCC’s 2007 predictions, most of Bangladesh’s coastline will remain intact. This is due to the fact that the coastline of Bangladesh would rise with sediments originating and carried all the way from the Himalayas in the monsoon which would ultimately raise the seabed at least at a same rate of sea level rise. The sediment rise would mean that the relative sea level would be unchanged, particularly in the Bay of Bengal delta, the study claims. While the IPCC welcomes this observation, it warns that this body of scientific evidence was formed out of only a single study. Further studies are needed. The IPCC itself is expected to carry out further studies on the rate of sedimentation on the bed of the Bay of Bengal delta (and the phenomenon of Bengal Sea Fan, on sea level rise and on tsunami propensities in the Bay).

Socio-economic consequences

Climate change hazards from global warming are likely to have the following major socioeconomic consequences for the millions of Bangladeshis who live in the Bay of Bengal delta:

(a) Freshwater availability

The coastal belt of the Bay of Bengal accounts for about one-third of Bangladesh’s geographical area and over one quarter of the country’s total population. The lives and livelihoods of the coastal people are affected by such natural hazards as soil erosion, water logging, soil and water salinity, and various form of pollution. The area is prone to cyclones, storm surges and floods which are likely to be more frequent and devastating in the future as a consequence of intensifying climate change.

Bangladesh has an abundance of water on a per capita basis per year, about 9000 cubic meter. With population increase, this amount has declined from 12000 cu. m in 1990. The prediction is the amount of water availability will decline to 7,500 cu.m in 2025. Bangladesh is crisscrossed by 230 rivers, of which 57 are transboundary, 54 entering from India and 3 from Myanmar. These rivers drain more than 90 per cent of the total water generated in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) water basins annually. In the summer these rivers bust banks and cause floods every year and in the winter these rivers dry up due to lack of water flow upstream. Thus, Bangladesh’s water regime reflects too much water during the summer (rainy season) and too little during winter (lean season).

(b) Agriculture and fisheries

The food grain production trends suggest that Bangladesh, as a whole, was successful in doubling production over the last quarter of a century, keeping growth in pace with or exceeding the rate of population growth. This achievement was possible for at least three main reasons: bringing additional land under irrigation, bringing additional land under cereal production and increasing fertilizer inputs for crop-farming. Between 1992 and 2003, it is estimated that irrigated land had increased by 20.5 per cent, land under cereal cultivation increased by 5 per cent, and fertilizer use increased by 53 per cent. These achievements in agricultural extension are likely to be threatened by the extreme weather conditions in the years and decades to come. An SMRC (2007) study examined the impact on rain-fed rice yield, locally known as Aman (summer) rice, due to the variation of temperature and rainfall in recent years. This study used Bangladesh-wide data for the period 1971-1999. The rainfall data showed a negative (-0.48) correlation in August. This suggests that the excess rainfall in August caused yield reduction through physical crop damage.

A local study (Rahman and Sarker 2007) with more than 10 years tidal data (1977-98) from three collection points (Hiron point, Char Changa and Cox’s Bazar) found that the mean tidal level had been increasing in all three points. The mean tidal level at Hiron point showed an increasing trend of about 0.4 cm/year, Char Changa 0.6 cm and Cox’s Bazar 0.78 cm. An estimate suggests that salinity, water logging and acidification affect 3.05 million, 0.7 million and 0.6 million hectares of cropland of the coastal belt respectively. Most importantly, about 15-20 per cent of arable land is expected to be inundated by saline water and this would drop food grain production substantially by 2030. (Hossain et al. 2011)

The fish production trend suggests that Bangladesh, as a whole, was successful in more than doubling production between 1984 and 2006. This high growth in the country was possible for at least three main reasons: strengthening the government’s extension program on natural fish cultivation in rural areas, encouraging more and more private investment in shrimp cultivation along the coastal belt, and increased export opportunities. Exports of frozen or processed fish, of which shrimps have been the dominant items, hit more than US$500 million in 2007 (BBS 2009).

The achievements in the fisheries sector illustrated above are now under threat from sea-level rise. Finan (2009) painted a very alarming picture for the development of shrimp aquaculture in the coastal belt of the Bay of Bengal. According to Finan (2002), sea-level rise will likely result in a much larger volume of saline water moving into the canals that feed the beels (shallow water lakes), contaminating water resources and eroding gher (commercial shrimp cultivation in earthen mini-polders) embankments, which are the major sources of commercial shrimp cultivation. Another likely result of sea-level rise is saltwater intrusion affecting groundwater aquifers. This would have major adverse consequences for the groundwater irrigation system of the delta.

(c) Population displacement

Sea-level rise and its consequences for the displacement of coastal populations all over the world have been predicted by the IPCC (2007) under various scenarios up to 2100. As mentioned earlier, for the Bay of Bengal coast, the IPCC estimates the sea-level rise under three scenarios: low (up to 1 m), medium (up to 2 m), and high (up to 5 m). Taking the low scenario into account, it is expected that most of the Low Elevation Coastal Zone (LECZ) will be inundated. Any area within 10 m above average sea level is considered a LECZ. The inundation of low lying lands would create an environment which would displace millions of coastal people and push them to higher grounds. Some scholars estimate that almost a million people would be rendered homeless by 2030 under the medium scenario.

Remedies Suggested

Khan (2011) proposed a comprehensive strategy to address the challenges of climate change and global warming in South Asia called, ‘preparedness, adaptation and mitigation, (PAM). “Preparedness” measures include, but are not limited to: (i) early warning; (ii) provision for post-disaster shelter, health, water, food, credit etc. and (iii) livelihood recovery measures. Preparedness initiatives also warrant interactions among various stakeholders including the scientific community and most importantly, a decentralized governance system and community engagement process that guarantees greater accountability and ownership to the actions planned. Further studies are called for to analyze preparedness, for assessment and practice, and to discern areas of general vulnerability and micro-level differentiation. Ultimately, good studies will enhance the individual and group capacity to access governance systems both locally and nationally.

‘Adaptation’ is defined as the response to climate change in terms of organization of lives and livelihoods. It also means adapting production systems sensitive to emerging climatic conditions. In agriculture, an adaptation strategy would include changes in cropping patterns, intensity, crop location, irrigation; fertilizer, used and new infrastructure development etc. In the water resources /energy sectors, new and integrated water resource management techniques, a shift to green energy, and eco-friendly land use would be called for. Similar strategic shifts will also be necessary for health care, schooling, housing, resettlement, and internal

migration.

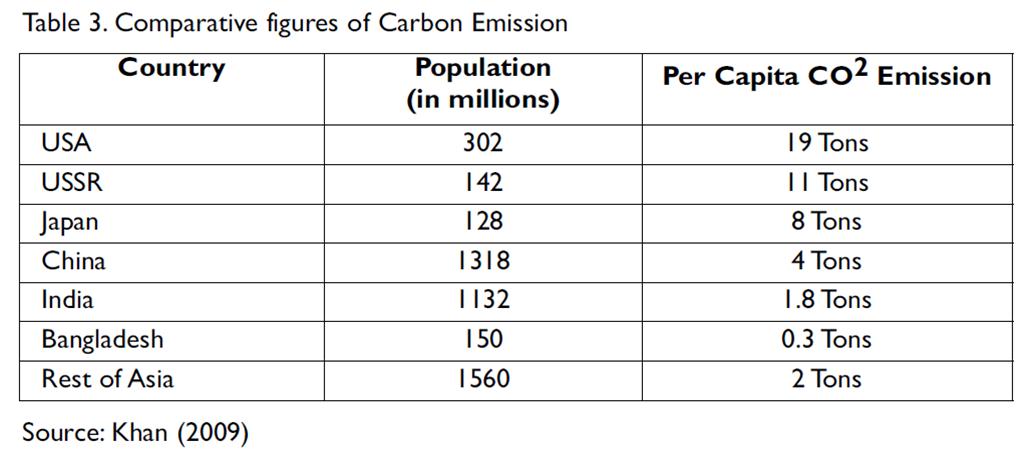

Mitigation refers to a cut on Green House Gas (GHG) emissions through the introduction of alternative and sometimes costly technological options. As the biggest GHG emitters, the industrialized developed nations are expected to bear the brunt of mitigation costs both for themselves as well as for others, especially those who lack technology. However, this has remained contentious issue.

Table 3 in the previous page presents the situation of per capita emission of CO2 of selected South Asian countries vis-à-vis the rest of the world.

Apart from negotiations for compensation from the rich polluters, the Bay of Bengal delta, one of the most vulnerable on earth to climate change, needs to seek a regional cooperation framework that promotes equitable sharing of common resources and offers freer mobility of both capital and people within the region.

A suitable in-country PAM strategy accompanied by regional cooperation has the potential to not only strengthen country interventions, but also reduce one of looming risks of climate change – potentially massive cross-border migrations and conflicts. ■

——————————————————–

Dr. Moazzem Hossain works at Griffith University, Australia. This article was drawn from his jointly edited volume, Climate Change and Growth in Asia, published by Edward Elgar, UK in 2011.

such a writing will help people a lot to be conscious about our Bengal delta.

khoob bhalo.darun.

Comments are closed.