The dragon bites its tail – Part I

16 OCTOBER 2018

FROM THE ARCHIVES: A longform piece on Bhutan’s Lhotshampa question [1992].

(This article was first published in our July-August 1992 print issue. Click here to read Part II and Part III of the article.)

Travelling east on the highway from Siliguri to Guwahati, looking north, the green of the Indian flatlands gives way to the blue hills of Bhutan. Beyond the low-lying monsoon clouds, up in the Bhutanese districts of Samchi, Chirang and Geylegphug, unfolds a story of cultures in collision.

A ruling minority feels threatened that its identity is about to be swamped by a growing majority. It decides to counter this threat by a well-planned programme of depopulation. The rulers know the world well. They are astute and use every available advantage: the remoteness of their country, manipulable media, the weakness of all outsiders for ‘last remaining Shangrilas’, and the blessings of a giant southern neighbour that obligingly turns a blind eye.

The country is Druk Yul, land of the Thunder Dragon. The guardians of the Dzongkha language and the Drukpa Kagyu traditions of west Bhutan have decided to protect their identity, and the losers are the Nepali-speakers of the south. The large-scale suffering of the southerners – Lhotshampas in Dzongkha – has yet to make a mark even in the subcontinental consciousness. The story remains largely unreported. Thimphu zealously guards its image and the little it has allowed to leak to the world media has been through the eyes of carefully vetted journalists and academics.

Many are therefore surprised to learn that Bhutan is home to communities other than the Ngalung Drukpas of the west Bhutan, and that there are Nepali-speakers in such large numbers. Coffee-table books on Bhutan ignore the Lhotshampas and tourist brochures are most perfunctory. Nepali-speakers populate large stretches of the eastern Himalaya and the attitude is – if there is a problem, “they can always go back to Nepal.” Drukpa Bhutan, in contrast, is felt to be worthy of cultural preservation for it is the last remaining Lamaist Mahayana Buddhist kingdom, a guardian of Tibetan traditions lost in the home country itself.

Bhutanese unification

In the early 1600s, when the reformist Gelugpa sect was ascendant in Tibet, monastic intrigue forced a Drukpa Kagyu monk Ngawang Namgyal to flee south through the Himalayan divide. This charismatic and strong-willed cleric, entered a rugged and beautiful land populated by aboriginals and earlier immigrants of the ‘un-reformed’ Nyingmapas. Ngawang Namgyal was a unifier; he is to Bhutan what Prithvi Narayan Shah is to Nepal. By 1639, he had defeated the Tibetans, consolidated the fiefdoms of the area and established himself as a theocrat whose spiritual and temporal rule would continue through successive reincarnations, known as the Shabdrung, into the twentieth century. The Drukpa Kagyu order, which he headed, provides the defining identity of the Kingdom of Bhutan today.

The builders of the British empire were quite willing to leave Bhutan alone as long as it made no trouble. When once in 1865 it did, the British went to war and extracted a treaty, which forced Bhutan to cede (or lease, for annual payments were made) the contiguous plains, known as the Duars. This was how Bhutan lost its tarai and today the country begins where plains meet hills.

The freedom of the Shabdrung system gave ample opportunity for the Bhutanese regional warlords, the penlops, to bicker. The British eventually decided that a centralised kingship was more in their interest. Ugen Wangchuk, fourth ancestor of the present king and penlop of Tongsa, in central Bhutan, was available and willing. It did not matter that the Mahayanic Buddhist traditions did not provide ideological support. With the agreement of the clergy and the nobility, Bhutan’s Shab drung system was packed off in December 1907. As the American political scientist and scholar of Himalayan states, Leo E. Rose, writes in The Politics of Bhutan (Cornell University Press, 1977), the monarchy came first, and the theocratic rationalisations for the Jul/Aug system were “appended” thereafter. “The Wangchuk dynasty lacked the traditional, ideological legitimation that has been so crucial to the survival of monarchies,” in Nepal and Thailand.

With the Shabdrung (at least temporarily) out of the way, the kings of Bhutan began to rule in earnest, consolidating their hold on the country while walking the fine line between the Tibetans and the British. The third king, Jigme Dorji Wangchuk, who ruled from 1952 to 1972, introduced major reforms, such as establishing a national assembly, abolishing serfdom, and beginning development programmes.

For all his sagacity, however, King Jigme Dorji was not above abetting the 1964 assassination of Jigme Palden Dorji, his friend, adviser and Prime Minister. Jigme Palden Dorji, who came from a Kalimpong-based clan of well-educated Bhutanese, had been Bhutan’s liaison with the British. He was popular, worldly wise, and a threat to a monarch who had begun thinking of his dynasty.

Nepali settlement

The southern hills of Bhutan used to be heavily forested and malarial. A Drukpa official who served there in the mid-1950s recalls that, “In those days, Drukpas were afraid to spend even one night in the south. No northerner would ever go down there, other than for brief spells during the mid-winter”.

It was the Dorji family of Kalimpong that opened these southern hills to Nepali immigration, encouraged by the British who were employing Nepalis in their tea gardens in nearby Darjeeling. The settlement and administration of southern Bhutan was carried out through a special dispensation given to the Dorji family, first by the penlops and later by the Government. They set up a system of tax collection similar to that of Nepal at the time and engaged Nepalis as collectors, such as Gajaman Gurung, who was for long a power to reckon with in the Samchi region. A prominent family of Subbas became commissioners for Chirang, and over flow from these two regions were resettled further east in Samdrup Jonkhar under the authority of J B Pradhan, who was known as Nyautibabu.

A special affinity grew between the Dorji family and the Nepali-speaking peasantry, which rarely came in contact with the penlops of the north. The Kalimpong-based Dorji rule, though feudocratic in character, was based on an understanding of ‘Nepali culture’. This was not the case with Drukpas who were to come later as administrators and representatives of the Government in Thimphu.

Though it is likely that Nepalis have continually migrated from Nepal and the Indian hills eastward into Bhutan and beyond since the 1700s, most migration probably occurred between the mid 1800s (especially immediately after the Bhutan-British war of 1864) and the 1950s. Geographer Haika Gurung believes that most of the movement was not directly from Nepal, but “step-migration” from adjacent Indian regions.

For perhaps a century, because there was minimal interaction, there was little or no conflict between the Nepali-speakers of the south and the northern population of Drukpas. The only point of contact was during the payment of annual taxes to the authorities. After the assassination of Prime Minister Dorji in 1964, Thimphu assumed direct administration of the south, assigning a special commissioner for southern Bhutan. Even under the new system, it did not seem to matter that the Nepali-speakers were different from the Drukpas. After the mid-1980s, it seemed to make all the difference.

The retired Drukpa official quoted above says, “In the old days when Bhutan was poor and needed cash, we invited the Nepalis in. The money collected from Samchi was taken to the Paro penlop. From Sarbhang, Chirang, Phuntsnoling, Tala, Kali Khola, Dagana, too, money flowed into Bhutan’s coffers.”

Recalls the official, who like all Drukpas interviewed for this article preferred to remain anonymous: “In the old days, there were strict rules prohibiting new settlements, and the system was tight because you needed data to collect taxes. Following the assassination of Jigme Palden Dorji, the Government assumed direct control, and the system became more slack. Lhotshampa landlords, particularly in Samchi did bring over illegal sharecroppers to do the labour-intensive work in the plantations, but their number was not large. And this did not happen in the inner districts like Chirang.”

Some scholars, however, believe firmly that Nepali migration is more recent. Tampas K Roy Choudhury, a history professor at North Bengal University, writes that the Nepalis posed a serious demographic challenge only after fresh immigration followed the introduction of the First Plan in 1958: “The Nepalese were mostly workers lured from Nepal or Darjeeling district by construction agents.”

The dragon turns

For a while, it did look as if Bhutan was the one place where cultures could meet without clash. Communal harmony seemed possible as the Drukpa Government appeared willing to allow southerners to share in the country’s wealth. This blunted the ever-present political desires of a more-educated Lhotshampa population. According to Rose, the “comparatively liberal approach” towards Nepali-speakers in the 1950s and 1960s “tended to make Nepali Bhutanese unresponsive to suggestions that political organisations and agitations were required to attain community or regional objectives”.

Nepali-speakers were allowed to rise up the ranks in the bureaucracy. They demanded and received citizenship in 1958, and marriage between Nepalis and Drukpas were encouraged with cash incentives. The signboards were in Dzongkha, English and Nepali, and all three were taught in schools. In 1980, the Nepali festival of Dasain was declared a national holiday. The King granted Dasain Tika to Nepali-speakers, who willingly wore the Bhutanese national dress olgho and kira on official occasions. The King proposed the construction of a Hindu temple in Thimphu, and encouraged the absorption of more Nepalis into the army and police.

As a memorandum presented in July to members of the Indian Parliament by refugee leaders states, “the forces of economics, politics and social sciences were already tying together, irrespective of ethnic lineages, all Bhutanese people through common interest and common destiny.” The idyll was shattered in the mid-1980s. A fuse lit in 1958, when the country began its drive for economic modernisation, eventually reached the powder keg. “Until the early 1980s the different ethnic groups in Bhutan were living in a happy atmosphere of brotherhood. But as 1985 gave way to 1986, and the Sixth Five Year Plan of Bhutan was unfolded, almost overnight the Government started to maltreat the southern Bhutanese,” says D N S Dhaka, an engineer and economist who is now General Secretary of the Bhutan National Democratic Party (BNDP) in exile. The King declared that the preservation of tradition and culture was a priority of the Plan. The Lhotshampas’ downfall had begun.

The Lhotshampas were actually the second community to have a falling out with the Drukpa elites. In 1974, the Government had cracked down harshly on Tibetan refugees in Bhutan, ostensibly for conniving with the late King Jigme Dorji’s Tibetan spouse Yanki, to wrest the throne for her son. There was persecution, jailings, in any reported deaths; the Tibetans were given the choice to either become Bhutanese citizens or “follow the Dalai Lama” and leave the country.

There had always been a certain ambiguity in Bhutan’s endeavour to catch up with the world. The elites, earnest modernisers educated in Darjeeling public schools, were extending their control over a land steeped in Umaist culture. At some point, however, modernisation was bound to come up against the traditionalists’ world view and the modernisers’ own economic self-interest. When that time arrived, inevitably, the rulers decided that Nepali-speakers threatened not only Bhutan’s socioeconomic and political status quo, but their culture, too. Ambiguity gave way to Drukpa chauvinism, spearheaded by single-minded bureaucrats who had a green signal from the King.

As educated Drukpas returned from the Indian schools and needed employment slots, the Lhotshampas were marginalised. Nepali signboards were painted over and the language banished from the classrooms of the south. Senior Nepali civil servants, those that still remain in the civil service, are now cowed and pushed aside. D K Chhetri, Joint Secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and former Ambassador to Bangladesh, for example, was ousted from the presitigious Foreign Ministry and made Secretary-General of the Bhutan Olympic Committee. The Foreign Minister Dawa Tshering apparently told him to step aside as “the situation is not right at the moment”. Says a friend of Chhetri’s, now a refugee,”At least he got to go to the Barcelona Olympics.”

In early August 1992, Hari Chhetri, Second-Secretary in the Embassy in Kuwait and the penultimate Lhotshampa in the Foreign Service, defected straight to exile in Kathmandu rather than return and await marginalisation.

Fear of engulfment

The present monarch. King Jigme Singye Wangchuk told the Reuters news agency in February that Bhutan is facing “the greatest threat to its survival since the seventh century.” Which was when, according to legend, Guru Padma Sambhava brought Buddhism to Bhutan, flying in from Tibet on the back of a tiger. The Drukpa ‘nation’ was established much later, in the 17th century.

Towards the beginning of the Sixth Five Year Plan (1987-1992), it appeared that the main danger to Drukpa culture was modernisation through exposure to the outside world. Television antennae were dismantled, tourism curtailed, and the Drig Lam Namzha code of cultural correctness implemented. Before long, and as the Lhotshampas reacted to-the code’s strict implementation, the enemy became not modernisation but the Nepali-speakers of the south.

King Jigme and his senior officials all use the term “endangered species” to describe Drukpas, and point constantly to Sikkim, where a Nepali majority curtailed the rule of the Chhogyalin 1973.

In January, Foreign Minister Tshering told the Calcutta Statesman, that if the “influx” of illegal immigrants continued, in another two decades Bhutan would be turned into “another Sikkim and Darjeeling”. King Jigme told the Reuters correspondent that “in the next 10, 15 or 20 years… Bhutan will no longer be a Bhutanese nation. It will be a Nepali state… just like Sikkim.”

Southern Bhutan attracted Nepalis, he said, because of its free education, free health services, higher wages, and the availability of good land for cash crops and cereals.

The refugee leaders in the camps of Jhapa, meanwhile, are incredulous that the King, his officials and gullible foreign diplomats continue to speak of an “influx” into Bhutan when there has been an “exodus” these past couple of years and whatever loopholes existed for illegal immigration were firmly sealed in early 1988.

The northerners’ fear of being swamped by the Lhotshampas is real, however. When the rallies spearheaded by the Bhutan People’s Party (BPP) shook the southern districts in September and October of 1990, Thimphu residents waited in dread for Lhotshampas who they thought would at any moment be marching up the highway from Phuntsholing. But are there grounds for such fear or is it paranoia?

A pamphlet prepared by political exiles in early-1988 finds the very ideal of a cultural threat laughable: “Someone learned in cultural anthropology must tell the administration that culture lives or dies by its strengths or weakness. Is Drukpa culture so fragile that it will collapse in the presence of Nepali culture? Such a fragile culture is not worth preserving.”

The pamphlet goes on, “Once Chhogyal Raja of Sikkim ruled his country in a [brutal and uncivilised] way but that consequently led the country to become an Indian state. And at present the Drukpa rulers are marching the Chhogyal way.” Such language could hardly have helped instill confidence in Thimphu’s Samtheling Royal Palace.

North Bengal University’s Roy Choudhury takes Drukpa fears more seriously. “In the last decade ethnic problems in neighbouring Sikkim and West Bengal have caused great consternation in Bhutan. Gorkha militancy in Darjeeling arose further Bhutani suspicions about Nepali settlers. They could hardly ignore the fact that the Nepalis had gradually wiped out the Lepcha and Bhutiya communities as political elements in Sikkim.”

Whatever its basis, the cultural anxiety of the Drukpashas expressed itself in an unfortunate programme of depopulation. But does cultural anxiety alone explain the Government’s heartlessness towards the Lhotshampas? What else accounts for the obvious insensitivity of the dzongdas and dungpas (District Administrators and sub-divisional officers) as they chase the Lhotshampas from the southern hills?

Despite the bluster of the pamphlet and intermittent militancy along the southern border, the Lhotshampas’ assertion of cultural identity as ‘Nepalis’ hardly posed a challenge to the political order. Indeed, it is plausible that Nepali-speakers saw the economic advantage of remaining ‘Bhutanese’ and might have lived within Drukpa strictures – as long as the regulations did not violate their deeper cultural identity of being a Bahun, a Tamang or a Rai.

There is no indication that the Nepali-speakers were, as of 1988, organising to topple the crown or invade the north. Nor does it seem probable that anyone was seriously contemplating asking India’s help to ‘do a Sikkim’ on Bhutan. It is more likely that, as the Nepali-speakers became politicised against the 1988 census exercise and implementation of the Drig Lam Namzha code, the Thimphu decision-makers decided to nip the ‘Lhotshampa problem’ before it even budded.

Lhotshampa allegiance

Excerpt from a Kuensel report of 30 May 1992, “While many of the people felt that it was good riddance that some of the Lhotshampas were leaving the country, others felt that there might be a sinister motive for these people to leave without anyone forcing them to do so. ‘I believe that these people are leaving with the sole objective of slandering the government by claiming that they are being thrown out,’ said Tshongpa Tshela, the president of the Tongsa business community.”

“One Nation, One People” became the rallying slogan of the Government. “Because Bhutan is small, it cannot afford to have too many divided identities.” And the Ngalung Drukpa culture would provide the single identity to the populace.

For the Drukpa official searching for clues, there were probably enough to reveal where Lhotshampa loyalties lay. When the Drig Lam Namzha cultural code was implemented, for example, some Lhotshampa students at the Teacher Training Center in Paro might belt out Sri Maan Gambhir, the national an them of Nepal, to taunt the Drukpa students. Even after King Jigme started his own Dasain tika ceremony, Lhotshampas still waited for Radio Nepal to announce King Birendra’s tika before starling their own ceremonies. When a village mandal or headman, would be over-strict with Drig Lam Namzha, youths would discard their gho in defiance and don the Nepali labeda surwal.

To the Drukpa, this was a clear case of rebellion against the Tsa-Wa-Tsum, the King, the Kingdom and the Government (the three elements of Bhutan). But refugee leaders insist that by such acts the Lhotshampas are emphasising their cultural identity and not their political allegiance. “Bhutanese Nepalis, when they wait for the Nepali king’s tika indicate their Nepali cultural roots. There is nothing political in this,” says R B Basnet, President of BNDP.

How Bhutanese the Nepali-speakers of Bhutan are depends on how you define’Bhutanese’. If asked to choose between being Drukpa Bhutanese and Nepali-speaking Bhutanese, the Lhotshampas would overwhelmingly opt for the latter. `Nepali culture’ implies a mix of many ethnicities, some of them subsumed under a generic Nepaliness, others retaining distinct tribal and caste identities. But the enforcement of a Drukpa identity affects equally the Newar, the Kirat, the Tamang or the Bahun/Chhetri.

For a while Drukpa administrators appear to have toyed with the idea of divide and rule – during the census exercise in the south, for example, some dungpas tried to encourage the perception that the Bahun/Chhetri were monopolising leadership among the Lhotshampas.

Ratan Gazmere – an Amnesty International “Prisoner of Conscience” who was released in December 1991 – recalls Sangey Thinley, an officer of the Royal Bodyguards advising him in prison, “Bhai, this movement is in the interests of the Bahuns and Chhetris and you will soon be sidelined.” Says Gazmere, now in exile in Jhapa,”There is certainly an attempt to divide Nepalis, but it will not work because the oppression and evictions are cross-ethnic.”

Indeed, the refugee rolls, lists of torture victims and other such information indicate that the suffering runs across caste, ethnicity and gender. One list of death in police custody reads: Chhetri, Sharma, Gurung, Limbu, Rai, Kami, Karki, Adhikari and Pokhrel. Another list of rape victims reads Luitel, Gurung, Rai, Sherpa, Chhetri, Basnet, Guragain, Thukpawalni, Gotame, Sunar, Magarni, Kharel and Niroula. The leadership in exile includes Basnet, Budathofci, Chhetri, Dhakal, Gazmere, Pradhan, Rai, Sharma and Subba.

Bhampa Rai, a doctor who as General Secretary of the Human Rights Organisation of Bhutan (HUROB) heads the refugees’ effort to organise themselves in the camps of Jhapa, agrees that, like elsewhere in the Nepali-speaking diaspora, there are ethnic disparities among Lhotshampas. “But that is for us to sort out once we get back to Bhutan. The Government is mistaken if it thinks it can divide us in opposition.”

While Lhotshampa allegiance to Thimphu’s political authority was still unquestioned, by mid-1988 the King and his coterie knew full well the feeling towards Drukpa-flavoured Bhutanisation. Cultural indoctrination, mildly pursued, might have been acceptable to Lhotshampas who saw clear advantages in health care, education, employment and economic well-being which Bhutanese citizenship, rather than Indian or Nepali citizenship, afforded them. In time the Nepali-speakers would feel fully ‘Bhutanese’, as the Drig Lam Namzha desired. Lhotshampas would begin to acquire Drukpa cultural traits and, in fact, they appear to have been willing to go that distance. But the implementation of a rigid policy by zealous administrators and army and the police officers seems to have been unbearable.

***

~Kanak Mani Dixit is founding editor of Himal Southasian.

This article was first published in our July-August 1992 print issue. Click here to read Part II and Part III of the article.

The dragon bites its tail – Part II

17 OCTOBER 2018

FROM THE ARCHIVES: A longform piece on Bhutan’s Lhotshampa question [1992].

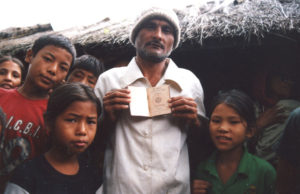

A Lotshampa refugee at a camp in Jhapa District of eastern Nepal showing his Bhutanese passport.

Photo: Alemaugil / Wikimedia Commons

(This article was first published in our July-August 1992 print issue. Also read Part I and Part III of the reportage.)

No more a backwater

Bhutan was still an economic backwater at the end of the 1940s. The economic, cultural and social interaction and sustenance was almost exclusively with the north. The forested southern hills, the malarial jungles of the Duars and, beyond, the India of the British Empire, held little charm to the pastoralists of high valleys.

As Rose writes in The Politics of Bhutan, Nepal had “pervasive cultural, economic and political ties to the South, whereas Bhutan (was) a Buddhist society in which traditional ties, at least until 1960, had been to the north.” All that changed with the Chinese takeover of Tibet in 1959. Overnight, there was a historical shift as Bhutan’s external and economic relations spun 180 degrees to realign with India.

With this reorientation, the value of the southern hills to the Drukpa rulers was also to change. In the traditional economy, this region had no role other than as a source of modest revenue, that too as the Nepali settlements grew in the last century. Over the 1970s, however, it became clear that the south was not only of strategic importance as the gateway to India, but also in itself a storehouse of riches for the modem economy. It was the southern districts that had the cardamom plantations, orange groves, ginger crop, minerals, and hardwood forests. Even the rivers whose source was the Himalayan snows had to traverse to the south before their flows were substantial enough to be tapped by hydropower projects. All major industries had to be based in the south, close to raw materials and to the plains market. The north, the fountainhead of Drukpa culture and identity, had two resources: conifer timber and tourism, with the possibilities of the latter held in check by a cautious clergy.

The realisation that the south had become a potential economic powerhouse must explain in part why the Drukpa elite turned against the Lhotshampas. The Chukha Hydropower Corporation is a case in point. Inaugurated in 1938, the plant suddenly started injecting huge amounts into the national exchequer. Any social scientists (there are few in Bhutan, though) could have predicted social and political repercussions from Chukha.

Says Dipak Gyawali, a Nepali water economist who has studied the societal impact of large dams, “Mega projects bring mega dislocations to society. Those who control the distribution of the additional revenue have the power to destroy social exchange mechanisms and economic balance.”

The Chukha bonanza, which started accruing in 1988 clearly provided Thimphu with the self-confidence to move ahead with its plans for the south. Chukha, perhaps, showed the rulers the riches that lay within their grasp but for the Nepali speakers of south who had the potential of agitating for their share.

A Thimphu ashi (princess) who back in the late 1960s used to arrive at her Darjeeling school in a battered, dusty Mahindra and Mahindra jeep today drives around in a late model air-conditioned Mercedes. What would she do or not do to ensure that she does not end up back in the jeep?”

King and Tshongdu

The present King’s father, Jigme Dorji Wangchuk, made the reforms which brought Bhutan part of the way into the present century. He set up the Tshongdu, or National Assembly, initiated a cabinet system of government and made the monarch accountable to the Tshongdu. The Tshongdu became more powerful in 1968 after King Jigme Dorji surrendered his right to veto bills. The following year, again upon his insistence, it was decided that a reigning monarch could be impeached if two-thirds of the Assembly supported a vote of no-confidence.

But regardless of these innovations, Bhutan’s political and legal system remained ‘primitive’. Fundamental freedoms – of expression, speech, press, religion, association – are absent. To organise political rallies is considered ‘anti-national’. Arrest can be arbitrary, long-term imprisonment without trial is kosher, and there is no doubt remaining of the systematic use of torture and extra-judicial punishment. Any action against the Tsa-Wa-Sum is, as approved by the Tshongdu in March 1990, treasonable and punishable by death under the Thrimsung Chhenpo legal code.

Presently, public trials are being held of 41 “ngolops”, or “anti-nationals”, the most prominent among them being D K Rai, an electrical engineer and former Secretary-General of the Bhutan People’s Party (BPP). The trial, being played out in the square before the High Court in Thimphu, is for “anti-national” activities.

According to the Student’s Union of Bhutan (SUB), an exile opposition group that was begun underground in Sherbutse College in central Bhutan, proceedings before the “farcical court” are being used to dupe the world into believing that a “judiciary” exists in the country, “while hundreds [of] others still languish in jails without trial.” SUB also claims that royal pardons and amnesties granted to so-called ngolops are orchestrations to gain international sympathy. “Prisoners are released prior to events like the Colombo SAARC summit, and the Amnesty Team visit.”

Today’s Tshongdu is a conservative body that is, even more than King Jigme, the propagator of Drukpa culture for all of Bhutan. The Tshongdu articulates the sensitivities of the monastic order, the top-level bureaucracy and the feudocracy that together rule the country. A breakdown of the present Tshongdu shows that 77 (51 per cent) of the members are Ngalungs, 58 (38 per cent) are Sarchops and 16 (11) per cent are Lnotshampas.

The most inflammatory, and at times even racist, pronouncements relating to the Lhotshampas have come from the members of the Tshongdu. They vocalise sentiments that sophisticates like Foreign Minister Dawa Tshering would never let escape their lips. “As Lhotshampas have proved themselves untrustworthy, ail Lhotshampas in government service should be retired,” says one Assembly member. According to another, Karma Tshering from Tshangkha, “We hope that these ngolops will be given capital punishment and publicly executed.”

To what extent is the Tshongdu a parliament which incorporates principles of popular participation? A C Sinha, a professor of sociology who has just published the book Bhutan: Ethnic Identity and National Dilemma (Reliance, 1991), says the Assembly is made up of “the traditional ethnic chiefs or village headmen from the hills or the pliable, loyal and faithful subjects of southern Bhutan.” Sinha says the Tshongdu lacks the ability to provide the Government with “critical and frank review of its performance.”

King Jigme, as chief executive, sometimes appears to be using the Tshongdu’s avowed conservatism as a battering ram for his Government’s policies. Reports in the government-owned Kuensel weekly paint the picture of a bellicose Tshongdu membership being pulled back from the drastic action against the Lhotshampas by a benevolent King Jigme. It is difficult to say how much of this tussle is genuine and how much it is a charade.

Back in the 1960s, the present King’s father had to battle it out with the Tshongdu before he could force through his programme of modernisation. Once, King Jigme Dorji was even forced to point out that all of Bhutan’s heritage did not deserve preservation and that the imposition of certain Drukpa rules and regulations would cause unnecessary hardship to minorities – the Nepali-speaking Bhutanese and the Tibetan refugee settlers who had distinct cultural traditions of their own.

The present King had his own row with the Tshongdu during its October 1991 session, “one of the most emotion-charged National Assembly sessions the kingdom had ever seen,” according to Kuensel. After passing resolutions on all aspects of the “anti-national problem in southern Bhutan,” including the “extradition of ngolops”, “identification of ngolops and their collaborators,” “withdrawal of citizenship identity cards” and “implementation of the Citizenship Act”, the Speaker took note of the almost total unanimity of opinion among the members to stop development activities in the southern districts.

At that point, King Jigme intervened and reminded the members that they had already entrusted him with the responsibility of finding a permanent solution to the ngolopproblem. If the authority and power to decide on how to go about finding a solution to the problem was not in eluded with the responsibility and accountability involved, it would be impossible to find a proper solution to the ngolop problem. The King then pledged to abdicate if he did not succeed in finding a lasting solution.

After the King’s outburst, the members “requested his kind indulgence and understanding” and pledged their complete loyalty, support and confidence in him. The Tshongdu resolved that the responsibility of finding a permanent solution to the ngolop problem should be entrusted entirely to the King along with all the prerogatives and powers as would be deemed necessary.

King Jigme was born on 11 November 1955 and became the fourth King of Bhutan in 1972 at the age of 17. His reign has seen increasing centralisation of power in the Royal Palace. The ability of the Tshongdu to impeach the monarch was abolished in 1973.

Some of the King’s critics in exile maintain that in part the problem in southern Bhutan has its origins in his matrimonial links. In October 1988, King Jigme formalised his marriage with four sisters, the daughters of an ambitious businessman from Talo in Punakha District. According to BNDP’ss Dhakal, “a mistake in private life” (i.e. the royal marriages) might have led to the change in King Jigme’s attitude towards the Lhotshampas. “The King was forced to make a political pact with the traditionalists. In exchange for legalising his marriages, the King would implement a Bhutanisation programme and a set of schemes to reduce the population of Bhutanese Nepalese.”

King Jigme is said to be simple, matter-of-fact, and unostentatious. He lives, mostly with his senior queen Dorji Wangmo, in a log-cabin palace near Tashichho Dzong complex, which houses the Secretariat and the Tshongdu. The monarch is well-liked by both diplomats and foreign journalists, who jump to give him the benefit of the doubt. According to Indian journalist Narendra Kumar, writing in the Calcutta Statesman, the King is “handsome like a Greek God, is courteous to a fault, publicity-shy, a teetotaller.”

Says a Western Ambassador to Thimphu, “The King is very austere, very dedicated to the cause of the people… when they say that people have access to him, it is true. It is quite different from the Nepali monarchy during the Panchayat years.”

Before the troubles began, King Jigme was much liked by the Lhotshampa population as well, probably in the belief that his liberalism would save them from the conservatism that lurked just below the Druk Yul’s calm surface. “This was a hard-working king who was really in touch with development works around the country,” recalls Om Dhungel, a senior civil servant who came into exile in May.

Some refugees in the Jhapa camps who say they have worked closely with the King, firmly believe that he is being hoodwinked by subordinates, while others are just as convinced that it is King Jigme, and he alone, that is the master mind behind the depopulation programme.

Even though the King has been touring the southern regions extensively since 1990 (23 times, reports Kuensel) those who were present at the time in Samchi, Chirang and Sarbhang say he was kept remote from the public. Despite the large crowds gathered at stage-managed events, only handpicked representatives were allowed to speak to him. The majority preferred to remain silent because of threats of dire consequences by the Dzongdas and Dungpas. These much-publicised trips south have public relations value internationally because they show King Jigme’s much-vaunted accessibility, but they do not seem to have provided him with insights on what is really going on.

On 14 July 1992, King Jigme once again travelled down to Geylegphug when he learnt that there was a mass exodus of Lhotshampas from Sarbhang. He reminded a gathering of peasants of all that his government had done for southern Bhutan and asked them not to leave their homeland in the hour of need. A few men and women came to the mic and said now that they had received His Majesty’s assurance, yes, they would now stay. But it did not work. The day after the King returned to his palace, the Nepali-speakers of Sarbhang, including those that had promised to stay, were shown the door by the local administrators.

Perhaps the King means well, but he does seem to have succumbed to coterie which desires cultural purity and unhindered economic access to the southern lands. For all his reported good intentions, King Jigme seems incapable of discerning his goal amidst a web of intrigue and vested interests that has been spun around him, especially since his marriage. Five of the most powerful members of the administration are related to the “new royal family”, as opposed to the Wangchuk family. They include Home Minister Dago Tshering, Foreign Minister Dawa Tshering, Social Services Minister Tashi Tobgyel, and Bhutan Army chief Gongloen Lam Dorji. Further, the Joint Secretary in the Planning Commission is Their Majesties the Queens’ elder brother; the final authority in deciding Bhutanese citizenship is the youngest brother.

Says Dhakal, “These young inter-related turks posted in key ministries are the backbone of the higher Bhutanese oligarchy and the architects of the southern political problem.” Says another refugee bureaucrat, “The cause for the southern problems is within the King’s immediate family, the programmes are made outside.”

Meanwhile, as the “new royal family” has centralised power, the King’s three sisters and his paternal uncle Namgyal Wangchuk, all of whom once had charge of key ministries, have been sidelined.

Says a former Drukpa official (like all Drukpas interviewed for this article, he wished to remain anonymous), “His Majesty does want to know the real suffering of the Nepalis, but the officials will never allow him to meet them. These people will never tell the King what he does not want to hear. The top brass in the army and the various lynpos (ministers) are colluding to such an extent that even the king is powerless.”

Western acclaim

A Western ambassador who is concurrently accredited to Thimphu and New Delhi, said in a recent interview: “Bhutan is a beautiful and well-preserved country, and the present Government is manned by very dedicated people. There is probably no other like it in the Third World. In Thimphu, they know exactly what they are talking about. The Bhutanese authorities take the initiative, they provide information when asked, and are very persuasive.”

This awe for the acumen of Thimphu administrators is matched by an appreciation of their lifestyle. The same ambassador: “Everything in Thimphu is on such a modest scale. When you are invited by a minister to his house, it is a family affair. Their hospitality is warm but so frugal. The government guest house in Bumthang is so simple: where else can you have a log fire like you can in Bumthang? The point the Bhutanese make is straightforward: we cannot afford to be swallowed by the Nepalis. They are still at a stage when they feel that the Nepali population is not at a suitable level. As soon as they feel that they have administrative control over the south, things will get better.”

When learned sahibs keep reminding you of your uniqueness, sooner or later you will begin to believe it. A change in self-perception leads to change in world view. Friends and associates become adversaries, if they have the ability to wrest your exoticism away and leave you where you were, a little-known and unimportant pocket hidden between the folds of the eastern Himalaya.

After the takeover of Tibet and the Dalai Lama’s exile, Bhutan came to the notice of Western travel writers as the kingdom where Tibetan (Mahayana) Buddhism remained sequestered. Nepal was only half-Buddhist and, anyway, was soon to sacrifice itself on the altar of mass tourism. In contrast, Bhutan’s picture postcard image has remained constant – green fields and forests leading up to monasteries that cling to clouded cliffs. High-cost, low-volume tourism has helped Bhutan’s exoticism to linger.

This incredible little country is ruled by a monarch who is modern, speaks chaste English, and yet is fervently in favour of maintaining cultural traditions. His country-in-the-clouds is doing “everything right” as it tackles development, Westernisation and international diplomacy. He is clever enough to “learn from the mistakes of Nepal”. He is out to save Bhutanese culture, forests and way of life. It is difficult not to support such a man and his programmes.

International acclaim has helped fuel Drukpa rejection of the Lhotshampas for their potential to ruin this idyll. The Druk Yul political chieftains took to heart the image that travel writers helped create in their coffee-table books. They decided to recreate the country in the image held by the West – culturally pure and ecologically pristine.

The glossy publications, and the Bhutan Government’s own tourist brochures, tell the world that ‘Bhutan’ equals ‘Drukpa’. One such popular picture book, Guy van Strydonck’s A Kingdom of the Eastern Himalayas: Bhutan (Editions Olizane, Geneva 1984), with 169 pages, has a single sentence on the Lhotshampas; they are “farmers who arrived in the country at the end of the 19th century and are now fully integrated Bhutanese citizens”. The rest of the book is on the Ngalung lifestyle and institutions, their Dzongs (forts), the western valleys, close-ups of monks and dashos, and whirling dancers. There is not one picture of a Lhotshampa, even in background.

The Drukpa image of Bhutan derives from the core regions of Paro, Thimphu, Punakha and Tongsa, whose “religio-cultural and political practices were accepted as the national ones”, according to A C Sinha.

There is every reason to appreciate the western Bhutan’s heritage and lifestyle; yet the overwhelming emphasis on the Ngalung ignores the population groups that are equally significant if not as interesting to outsiders. These include, cumulatively, the Sarchops; the Brokpa ‘aborigines’ of the high valleys; the multi-ethnic Nepali-speakers of the lower hills; as well as small concentrations of Totas, Santhals, Doyas and Rajbanshis.

The game plan

Even though Bhutan is a relatively easy country to govern, the Thimphu government is also among the more efficient in the developing world. The bureaucratic elite is almost entirely educated in the public schools of India and has a common work ethic, which also meshes with that of the King. Solidarity among the rulers, and the ‘manageability’ of their small, under-populated, resource-rich country, have enabled them to fine-tune development policy.

Perhaps the major accomplishment of the King’s administration (there has been no Prime Minister since Jigme Palden Dorji was assassinated) has been its ability to keep India placated even as Bhutan explores the boundaries of what the 1949 treaty of friendship allows. Today, Bhutan even has the leeway to negotiate independently with China on demarcation of its disputed northwestern boundary. While Nepal still dithers in indecision over selling hydropower to India, Thimphu is already earning from the Chukha Hydel Project. Since 1962, Bhutan has made a success of its postage stamps, which are renowned the world over for their “thematic value and technical excellence”. The Government even has the gumption to run (through agents) lotteries in India, which are said to turn in profits in the crores.

King Jigme’s administration is sharp, disciplined and responsive, with a reputation of “getting things done”. It is this administrative acumen that has been brought to bear against the Lhotshampas. The result has been devastating in its efficiency.

Somewhere along the way, a plan evolved. Its goal was to defuse the Lhotshampas’ demographic threat, and intricate details were worked out. A census would be taken again under more discriminatory criteria; Drig Lam Namzha would be strongly enforced; all political opponents would be termed ngolops and terrorists; schools, hospitals and services in the south would be closed; requirement of No Objection Certificates would be slapped on the southerners; all land found to be ‘illegal’ would be confiscated and northerners invited in.

This is what a confidential report of a Western bilateral development agency had to say about the period July 1991 to January 1992: “At this stage many ethnic Nepalese do not feel welcome any longer in this country. In the last year, they have been treated as second rate, in principle suspect, citizens. Their participation in public life has been made extremely difficult. There were no schools, no health facilities… sale of produce was difficult, trade licences were withdrawn and employment opportunities were initialised. If one then adds the fear of physical violence, it is no wonder that many families see no future in this country and decide to leave.”

A well-thought-out strategy of depopulation and ‘cultural cleansing’ is underway, and since February 1992 has been at its most aggressive. The picture emerges that the government’s hope is to empty the country of a large number of its legitimate Nepali-speaking citizens until their proportion is brought down to a ‘manageable’ level. Ratan Gazmere, who is now in Jhapa, says he learnt from reliable intelligence sources that the plan is to bring down the Nepali-speaking population down to between 15 and 20 per cent of the country’s reduced population. Foreign Minister Tshering told a visiting ambassador a few months ago that it was absolutely vital to “balance the demographic equation”.

The plan is being sold internationally with astute diplomacy that exploits all possibilities: Nepal’s fear of India, India’s fear of a pan-Nepali resurgence, the West´s soft spot for oriental Bhutan and a reluctance to bait India, the weakness of journalists when confronted with a kingdom in the clouds, and so on. Bhutan must rid itself of as many Lhotshampas as possible before negative international pressure builds up.

To give the benefit of the doubt to the Thimphu strategists, it might all have started innocently enough, with a simple idea that Bhutanese must be Bhutanese; One nation, One people. But, as the various parts of the plans were implemented successfully, the enthusiasm grew and stricter implementation followed. Before long, Bhutanisation had a momentum all its own, and the strategists seem to have gained confidence in their ability – as long as the world remained silent – of ‘reclaiming’ their country for themselves while the Lhotshampas were bundled off to Nepal, “where they belonged anyway”.

The 1985 Citizenship Act, the 1988 re-census, the Drig Lam Namzha code, the language policy, became the tools that began to be applied. The proof is in the silent, overgrown orchards of Samchi where today only rhesus monkeys roam; the youths hanging around listlessly at crossroads in the townships of Jalpaiguri District in West Bengal; or the broken spirits of torture and rape victims in the refugee camps of Jhapa.

Thimphu claims that the Nepali-speakers in the camps are actually illegal migrants – labourers from work gangs brought in to build the Bhutanese roads who stayed back, or those brought in privately to man the orange groves and cardamom plantations. The argument might be called ingenuous, were it not for the fact that the international community, and even the local politicians in the refugees’ own host community of Jhapa, are believing it.

Bhutan has always been strict about importing labour. In the past, the Dorji administrators of southern Bhutan kept close tabs on population movements, because revenue had to collected. In building roads and development projects (including Indian labourers to build Chukha), the Government ensures that there is efficient repatriation. In 1986, Nepali road labourers who had managed to remain behind were all rounded up – 15,000 individuals – and trucked out of the country. The refugee leaders say that Lhotshampas supported the action against illegal migrants.

What needles the Drukpa authorities as much as the presence of illegal migrants are the marital links that Nepali-speakers insist on making with non-Bhutanese nationals. Because Nepalis of all castes and ethnicities have a limited marriage market to choose from within Bhutan, many bring brides from outside. To counter this deviation, during the golden years of cultural harmony in the 1970s, cash incentives were introduced to encourage inter-Bhutanese (primarily Nepali-Drukpa) marriages. But the process of assimilation was obviously too slow for the impatient men who had taken over the country’s running.

The best non-Bhutanese spokesman for Thimphu’s present policies is Sunanda K. Datta-Ray, till recently editor of the Culcutta Statesman, who writes: “The kingdom has been increasingly worried not about its own subjects of Nepalese origin, but about constant flow of illegal immigrants from Nepal, Assam, Meghalaya and parts of West Bengal. Hence the 1958 cut-of date which is so bitterly resented… Indeed, the present agitation began only when a census was carried out in 1988 to weed out clandestine migrants.”

Code and census

In support of the drive towards One nation, One people, a royal decree was issued in 1988 demanding strict nationwide observance of Drig Lam Namzha, a code of social etiquette specific to the Ngalungs.

In one stroke, many years of building towards a united Bhutanese population was destroyed. Had it been voluntary, the package sweetened with economic incentives, it is likely that Lhotshampas would have gradually accepted at least the outward trappings of dress, etiquette and perhaps even language. But, as the King and senior officials have conceded, local officials ‘misinterpreted’ the decree and vehemently implemented their version. An investigation team was dispatched to bring extra-zealous officials to book, and half-hearted punishment was meted out to a few, but the code remains in force.

As Drig Lam Namzha was implemented, tailors hiked the price of ghos and kiras – traditional Drukpa male and female garments supposedly made from locally woven Bhutanese cloth, but actually mass-produced by factories in Ludhiana, Punjab. The heavy material is inappropriate for the south’s summer heat, but was made mandatory for the home, the field, office and school. While requirements are said to have been relaxed, the dress code continues to provide ample opportunity for harassment by the police. Penalty for a going without a gho is a week’s labour or Nu 150, of which the apprehending officer is allowed to pocket half.

In Thimphu, offices come to a standstill in the late afternoons as everyone goes to learn Drig Lam Namzha, which involves tuition in Dzonkha, and training on how to wear the Kamni scarf and how to bow with it, how to sit, how to address others, what hairstyles to keep, and so on. As the code was introduced, the teaching of Nepali in southern schools was dropped in February 1989.

While Drig Lam Namzha affected the Lhotshampa’s cultural identity, the census made refugees out of citizens.

A deliberate and well-organised policy of intimidation was set in motion to “encourage” the Lhotshampas to leave. Walk into any refugee camp and scores of refugees carrying Bhutanese citizenship identity cards will recall intimidation that ranged from being victimised by hooligans let loose on communities to the psychological distress of proving citizenship before dour officials.

A 1958 National Law, which was the first effort to define who was a “Bhutanese”, provided for citizenship by birth, registration of land holdings and naturalisation (five years’ stay). A census and land survey were carried out in 1972, which served as the basis for issuing nationality certificates.

In 1980, another census was conducted and citizenship identity cards distributed, and with it “the government completed the huge task of identifying Bhutanese citizens and distributing identity cards,” says Shiva Kumar Pradhan of the Bhutan People’s Party (BPP). “But with the 1985 Citizenship Act applied new criteria of citizenship, and made them retrospective, declaring all previous government action of granting citizenship as null and void.”

The attempts to implement the 1985 Citizenship Act through a census was not begun immediately, probably because the Gorkha National Liberation Front in adjacent Darjeeling District had just begun its agitation. Thimphu did not want any GNLF-inspired violence ruining its careful plans. The census was begun again in 1988, just after Subhas Ghising achieved his Hill District Council.

Amidst strident opposition from the south, the Tshongdo in November 1988 expressed satisfaction with the 1985 Act. In order to assist implementation, the authorities classified Bhutanese into seven categories, F-l to F-7. Only those who had land tax receipts for the year 1958 were given F-1 status and regarded as bonafide citizens. Other categories were denied the status, including ‘re-immigrants’ who had worked and lived outside Bhutan, children of non-Bhutanese spouses, and so on.

F-l was therefore the category to hold, but the retroactive application of citizenship back to 1958 papers was an atavistic requirement without precedent. No other proof of citizenship is accepted, including what had earlier been acceptable: the sathram (land registration) number, house registration number, payment of taxes, and the goongdawoola labour contribution.

Under the census-cum-identification exercise, Lhotshampas who had been trained abroad by the Thimphu government, who had worked for decades in the army or police, who have been Bhutanese teachers for all their working lives, who had ‘non-national fathers’, all were made illegal immigrants at the stroke of a pen. Citizenship cards issued in 1985 with the seal and signature of King Jigme were valueless.

Until January 1992, a No Objection Certificate (NOC) was required for all Nepali-speaking individuals who sought employment, admission in schools, trade licences, or even permission to leave the country on official work. Any whiff of an involvement in “anti-national” activities, even by distant relatives, meant that an NOC was unavailable. The NOC requirement has now been lifted, but the point is moot as F-l status-holders are also being evicted. If there is a ngolop in the family, the whole family has to leave, if not the neighbours and the whole community. The definition of ngolop varies, and can be applied loosely to all Nepalis-speakers that have left the country. To some Drukpa, all Southerners have become ngolops.

The confidential bilateral agency report quoted above says, “Individuals are held responsible for the deeds of family members. Furthermore, there are no clear guidelines for the term ‘family members’, and many have been forced to apply for emigration by signing the voluntary leaving certificates. Many of these families would be early settlers (1890-1930) who fall well within the 1958 census criterion.”

Recent arrivals in Jhapa say eviction is across the board and need no longer depend on the 1985 Act criteria. Villages are being emptied regardless of whether the inhabitants have citizenship papers, 1958 land-tax documents, or records of service in the bureaucracy, army or constabulary. Lately, even those who helped dungpas and dzongdas as informers (“Chamches”) to identify so-called illegals, or served extra-zealously as soldiers or prison guards, are arriving as refugees. A number of refugees have identified Lhotshampa policemen who they say had tortured them in Bhutan. “If you would turn against your own kind, what would you do to us?” the Drukpa administrators reportedly tell the chamcheswhen dismissing them.

Thakur Prasad Luitel, of Danabari Block in Geylegphug, 52-years-old and born in Bhutan of a father who moved from Sikkim, says the 1988 census gave him F-I status. He spent 9 months and 12 days in Phuntsholing and Thimphu jails, during which time he says he suffered extreme mental and physical torture. Meanwhile, his teenage daughter died at home for lack of specialised care. “When they released me, I thought my punishment was over, but then the Geylegphug Dungpa called us and said we must all get out.” Luitel says the Lhotshampa prison guard who tortured him in prison has been sighted in one of the refugee camps.

The departure is carefully choreographed. Villagers of Samchi describe the dungpa and other officials sitting before voluminous records. A Lhotshampa is led in to try to prove his 1958 status, and there are any number of ways in which he can be ‘found out’ – for example, of having hidden a marriage with a non-Bhutanese, or having been silent about a working stint in India and so on.

When families are declared ‘illegal’, they are forced to sign a ‘Voluntary Leaving Certificate’ which states that they are leaving of their own free will accepting the compensation that is provided. Each family is then asked to have a black and white group photograph taken and to bring in eight copies for the files before they depart. Refugees also speak of tape-recordings or video-recordings in which officials exact verbal confirmation that the departure is voluntary.

‘Travel expenses’ are paid out of the ‘compensation’ for the properties Lhotshampas leave behind. In Samchi, the ‘compensation’ was initially set at Nu 40,000 per acre of paddy field, but this figure was continuously scaled downwards until families got no more than Nu 4,000 per acre. In Chirang, some villagers who had been put behind bars had Nu 2,000 per month of prison stay deducted from the ‘compensation’ they received. A few families managed to steal away without accepting compensation or signing the government’s forms, while others collected as much documentary evidence of their house and lands as they could to prove at some later date that the property was theirs’.

Dal Bahadur Rai is an Indian national who works as a guard in a tea-estate in Jalpaiguri District, just astride the open border. His Bhutanese neighbours are the villagers of Ahaley and Chargharey, in Ghumauney Block, Samchi District. Rai says: “In Ghumauney Block, there were 684 households. Today, there are only four. They are of the Mandal (headman) whose name is Homagain, Dataram Rijal, Bhakley Giri and Chandru Magar. When the rate for paddy fields was 32,000 rupees per acre, the Dahals of Ahaley sold 10 acres and made good profit. But then the rate came down and now the government gives only 3,000. Rather than take the money and give up their land forever, people like Parsuram Kafle and Sete Sanyasi sneaked away before the Dungpa could force them.”

Across from Rai’s property in Jalpaiguri, the fields are empty and the villages silent. The next step is said to be the announced programme of resettlement of northern Drukpas in the vacated lands of the south. According to the Secretary of Bhutan’s Department of Survey and Land Records, more than 47,000 acres of illegal land have been freed in Samchi alone, and the Tshongdu for its part has resolved that “illegal land holdings in the southern districts should be allotted first to security force personnel and the Militia Volunteers”. The Chief Operations Officer of the Royal Bhutan Army has expressed “deep appreciation for the proposal”.

“The government’s idea of a permanent solution for Bhutan’s problem seems to be that of a more mixed population in the southern districts,” says the bilateral development agency report quoted above. It adds that currently preparations are underway for the first such resettlement in Samdrup Jonkhar District.

***

~ Kanak Mani Dixit is founding editor of Himal Southasian.

~ This article was first published in our July-August 1992 print issue. Also read Part I and Part III of the reportage.

The dragon bites its tail – Part III

17 OCTOBER 2018

FROM THE ARCHIVES: Part III of our longform reportage from 1992 on Bhutan’s Lhotshampa question.

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru meets King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck during his 1958 visit to Bhutan.

Photo: Public.Resource.Org / Flickr

(This article was first published in our July-August 1992 print issue. Also read Part I and Part II of the reportage.)

Thimphu high society

Drukpa society is made up of a small educated super-elite of perhaps no more than one thousand (mostly male, even though the traditional society is matriarchal) and a large peasantry. The former are all in bureaucracy or in business, with their interests intimately tied with those of the state. There is no peer support for non-conformists who might question the basis for policies of state, such as the hardline crackdown against the Lhotshampas.

According to Rose, there is a “virtual non-existence of competing elite groups” in Thimphu, which means that there are no dissident members from among the traditional elite nor the modernised bureaucracy. To the extent that Bhutan has “no non-official educated elites of any size or significance”, therefore, Thimphu is an intellectual backwater. There is no one to challenge programmes designed and implemented by the administrators of the country or the conservative monastic order. The Lhotshampa civil servants who have dared to ask questions are all in exile or prison. Those that remain are increasingly marginalised, but remain silent.

Om Bahadur Pradhan, Minister for Trade and Industry and highest-ranking Lhotshampa, is son of Nyaulibabu, one-time commissioner of Samdrup Jonkhar. He has served as Permanent Representative to the United Nations in New York. Pradhan is a student of Drukpa Kagyu philosophy, speaks fluent Dzongkha and is married to a Sarchop. Some refugees who know him well consider him “more Drukpa than the Drukpa.” A former colleague of Pradhan is angry that he does not use his access to the King: “Why does he not speak? He knows his father settled Nepalis in eastern Bhutan upon the express request of the Bhutanese government.”

Says Bhakti Prasad Sharma, an activist who was recently released, “Om Pradhan is in a fix. He is disillusioned, but he is neither here nor there.” However, Pradhan did recently arrange for a group of Nepalis to approach the King with a petition detailing discriminatory treatment, and at the autumn 1991 session of the National Assembly, he did remind members that “not all Lhostshampas were ngolops”.

The reticence of the Bhutanese civil servant is not a new phenomenon. It has been evident for decades among Bhutanese diplomats at the United Nations and at international conferences, and more recently at SAARC parleys and at ICMOD in Kathmandu. Today, this unwillingness to speak up has become a great asset as inconvenient questions are never answered.

The bureaucrat´s extreme caution on political matters is also born of economic self-interest. The First Class Gazetted Officer and ranks above have perks that best all South Asian counterparts – including the facility to buy a new vehicle every five years, easy access to Royal Bhutan Insurance Corporation´s beneficence of low-interest loans, and duty-free liquor privileges. Much of the real estate in Bhutanese towns are bureaucrat-owned. Pradhan is said to have four mansions besides the one he lives in, and Dawa Tshering is the second biggest real-estate tycoon in Thimphu.

Tshering, who has the distinction of being the world´s longest serving foreign minister, has emerged as the spokesman of the Government´s policies, even though it is said he was not part of the original coterie that planned the exercise. The Lynpo apparently got wedded to it after his daughter married into the new royal family. Lynpo Tshering is the son of a Kalimpong Chinese and was brought up in a Nepali household there. He has a Bachelor of Laws degree and was a hostel superintendent in Kalimpong before he landed it big in Bhutan under the tutelage of late Prime Minister Dorji.

There might be little ´intellectual culture´ in Thimphu, but there is plenty of high society to reap the largesse of the foreign donors and tourism, and economic policies that are increasingly tailored to suit the needs of a few. The jet-setting Drukpas are within striking distance of an exclusive Western standard of living. Druk Air´s BAe 146 jet allows them instant access to New Delhi and Bangkok. The Bhutanese highways, built and maintained courtesy the Indian Border Roads Organisation (known locally as ‘Dantak’), carry Toyota Land Cruisers and air-conditioned sedans with ease. Plebeians and Indian traders drive Maruti Gypsies.

High society is almost totally Westernised. The dasho who gives a speech on cultural purity will enter the toilet cubicle of the Druk Air jet out of Paro Airport as soon as the seatbelt sign is off – to struggle out of his gho and emerge transformed in jacket and tie. At the border town of Phuntsholing, next to the bus stop, men and women change from traditional to Western attire, or vice versa, jettisoning their Drukpa identity with apparent ease. In Thimphu, under cover of the night, the children of the elites drive to celebrate the National Day with all-night jam sessions, in jeans and skirts.

It is a lifestyle in a dreamland which, goaded by Western and Indian plaudits, is increasingly divorced from Southasia. Thimphu´s ruling class rarely visit the south, except to reach the Indian border. There is little empathy in Thimphu circles for the Lhotshampa peasantry which populates the south, and whose best and brightest actually work amongst them. As a Kuensel reporter admitted, it was only the killing of a Ngalung Dungpa at Geylegphug in mid-May that “brings to the Bhutanese people the real gravity of the disturbed situation in the kingdom”, whereas before “reports of terrorism in remote villages were vague in their anonymity and distance”.

In Thimphu, self-righteous indignation tends to greet Lhotshampa demands for equal treatment. “Especially in the period from October to December 1991 (around the very conservative National Assembly), mutual distrust (between the Northern and Southern Bhutanese) was at a peak, with Drukpas very tense and defensive,” says one development agency report to headquarters.

A Drukpa official passing through Kathmandu in May (who also did not want to be identified) clearly encapsulated the view from Thimphu when he said: “You must not believe this talk of Thimphu´s closed culture. Actually, the people in Thimphu are by nature open. The young intellectual group is sharp and will act. There is no racism as such, but a feeling that this thing should be allowed to take its course. A minister like Dago Tshering might seem to be hardline to outsiders, but he is articulating the threatened feelings of the Drukpa elites and commoners alike. Democracy will probably come when the society is ready for it. Meanwhile, let us not bullshit the farmer. The main thing is to educate the population, which is why there is so much emphasis on education in the national budget. The southern problem has emerged not as an initiative of the Government but as a response to the anti-King activities. Those that call themselves refugees are not leaving because of brutality. Their departure was voluntary.”

Ngalungs such as the official quoted above, when asked about their society, will emphasise its egalitarian aspects, the absence of caste, and the links each family has with the home village. But it does appear that the class structure is becoming rigid to exclude not only the Lhotshampa, but also a majority of the high mountain peasantry which remains remote from Thimphu’s bustle. Inter-marriages and enmeshing of interests among the elite families – the Wangchuks, the Dorjis, or the newly ascendant family of the Queens – results in a see no evil, hear no evil mentality.

Opposition in absentia

So, who are the ngolops? Going by Government pronouncements, the most dangerous one would be Tek Nath Rizal, who was the first Lhotshampa leader to be harassed into exile. Abducted and brought back to Thimphu, he is today the senior most ngolop in prison.

Rizal was a civil servant who had impressed the King with his straight talk and dedication and had risen to become member of the Royal Advisory Council. In April 1988, when alarming reports arrived from Chirang of discriminatory implementation of the census, Rizal and another Councillor from the south took the help of Thimphu’s Lhotshampa civil servants in drafting a petition and submitted it to King Jigme.

“The people of southern Bhutan most humbly beg Your Majesty for protection and relief,” the petition stated, asking that he disallow the retrospective effect of the 1985 Citizenship Act. The petition recalled that the review of the 1977 Citizenship Act had been done at the initiative of the southern Bhutanese, who fully shared the concern about possible settlement of illegal immigrants, “… to view the people with suspicion and to blame them for allegedly colluding with the immigrants to secret them into the country is unfair and unjust.”

Rizal’s action was considered treasonous, and he was imprisoned for three days and his Councillorship terminated. In the face of increasing harassment, he left the country at the end of 1989 with two associates and ended up in Birtamod, a junction town in Jhapa District of Nepal. There they set up the People’s Forum for Human Rights (PFHR) “to fight for political equality in Bhutan and to inform the world about the happenings within”.

With the assistance of Ratan Gazmere, then a lecturer at the National Institute of Education in Samchi, a booklet Bhutan: We Want Justice was produced by the exiles. Rizal and his two companions were abducted from Birtamod by Nepali police and taken to Kathmandu. Waiting on the tarmac was the Druk Air jet with V. Namgyal, King Jigme’s aide de camp and chief of the Royal Bodyguards. They were handcuffed and taken to Thimphu.

Soon after the abduction, thinking perhaps the leaderless Lhotshampas would not react, the government legislated the wearing of the gho and the kira “for all Bhutanese at all times”.

The first refugees began to leave Bhutan. They were housed with the help of West Bengal´s ruling party CPI(M) at Garganda, a tea estate community in Jalpaiguri, where large sheds of a tea companies were made available. The PFHR and the Students Union of Bhutan combined forces in early 1990 to establish the Bhutan People´s Party in Garganda.

Later, the refugee camps in India were dismantled and refugees who did not have relatives and friends all moved west into Nepal, where they began to populate the banks of the Mai Khola in Jhapa. The BPP, meanwhile, established an office in Kathmandu and began a media campaign. But the Kathmandu media’s reach was short, and the BPP ended up preaching to the converted.

As the Bhutanese programme of depopulation progressed, not only the southern peasantry but also the high-level Lhotshampa civil servants in Thimphu started feeling the heat. Ten civil servants fled in April 1991, and others followed. The arrival of these senior bureaucrats, some of whom had helped draft Rizal’s original petition to the King, provided a degree of political articulation not previously present Unexpectedly, however, their presence sparked infighting and rivalry among the refugee front ranks.

The politico-bureaucrats who entered the scene first tried to carve a niche for themselves within the BPP, but they claim to have found a party that was ill-organised, lacking realistic programmes and a constitution or ideology. Above all, they criticise BPP leaders of harbouring idealistic visions of a ‘free Bhutan’ without searching for realistic ways to push forward the agenda of return.

Unable to make headway with the BPP, some civil servants joined the Human Rights Organisation of Bhutan (HUROB) which, as PFHR´s successor, was involved in managing the refugee camps. Others decided to form the Bhutan National Democratic Party, as a ‘democratic alternative’ to the BPP. The new party was launched in the fall of 1991 in New Delhi, signifying a shift in lobbying focus.

Rightly or wrongly, the BPP is identified with the left, while the BNDP sells itself as the moderate party to which the Thimphu Government will have to turn to for negotiations when the time comes. King Jigme did tell Reuters that the southern problem could be solved through “honest, sincere and genuine dialogue”, but that “dialogue had been difficult with the BPP… because they had no clear leader”.

For their part, the BPP stalwarts regard the BNDP as a party of well-to-do interlopers out to wrest away a movement that they have nurtured from the start. One European journalist who has her sympathies with the BPP says the BNDP people is made up of ‘armchair activists’ who “tried to get the movement under their control, confused everyone, tried to divide the movement, but did not succeed”.

Pratap Subba, who presently works for HUROB as an organiser at Pathari camp, says he left the BPP because of differences in ideology and strategy. “The public should be the last weapon to use; instead, they gave the call for mass rallies against the government with no back-up support. There was no media coverage, and a lot of false talk to mislead the people.” The BPP, says Subba, “spends more energy fighting the other refugee organisations – SUB, HUROB and BNDP – than for the cause of return.”

S K Pradhan, General Secretary of BPP, accuses the BNDP of dealing a fatal blow to opposition unity and sowing “absolute confusion” among the refugees. “They want security and a comfortable stay in Kathmandu, whereas our people are on the ground, organising in the Duars, the Hill Council areas, and even within Bhutan.” Pradhan says the BPP plans to restart agitations “within 1992” but will not divulge details as to what form they will take.

Try as they might to give a non-ethnic colour to their politics, the parties in exile have failed to enlist a single prominent dissident, either Ngalung or Sarchop, in their struggle. BPP´s Pradhan claims some Drukpa membership, but they are not visible. The BNDP stated at its founding that it expected “to dilute the allegation of ethnic-led struggle”, but the few Sarchops in exile have not yet come on board.

BNDP´s General Secretary Dhakal remains hopeful that the distinct political choices presented by two parties will allow “liberal thinkers from the Sharchops and Ngalungs to take a political stand on the crisis in Bhutan.”

What Bhutanese politics in exile lacks, clearly, is a figure to rally behind. “Because we lack a leader, there is a dilemma in the camps,” concedes Subba. Such a figure exists in Tek Nath Rizal, which is probably why Thimphu does not release him even when his cellmates have been let go earlier this year. After a long stay at the army-controlled Rabun a prison in central Bhutan, he has recently been moved to the Central Police Prison in Thimphu.

Does Rizal have what it takes to lead the refugees back to Bhutan? A refugee teacher who knew Rizal since childhood says, “He has charisma and obvious honesty. He has the ability to bring unity among the refugees. But I do not think he had the theoretical grasp to put forward the design of the new Bhutan after we go back.”

So, the BNDP and BPP are not on talking terms, either in Kathmandu drawing rooms or in the Jhapa camps. Regardless of their different approaches, however, neither party has yet succeeded in breaking the impregnable diplomatic and media barricade that Thimphu´s master diplomats have erected around themselves.

“So far, exile politics has reflected our upbringing in Bhutan. In the beginning, we had no political culture, knew nothing about forming a party, or about ideology. So, we have been learning,” says Dr Bhampa Rai of HUROB. He is concerned that sooner or later the refugees will become pawns in party politics of Nepal. “Nepali politicians must look at us refugees – not as Leftists or Democrats, but as Bhutanese. When we go back, then of course we will divide along where our ideologies lie.”

Ratan Gazmere is despondent about the state of exile politics. “The PFHR we started was to have been a non-partisan organisation fighting for human rights. Coming out, we find that refugee politics is steeped in power struggle. Those of us who have just come out see it as our prime responsibility to bring people together, to have unity, and to internationalise the issue.”

Bhakti Prasad Sharma, who was released in December along with Gazmere, says, “The movement is in shambles. There is no united front because an element of ego has crept in.” The five erstwhile prisoners, he says, were “very concerned and are talking to each other. The coming months are critical, and the priority should be to return with dignity. We can fight for reforms in Bhutan, but only after we go back. Human rights and democracy cannot go together, one has to precede the others.”

Bringing up the question of human rights and democracy, Sharma has put his finger on one of the principle issues up for discussion. The political crisis in southern Bhutan, coming as it did soon after Nepal’s successful “peoples’ movement for human rights and democracy” of April 1990, suddenly thrust political novices forward as refugee leaders. These leaders picked up the terminology presented to them by the Kathmandu tabloids. The Bhutanese problem, too, became, simplistically, a movement for human rights and democracy. Whether this was realistic, was a different matter.

BNDP’s R B Basnet, one of the senior bureaucrats who came out in 1991, has no doubts, “Political reforms are necessary to guarantee human rights. It is not possible to have respect for human rights in the absence of democratic institutions.” This might be true, but the word ‘democracy’ is as anathema to Thimphu´s aristocracy as it was to the Ranas of Nepal in the 1940s. It is unlikely that the Druk Gyalpo would be as amenable to opposition demands for democracy as Nepal’s Sri Panch was in the Spring of 1990.

The pages of Kuensel amply demonstrate how remote the Thimphu rulers are from accepting the one person, one vote principle. In October last year, Foreign Minister Tshering asked the Tshongdu not to be confused with the anti-national’s campaigns against dress, language, custom and religion. They had “a much more deep-seated, long term objective”, which was “the introduction of multi-party democracy”.

Once democracy was introduced, warned Lynpo Tshering, the Lhotshampas would be in a position to form the government in Thimphu and take over the country. The combination of “ethnic demands” for constitutional monarchy, multi¬party system and proportional ethnic representation in the National Assembly and the Cabinet, he said, would be “a highly lethal one for the Bhutanese monarchy”.