Kunal Purohit 30 Dec, 2019 This Week in Asia

- With at least two major regional elections in 2020, all eyes are on how the BJP will arrest the fallout from the citizenship act and local poll defeats

- Analysts say the BJP will concentrate on centralising power and a hardened focus on Hindu nationalism

December was a difficult month for Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Amit Shah, his top lieutenant in the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The BJP is facing the biggest challenge of its five-and-a-half-year rule as it scrambles to defuse crises on multiple fronts. How Modi and Shah, the home minister, respond to these problems could determine whether the party maintains its comfortable political edge over rivals, observers say.The current problems – mass protests over a controversial citizenship law and back-to-back state election defeats – are seen in some quarters as an early sign that the public is pushing back against their aggressive advocacy of the Hindu nationalist agenda over broader national interests.

The two men are lifelong members of RSS, the hardline Hindu nationalist group that serves as the ideological fountainhead of the BJP.

Political researcher Neelanjan Sircar said the state election defeats also happened “due to the BJP’s desire to centralise power in Modi and Shah. It does not want strong regional leaders and units”.

At the moment, the biggest headache for the BJP going into 2020 is the mass protest action around the country over the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act, which was passed on December 12. The law paves the way for immigrants from non-Muslim minorities from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh to obtain Indian citizenship.SUBSCRIBE TO This Week in AsiaGet updates direct to your inboxBy registering, you agree to our T&C and Privacy Policy

Demonstrators, many of whom are students, say the legislation brings out into the open what they claim is the BJP’s plan to systematically drive out the country’s 200 million Muslims as it seeks to create a Hindu Rashtra, or a Hindu nation.

The belief is that the CAA, along with the government’s plan to initiate a National Register of Citizens, will create a scenario wherein Muslims who do not have documents to prove their citizenship will be declared illegal immigrants. Hindus and other minorities will not face such a predicament.

Modi and Shah have found themselves in an embarrassing bind over this issue because while Shah had explicitly outlined this plan in multiple speeches – saying it targeted “infiltrators” and not Muslims – Modi came out after the protest to directly contradict this position. The prime minister declared his government had no plans to implement the National Register of Citizens.

ELECTION SETBACKS

If this was not enough of a quandary, the BJP is also reeling from two setbacks in state elections.

Earlier in December, the BJP’s oldest ally, the regional party Shiv Sena – with which it has partnered for 25 years – cut ties with the Modi administration and formed a coalition government with the opposition Congress to govern the state of Maharashtra following state polls there.

On Christmas Eve, the BJP lost power in Jharkhand, a small but crucial state which holds 40 per cent of India’s mineral wealth. Despite ruling the state for five years, the BJP could only manage 25 seats in the 81-member assembly, while the Congress and its ally got 46 seats. This was its fifth major loss in regional polls in the last year.

With at least two major regional elections in 2020, in the capital New Delhi, and in the eastern state of Bihar, all eyes are on how Modi and Shah arrest the fallout from the citizenship act saga and the poll defeats.

Also weighing on their popularity is the slowing economy, which grew at its lowest rate since 2013 in the July-September quarter.

Sircar, an assistant professor at the Ashoka University in the state of Haryana, cautioned against using state poll results as a crystal ball into Modi and Shah’s longer term fate as the ruling party had been struggling to win state elections even before it cruised to a general election victory in May.

India’s Narendra Modi defends citizenship law, as protest deaths rise22 Dec 2019

The Congress, which held power for decades and which continues to be led by the country’s influential Nehru-Gandhi clan, swept regional polls in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan months before the general election.

But what the results do reveal is that local elections are no longer swayed by Modi’s popularity alone, said Sircar, whose research interests include studying election data.

After 2014, when Modi first came to power, his party won state elections in most major states and governed over 70 per cent of India’s land mass until March 2018. This has now come down to half, partly due to the BJP’s efforts to centralise power in the two leaders, said Sircar.

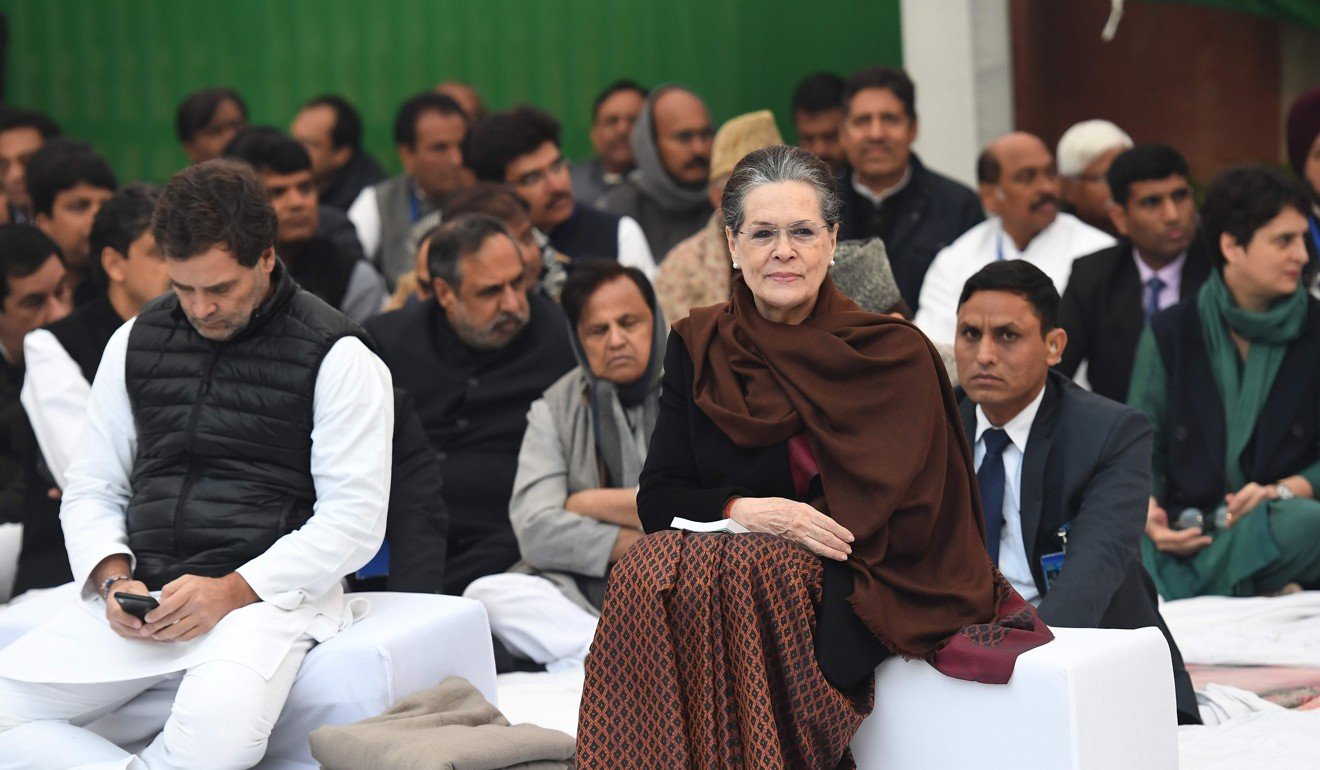

Meanwhile, continuing confusion in the opposition ranks is harming efforts to build an anti-BJP front. The Congress, for instance, still has a temporary party chief in Sonia Gandhi after her son and former party chief Rahul Gandhi quit, taking blame for its election defeat. The fragmentation of opposition unity is likely to rear its head during the upcoming Delhi elections, in which the Congress might not want to ally with the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) to defeat the BJP.

HONEYMOON PERIOD

Another crucial reason why the current situation might not affect the BJP’s long-term standing is timing. There is an important reason it introduced the legislation in the first six months of its five-year term.

“The BJP has been very effective in setting its own narratives and winning elections. Hence, while it does seem like the BJP is floundering, it is too early in its term for it be considered a threat to their popularity,” said Sudha Pai, a retired professor in political science from New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Criticise Modi? Big business wouldn’t dare, says Indian billionaire 1 Dec 2019

Pai points to the 2019 elections, when Modi managed to divert attention away from issues such as development, infrastructure, a slump in the economy and the highest unemployment rate in 45 years, to rake up nationalism against Pakistan and come back to power with an enhanced margin.

The BJP has probably learned this from experience. In 2016, India’s campuses were rocked with student protests against the government but this did not feature in the discourse during the general elections. The face of the protests, youth activist Kanhaiya Kumar, lost by over 400,000 votes to a controversial BJP leader, Giriraj Singh.

COURSE CORRECTION?Since Modi’s re-election in May, his government’s two major moves – the decision to revoke Jammu & Kashmir’s special status and bifurcate the state, and the citizenship law amendment – have seen a similar approach being employed. Both were passed in Parliament without much debate, despite acrimonious opposition.

Even in the face of the protests, Modi and Shah have remained defiantly supportive of the police action, which has so far resulted in 23 deaths. Most of these occurred in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, where the BJP’s controversial chief minister Yogi Adityanath hailed the police crackdown.

But both Pai and Sircar believe the protests and Jharkhand defeat will come as a rude shock to the BJP. “No matter what the final outcome is, there is a sense that the mood in the country is changing, that nationalism might not be enough to win elections any more and that the BJP is not invincible,” said Pai.

Such widespread protests have not occurred in the last few decades. “Somewhere, this is affecting Modi’s popularity, bit by bit,” Pai said.

Opinions are mixed on whether these issues will result in a course correction in the next four years of the BJP’s term.

Sircar does not see a shift by the BJP any time soon. “I don’t see the BJP’s model changing. Centralising power in their own hands is a very important project for both Modi and Shah. Taking decisions without consultation is also integral to it; to consult means to slow down the process,” said Sircar.

Pai, however, is slightly more optimistic, but also believes the next four years will see a hardened focus on Hindu nationalism. “It depends on what happens with the protests and how long they sustain. But I think the BJP will realise that nationalism and warmongering have diminishing returns. It will have to deliver.”