Image credit: Sunday Observer

N Sathiya Moorthy 5 Augusty 2018

News reports about Srimathi Chinthrangani Wijeweera, wife of JVP’s dreaded founder, Rohana Wijeweera, filing a habeas corpus petition in the Court of Appeal for the Sri Lankan State to produce her husband, comes up with possibilities. Coming as it does 500 days after the Tamils’ protest outside the Kandaswamy Kovil in Killinochchi, seeking justice for their dear ones missing since in the ‘LTTE wars’, the 62-year-old Chitrangani Wejeweera’s could well trigger a spate of similar petitions from parents and spouses, siblings and children of other ‘missing JVP cadres’ and ‘innocent Sinhalas’, men and women, young and old, seeking to know the whereabouts of dear and near ones, who had not been seen since the commencement of the ‘Second JVP insurgency’, 1987-89, or a full generation of 30 years back.

Sad but true, as 62-year-old Chinthrangani, residing in the Welisara Navy Camp, seems to contest claims that her husband was dead, whatever the reason and whatever the mode and method. As per media reports, her petition before the Court of Appeal submits that does not believe TV newscast that Rohana Wijeweera was dead. The argument seems to be that as she had seen him alive on television, but Rohana’s ‘corpus’, or body, was not shown likewise, dead or alive, for her to come to any conclusion. Nor had anyone provided any official document to her of any inquest, magisterial inquiry or any such legal process, to prove Rohana was no more, the petition states further.

Chithrangani now wants a court order, directing the Sri Lankan State to produce Rohana, to be dealt with, according to the law of the land. That is to say, if Rohana had committed any crime, he could still be brought to book, the petition seems to aver, but before that it wants him produced – dead or alive.

The mother of “six children who suffered immensely due to their father’s detention and disappearance”, Chithrangani claims to have been “kept in protected custody and thereafter semi-detention to date”. As if to explain the delay in her being able to move the courts, the petition reportedly claims that Chithrangani “has not had the freedom to seek legal action until recently and is even scared to come forward to file this case”.

Tortured, roasted

Naming Maj-Gen Janaka Perera, Captain Gamini Hettiarachchi, Lt Karunarathna, Col Lionel Balagalle, Maj-Gen Hamilton Wanasinghe, Maj-Gen Cecil Waidyaratne, former Defence Minister, Gen Ranajan Wijerathne, former Secretary of Defence, Gen Cyril Ranatunga and the Attorney-General as respondents, the petition claims that Janaka P, who was a Brigadier at the time, and two officers named immediately after him had arrested Rohana Wijeweera at St Mary’s Estate in Ulapane, and “has been illegally detained in the illegal custody”.

That was all in November 1989, going also by other reports and personal accounts from the period, when the ‘Second JVP insurgency’ was drawing to a close, so to say. At least later-day media reports, citing ‘eye-witness accounts’ from the period, have claimed that Rohana was tortured and shot, and he may have been thrown alive into a ‘gas plant’ and that he ‘groaned loudly’—the last of the ‘rites’ undertaken at Borella Cemetery, in the heart of the capital city of Colombo.

Chithrangani’s petition rather graphically describes the day (12 November 1989) and way her husband was arrested and taken away, while the so-called eye-witness accounts, including those carried by BBC. One such report by a local daily quoted Indrananda de Silva, who claimed to be an Army photographer at the time and also claimed to have been present at the place – as he told an interviewer as late, or as recently, as mid-November 2014, or full 25 years after Rohana went ‘missing’.

Kangaroo courts

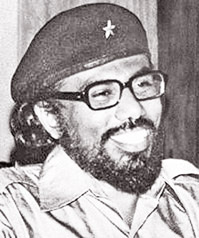

Born Patabendi Don Nandasiri Wijeweera on 14 July 1943, Rohana Wijeweera went by very many aliases such as Aththanayaka Mudiyanselage Shantha Nimalasiri Aththanayake. A ‘Stalinist icon’ who styled himself after Che Guevara, as most left-leaning youth across the world had done at the time and since, Rohana dropped out from medical course in Moscow’s Lumuumba University, to return home and launch the JVP, a very militant extension of the substantially strong traditional Left in the country. As much as the pity and empathy that Chintrangani’s petition now seeks to evoke, the JVP under Rohana was among the most brutal of international militant/terrorist organisations, with its ‘people’s court’, which were ‘kangaroo courts’, meaning and ending in torture of what the outfit unilaterally dubbed the ‘people’s enemy’ – as with the rest of them, then and since.

That was so until a decade later, before teenager Velupillai Prabhakaran took his first shot, at Jaffna Mayor, Alfred Duraiappah, up North, in 1975 – and founded the even more rugged LTTE, which was as much a terrorist as the Tamils had been terrorised by organs of the Sri Lankan State. Only four years earlier in 1971, the JVP had launched the ‘First Insurgency’, which the Government quelled with Indian military assistance at the right time.

The JVP was known to have “killed Buddhist monks, academics, trade union leaders and even a popular politician-film-star, Vijaya Kumaratunga, whose wife Chandrika-Bandaranayake later became President”. Ironically, the LTTE later assassinated President Ranasinghe Premadasa and his Defence Minister Ranjan Wijeratne, “who was present at Wijeweera’s death”, for reasons far removed from Rohana’s ‘disappearance’. Rather, Prabhakaran’s ‘Black Tigers’ suicide-squad killed them as ‘enemies of the Tamil people’, so to say.

Maj-Gen Janaka Perera, who joined the UNP at the time died in a bomb-blast in Anuradhapura during a poll-campaign in 2008. While the LTTE was the prime-suspect as used to be the case under the circumstances of the times, for a short period, the JVP’s name also got linked. As the JVP of the times had main-streamed itself so very completed, the rumours died as fast as they came up. There were also no reports of any underground arm of the ‘Rohana JVP’ existing, to avenge his ‘death/disappearance’.

Killed by the thousands

This is not the first time since Rohana’s exit from the scene that Chitrangani and her children are in the news. In 2003 or thereabouts, the court ordered their oldest daughter to an extended remand period after she began attacking her mother and siblings in the Navy quarters. Media reports at the time also claimed that the behaviour owed to ‘childhood trauma’.

Chithrangani was again in the news more recently, in 2015, when the JVP claimed that they were funding and financing Rohana’s family. A statement appeared in her name that no such help came their way.

The public exchanges followed the Navy’s declaration that Rohana’s family did not require their security anymore and they would have to fend for themselves – or words to that effect.

What however lends immediate relevance to Chithrangani’s court petition is the ongoing international pressure on the Government, on the strength of UNHRC Resolution 30/1 co-authored by Sri Lanka. The resolution calls for and/or promises the setting an ‘independent, international’ probe into ‘war crimes’ and other ‘accountability issues’ flowing from the conclusive ‘Eelam War IV’ between the armed forces and the LTTE (2006-09).

The incumbent Government has at best been wishy-washy in setting up a probe of whatever kind into ‘war-crimes’ charges from the LTTE era.

Still, it has haltingly set up an ‘Office of Missing Persons’ (OMP) for first producing a list of those Tamils, militants or civilians, who may have gone missing during the war time, never to return as yet. By implication, the reference is to ‘forced disappearances’ of the ‘Rohana kind’, when there may be witnesses testifying to the (unrecorded) ‘arrest’ of Tamils, who have not been accounted for, thus.

In context and contrast to the Tamils’ approach to moving the international community and the UNHRC through them, demanding ‘justice’ for their ‘missing men’, Chintrangani has now approached the Sri Lankan State system, through the nation’s higher judiciary, for ‘justice’ to her husband. What more, Rohana Wijeweera was not the only one to ‘disappear’ that way, and the kin of Rohana’s ‘comrades’ might now be encouraged to do so, though their numbers, if at all remain, to be seen.

It’s not without reason. With Emergency in full force and the armed forces at it, as much as they may have been two decades later against the LTTE, various assessments have put the number of the JVP cadres and innocent Sinhala civilians killed in the 1987-89 period anything between 60,000-100,000. This compares with the 40,000-180,000 Tamil victims of the armed forces, as claimed/reported since the conclusion of ‘Eelam War IV’ – as against the 7000-8000, as ‘accepted’ by the international community in the early weeks and months.

There was however a difference, if that is at all any. According to some reports, quoting ‘secret’ and at times unpublished studies from the ‘Second JVP insurgency’, most rivers across the Sinhala South were ‘running red’ with the blood of all those youth killed, rather brutally and at times unarmed. No records of the kind existed in those days of video photography and the like, as has been used to ‘substantiate’ the number of Tamils killed, yes – but that may mean nothing.

Reproductive generation

The irony of such claims, be it those of Sinhala youth in the late Eighties or the Tamil brethren two decades later, they were mostly in the re-productive age-group. It means that with their death, future generations of Sinhalas and Tamils may have been exterminated without notice, and maybe without adequate cause or justification. How sections of the international community would want to describe the armed forces’ killing of the ‘JVP generation’ if to some of them the later-day Tamil-killing was ‘genocide’ or whatever, remains to be seen, if and when flagged.

Chithrangani’s court case may be one possible occasion, though it may be too early to say.

There is a reason for all this – and even more. As may be recalled, in the months, not even years after the May 2009 conclusion of ‘Eelam War IV’, news reports talked about the recovery of human skeletons buried in a heap in what used to be ‘JVP land’, and said that they might have been armed forces’ victims from the 1987-89 JVP insurgency. Though sections of the media claimed immediately that they may have been ‘Tamil victims’ of the armed forces, later it was said to be those from the ‘JVP era’.

Then there was the case of Premkumar Gunaratanam, incidentally a Tamil leader of the JVP from Trincomalee, who had gone underground at the time, acquiring Australian citizenship, and returning home, post-LTTE war, only to be arrested by the police during the Rajapaksa era. He has since served a jail-term for travelling under an alias, and has become a Sri Lankan citizen all over again, launching the breakaway JVP’s ‘Frontline Socialist Party’ (FSP) but with little political impact.

Huge problem

As it happened, the UNP was in power at the time of the ‘Second JVP insurgency’ and ‘cadre-killing’ by the armed forces. This contrasts with the killing of ‘innocent Tamils’ by the armed forces under SLFP presidency of Mahinda Rajapaksa. In a way, it is a political tit-for-tat, but then a whole new generation of Sinhalese in the South may not relate as much to the distant past as the present-day Tamils still can and are identifying with whatever ‘happened’ only a decade ago.

This apart, both the Rajapaksa-centric SLPP-JO and the UNP of incumbent Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe may be cautious to put the nation’s armed forces on the defensive any more than UNHRC 30/1 has done already. If anything, the incumbent Government, of which SLFP President Maithiripala Sirisena is the head, may even be ruing the day that they acceded to co-sponsoring 30/1, if only out of spite for the Rajapaksa presidency locally more than out of commitment to the nation’s Tamils and the their international backers.

Independent of the ‘politics of missing-persons’, where the Tamil polity may once again indulging in mutual mud-slinging on what the TNA has done or not done, or what the latter’s ‘friends in Government’ have done or not done, there is the larger legal question. Should the courts decide favourably on Chithrangani’s petition and such others that may follow/accompany the same, the Government may have more than a huge problem on hand.

On the one hand, Governments, now and later, may find it extremely difficult to enumerate or track down the ‘missing persons’ of the JVP era than even those from the more recent LTTE era – and precisely for the same reason. Considering that the likes of Premkumar Gunaratnam could obtain ‘foreign citizenship’, and many more from the JVP era were believed to have done so, it is anybody’s guess if in a grown-up age, any or many of them would want to acknowledge their past, even in terms of original identities.

If it came to that, cooperation from the host-Governments in foreign lands in helping to identify Sri Lankans living under a ‘new identity’ may needs testing – just as it may be the case with the ‘missing persons’ from the LTTE era. The irony is that while they want Sri Lanka to render ‘justice’ to the families of the ‘missing Tamils’, the West did not even respond to the open appeals of the Rajapaksa-appointed Justice Paranagama Commission for help and cooperation in the matter, leave alone actually doing so.

All of it could well mean that Chithranganee’s petition has the inherent potential to blow up on the face of the Sri Lankan State, one way or the other. More importantly, it may also have a possible, unintended potential to de-rail the recently-appointed ‘Office of the Missing Persons’ (OMP) for missing Tamils from the LTTE era. The OMP flowed from international pressure and 30/1.

It is not without reason. After all, nothing in the nation can be seen to be offered to the Tamils if it had not already been offered to the majority Sinhalas. More specifically, whatever has been offered to the Sinhalas still cannot be offered to the Tamils or the other, Muslim ‘minorities’. Not certainly so when the nation is already on election-mode. Whichever election you mean, it is already upon the people, at least in their fertile imagination and politician’s prioritisation of the nation’s affairs!

http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=188417