Lowy Institute

An electoral failure might be a repudiation of the

military’s influence in politics – but not its irrelevance.

Myanmar’s main opposition party, the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), faces an uncertain political future after a dismal showing in this month’s general election, capped by its troubling refusal to recognise the results.

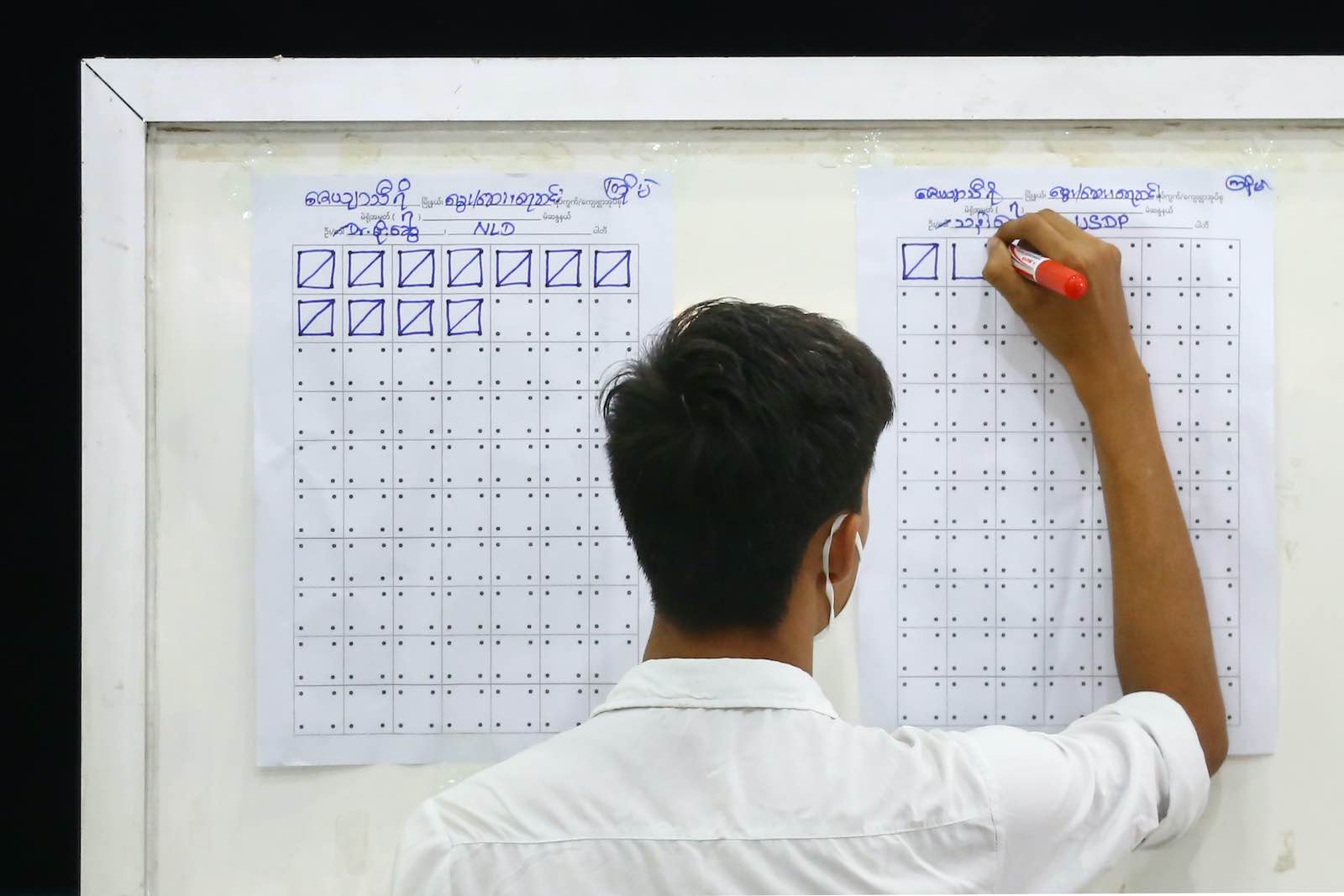

For the incumbent National League for Democracy (NLD), led by Aung San Suu Kyi, the margin of victory could hardly have been more emphatic. The NLD won 83% of elected seats (396 in total) in the national legislature – up from 79% in the 2015 poll. It also won a majority of elected seats in 12 of 14 subnational (or state and region) parliaments across the country.

With turnout high despite a worrying rise in Covid-19 cases, the vote was a strong affirmation of the widespread domestic support that the NLD (and Aung San Suu Kyi herself) continues to command.

By contrast, the USDP claimed only 33 seats (6.9% of elected seats) at the national level in 2020, eight fewer seats than in 2015. A string of senior USDP figures failed to win seats, including several former ministers, the party’s two vice-chairs and a former party chair. In four townships in southern Mandalay Region previously regarded as solid USDP territory, the party lost its seats to the NLD.

Rather than prompting any immediate soul-searching, the USDP leadership responded by canvassing spurious claims of electoral fraud and called for a new election to be held with the assistance of the military. These attempts to muddy the electoral waters took on an even more concerning edge amid isolated reports of post-election violence. In recent days, a newly elected NLD MP was shot dead by an unidentified gunman outside his home in northern Shan State.

While there were serious concerns about the organisation of the election, including questions over the impartiality of the election commission, the mass disenfranchisement of the Rohingya and the cancellation of voting in many conflict-affected areas of the country, election observers such as the Carter Center reported no major irregularities on voting day.

In crying foul, the USDP may have calculated that it would find a sympathetic ear with the military. Just prior to the election, in early November, commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing accused the election commission of “unacceptable mistakes” and cast doubt on whether the military would accept the results. However, after the poll, and perhaps in light of the decisive outcome, a spokesperson for Myanmar’s military, the Tatmadaw, stated that the USDP’s position was not supported by the army.

The military’s interests in parliament are already safeguarded, due to a constitutionally guaranteed bloc of 25% of seats in each chamber.

On the face of it, there is little reason for the Tatmadaw to publically throw their weight behind an unpopular political party. The military’s interests in parliament are already safeguarded, due to a constitutionally guaranteed bloc of 25% of seats in each chamber. The military also controls key security portfolios and will appoint one of two vice presidents.

The USDP was founded by the previous military junta to contest the 2010 general election – which the NLD boycotted – helmed by senior regime members such as Thein Sein and Shwe Mann. This association with the military remains, with former generals still common in the party’s ranks, despite vague commitments to support civilian candidates. In this election, the party won seats in several areas where Tatmadaw-backed militias hold sway.

Overall, the USDP’s electoral failure appears to represent a repudiation of the military’s influence in politics. However, it may be premature to predict the party’s total political irrelevance. For one, its military links also suggest access to powerful economic interests and resources that may shape its ongoing viability in ways not yet apparent.

The party also retains at least some base of support, the extent of which is not solely reflected in their overall seat tally under Myanmar’s first-past-the-post electoral system, but will be more evident in a final tally of their share of the popular vote. In the 2015 election, for example, the USDP won a sizable 28% of the popular vote, but only 8% of elected seats.

In the short-term, what political role the USDP plays when a new parliament convenes may partly rest with the NLD. After the 2015 vote, the NLD appointed several USDP members to political positions, including in cabinet – a move which caused internal fractures within the latter party.

In the wake of this year’s vote, while the NLD has reached out to a raft of ethnic political parties and spoken of a “national unity government”, it’s unclear whether the USDP will be offered a similar accommodation, especially given its ongoing refusal to accept the results.