Minorities languish in Indian jails and they are more likely to face the death penalty, according to a new report that analyzes official government statistics

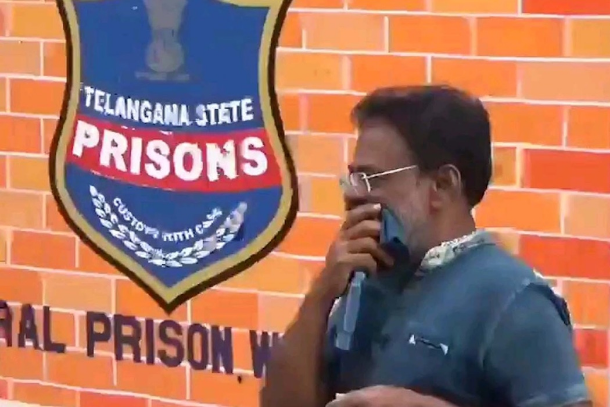

Tirunagaru Maruthi Rao, accused in the caste killing of a 24-year-old Dalit man named Pranay, outside a jail in the state of Telangana after a court granted him conditional bail on April 28. A report recently claimed that Indian police and the judiciary discriminate against Dalit and tribal people. (Photo IANS)

Umar Manzoor Shah, New Delhi India May 29, 2019

A disproportionate number of India’s minorities such as Muslims, tribal people and socially poor Dalits formerly known as ‘untouchables’ are imprisoned or sentenced to death.

This is a central finding of research carried out by the National Dalit Movement for Justice, the Centre for Dalit Rights and the Social Awareness Society for Youths (SASY).

A report on the investigation is to be presented to a session of the United Nations Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) in the first week of July.

The study quoted federal government data showing that by the end of 2015 India had 282,076 people incarcerated in various jails awaiting trial.

Of that number, at least 21 percent were Dalits, officially called ‘Scheduled Caste’, and 12 percent were tribal people, the report said.

Tribal people comprise only 8.2 percent of India’s population of 1.2 billion and Dalits make up 16 percent, according to the 2011 census.

That represents an over-representation of 33.33 percent for Dalits in relation to the number behind bars pending trial and and over-representation for tribal people in this situation of 51.22 percent.

There was a similar disproportionately high number of Dalits and tribal people on so-called ‘death row’ who were sentenced by courts to be executed.

By the end of 2017, India had 371 prisoners on death row with 279 of them, or 76 percent, belonging to socially poor classes and religious minorities such as Christians and Muslims.

All 12 female prisoners on death row were members of minority communities, the report said.

The research analysis found that the majority of Dalits, tribals and members of religious minorities imprisoned while awaiting trial, or on death row, were economically poor.

However, the report maintained that caste discrimination by officials arising from deeply entrenched prejudices was also a major factor in relation to harassment and incarceration.

“There are allegations that police officers have their own caste and gender biases and often behave in a discriminatory way,” the report stated.

It noted that Dalits and tribals facing trial were victims of India’s centralized justice system with a very low ratio of judges hailing from less well-off socio-economic groups as well as a dysfunctional and biased prison system.

Further, systemic bias was exacerbated by less representation of socially poor sections of society in police ranks.

The criminal justice system in effect worked “differently for different people” partly because of police mindsets.

“And it is not just our police, our entire criminal justice system operates with class, caste and religion further victimizing marginalized sections,” the report said.

Subhash Kumar, a Dalit rights’ activist, said there was clear evidence to back up the contention that the justice system is not fair to Dalits and other Indian minorities.

Indian independence from Britain after World War II did not in itself result in justice being delivered impartially.

Crimes committed against members of minority groups and discrimination against them remained of little concern to subsequent governments up until the present, Kumar said.

Hundreds of crimes are still committed against Dalit people on a daily basis.

Police recorded 422,799 crimes against Dalits in the ten years between 2006 and 2016, an average of 115 crimes a day.

During the same period, police recorded 81,332 crimes against tribal people.

Cases of crimes against Dalit people, in which investigations were not completed, rose from 8,380 in 2006 to 16,654 ten years later, the report said.

Regarding crimes against tribal people, the number of cases still to be investigated increased from 1,679 in 2006 to 2,602 in 2016.

According to Ish Gangania, a prominent social activist from New Delhi, criminal cases against members of the so-called upper castes reached the courts in large numbers, but those charged were often able to exert judicial or political influence.

There had been cases in the past two decades of upper caste individuals not being punished for instigating communal strife, such as anti-Sikh riots in 1984 and communal violence in Gujarat state in 2002.

Gangania said these examples demonstrated how “money, mafia, and muscle power” distort the dispensing of justice in India.

Sanjeev Kumar, a senior member of the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights (NCDHR), said the basic problem lies in the attitudes of many people.

“They consider Dalit people nothing less than filth, whose existence means little for the country,” he said,

Given Dalit and tribal contributions to the nation’s development, it was ironic how often they were socially ostracized, Kumar told ucanews.com.

Dalit is a common name given to the socially oppressed former “untouchables” outside India’s four-tier caste system.

They engaged mainly in menial work and even being in close proximity to them was shunned by many members of higher castes.

Although untouchability and caste discrimination were banned by law in India, entrenched social prejudices are enduring.